A recent genetic study led by Italian researchers has found that people who live past 100 (known as centenarians) share a higher amount of DNA inherited from Western Hunter-Gatherers, Ice Age populations that lived in Europe long before farming took hold. This ancient genetic fingerprint, found more frequently in the DNA of super-aged Italians, may influence how the body responds to stress, infection, and aging.

The research, led by Prof. Cristina Giuliani of the University of Bologna, analyzed DNA from over 1,000 individuals and discovered that centenarians had significantly more genetic variants linked to hunter-gatherer ancestry than their younger counterparts. The team focused specifically on a distinct genetic cluster known as Villabruna, dating back around 14,000 years, which still echoes in modern genomes.

Italy, sitting at a historical crossroads of human migration, offers a rare genetic mosaic, one that helps make this kind of longevity research possible. According to national data, over 23,000 people aged 100 and older were living in Italy as of January 1, 2025, with a striking 83% being women. This demographic richness allows scientists to ask a fascinating question: could DNA from prehistoric populations be quietly shaping how we age today?

Ancient DNA Reveals Survival-Linked Traits in Modern Genomes

The study compared 333 centenarians with 690 younger adults from similar geographic regions. The results consistently showed a stronger presence of Western Hunter-Gatherer DNA in the older group. According to Giuliani, the findings highlight how “ancient genetic components” still influence complex traits such as longevity.

In the DNA of the longest-lived individuals, researchers found clusters of genetic variants tied to immune response and cellular repair. These changes likely helped Ice Age bodies survive harsh winters and food shortages, conditions that may have favored robust stress regulation and strong immunity. The idea is not that any one gene ensures a longer life, but that patterns across the genome, shaped by ancient selection, still have measurable effects today.

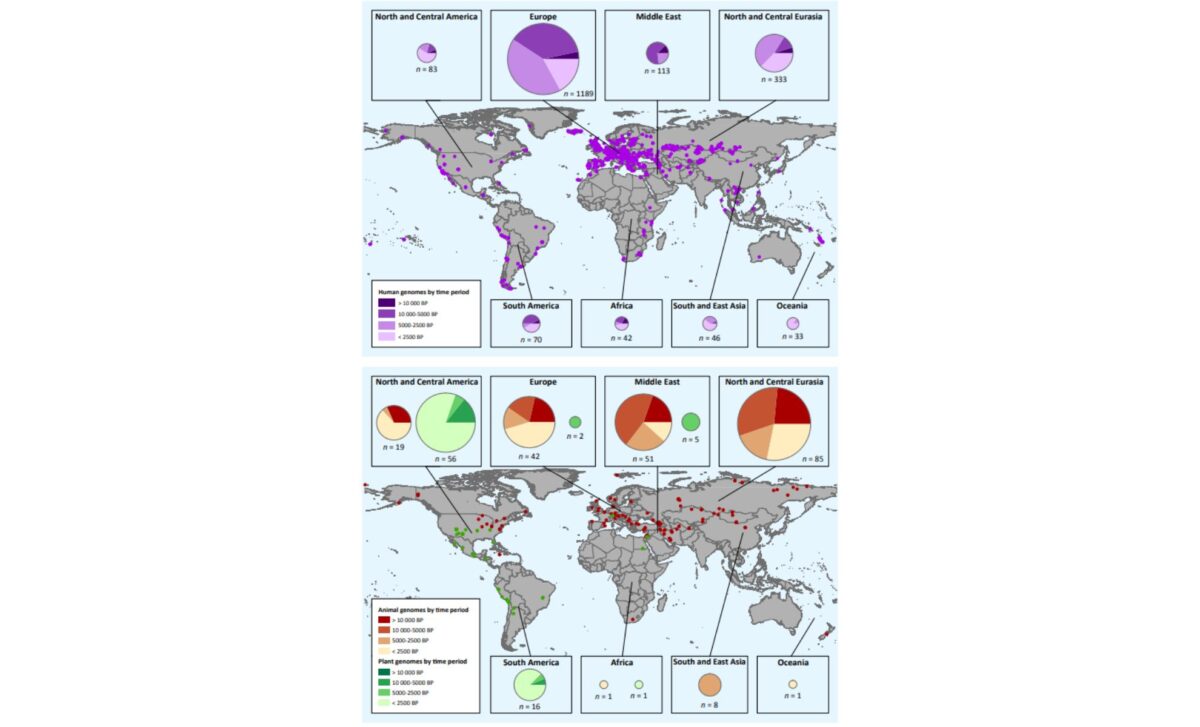

Through paleogenomic comparisons using 103 ancient DNA samples, the study modeled modern participants as a blend of four ancestral components: Neolithic farmers, steppe herders, Iranian-Caucasus groups, and Western Hunter-Gatherers. It was the last group that stood out, with its unique variants appearing more often in those who lived to extreme ages.

Women Carry the Signal More Clearly

Among the centenarians studied, women displayed the clearest link between ancient ancestry and long life. According to official figures cited in the report, of the 724 Italians aged 105 or more in early 2025, over 90% were women. And while the genetic effect was harder to confirm in men (partly due to smaller sample sizes) it raises the possibility that sex-linked biology and history both play a role.

Women in prehistoric times may have faced different survival pressures, possibly leading to different biological adaptations. These adaptations, preserved in mitochondrial DNA or other inherited variants, could still shape how women’s bodies handle aging, disease, and inflammation today.

The gender gap is also visible in Italy’s longevity records. As reported by national statistics, the country’s current decana, or oldest living woman, is set to turn 115 this year in Campania. In contrast, the oldest man, a resident of Basilicata, has reached 111. While environmental factors and lifestyle surely matter, genetics appear to be part of the equation too.

Hunter-Gatherer Genes and the Biology of Aging

What makes Western Hunter-Gatherer DNA so interesting is not just its age, but the biological functions it may influence. Scientists know that aging is often accompanied by a rise in chronic inflammation, a phenomenon known as inflammaging. This slow-burning immune response has been linked to a higher risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and neurodegeneration.

In centenarians with higher hunter-gatherer ancestry, Giuliani’s team found genetic variants in regions associated with immune modulation and metabolic balance. These could potentially slow down inflammaging, though the study stops short of claiming a direct effect. Only lab experiments can confirm whether these ancient variants still affect gene expression today.

According to the ancestry study, the odds of living past 100 were about 38% higher for individuals with a stronger Western Hunter-Gatherer genetic profile. That said, the researchers also stress the importance of context, factors like childhood environment, pollution, and access to healthcare may confound the results.

Still, the idea that modern aging could be shaped by Ice Age survival strategies is a striking reminder of how deeply our biology is tied to the past. Paleogenomics, by linking ancient genomes to present-day health traits, continues to offer new insights, not only about who we were, but how we live now.