Content warning: This story contains descriptions of domestic violence and abuse. If you or someone you know needs help, contact the Illinois Domestic Violence Hotline at 877-863-6338.

CHICAGO — It was the first day of a new year and the last day of Martina Mosby’s life.

Mosby, 43, was ringing in 2025 with her 18-year-old daughter and her longtime boyfriend Reginald Freeman in their North Lawndale home when she and Freeman began arguing. Mosby’s daughter stood between them and tried to break up the argument, but tensions escalated. Freeman then shot Mosby several times, and after she fell to the ground, he shot her again several more times, police said. Investigators recovered 11 shell casings from the scene, according to prosecutors.

Mosby, a home care nurse and mother of three, was taken to the hospital, where she died from her wounds. Freeman was charged with first-degree murder and is now awaiting trial. He has pleaded not guilty.

“I know I’m not supposed to hate people, but I think I hate [Freeman] because he took my best friend from me,” Mosby’s longtime friend Val Stevens told Block Club Chicago through tears.

Mosby was the first of at least 63 Chicagoans killed in a domestic homicide in 2025.

(from left) Val Stevens and Martina Mosby were practically inseparable growing up together in Chicago Lawn. Stevens said she and Mosby even dressed alike and dated some of the same boys: “When you seen Val, you seen Tina,” she said. Stevens said they remained close for years and only drifted apart as Mosby’s relationship developed with her longtime boyfriend, Reginald Freeman. Credit: Provided

(from left) Val Stevens and Martina Mosby were practically inseparable growing up together in Chicago Lawn. Stevens said she and Mosby even dressed alike and dated some of the same boys: “When you seen Val, you seen Tina,” she said. Stevens said they remained close for years and only drifted apart as Mosby’s relationship developed with her longtime boyfriend, Reginald Freeman. Credit: Provided

While homicide totals and most other violent crime figures dropped in Chicago last year, homicides that resulted from domestic violence increased by 15 percent, according to the city’s violence reduction dashboard.

The dashboard tallied 52 domestic violence homicides in 2025, which doesn’t count 11 people included in police data Block Club obtained through a public records request. The dashboard, run by the Mayor’s Office, categorizes domestic crimes differently than the Chicago Police Department. Dashboard data also shows domestic fatal shootings alone spiked by more than 50 percent, the highest single-year increase since 2020.

In addition, a “record-breaking” number of calls were made to the Illinois Domestic Violence hotline last year, according to Madeleine Behr with The Network: Advocating Against Domestic Violence, a coalition of local organizations. The Network will release exact figures in a report this spring.

Advocates say the surge in violent abuse is due to “a tornado of risk factors,” including longstanding issues exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath, such as unstable employment, food insecurity and homelessness.

At the same time the need for services has increased, many community organizations and nonprofits are facing budget cuts and restricted federal funds. Some have had to stop accepting new clients because wait lists are too long, Behr said.

Tessa Kuipers, program director and policy advisor for Family Rescue, a South Side-based community service provider, described the current climate as “helpless.”

“‘Helpless’ is a really sad word to use, but it has felt like there’s just a level of services and resources that we haven’t really been able to provide the way we want to,” Kuipers said.

“To see people in really severe danger, and then not being able to meet their needs and their resources. … It has felt very hopeless and frantic.”

‘Strained’ Resources For Survivors

Alex Hernandez, site coordinator at Family Rescue, grew up witnessing domestic abuse in her East Side household “very, very often,” which ultimately motivated her to work in domestic violence advocacy.

Finding stable housing is one of the ways Hernandez and other advocates try to help survivors get out of abusive situations. But Hernandez said she’s found that, in recent years, matching survivors with emergency housing has been “next to impossible.”

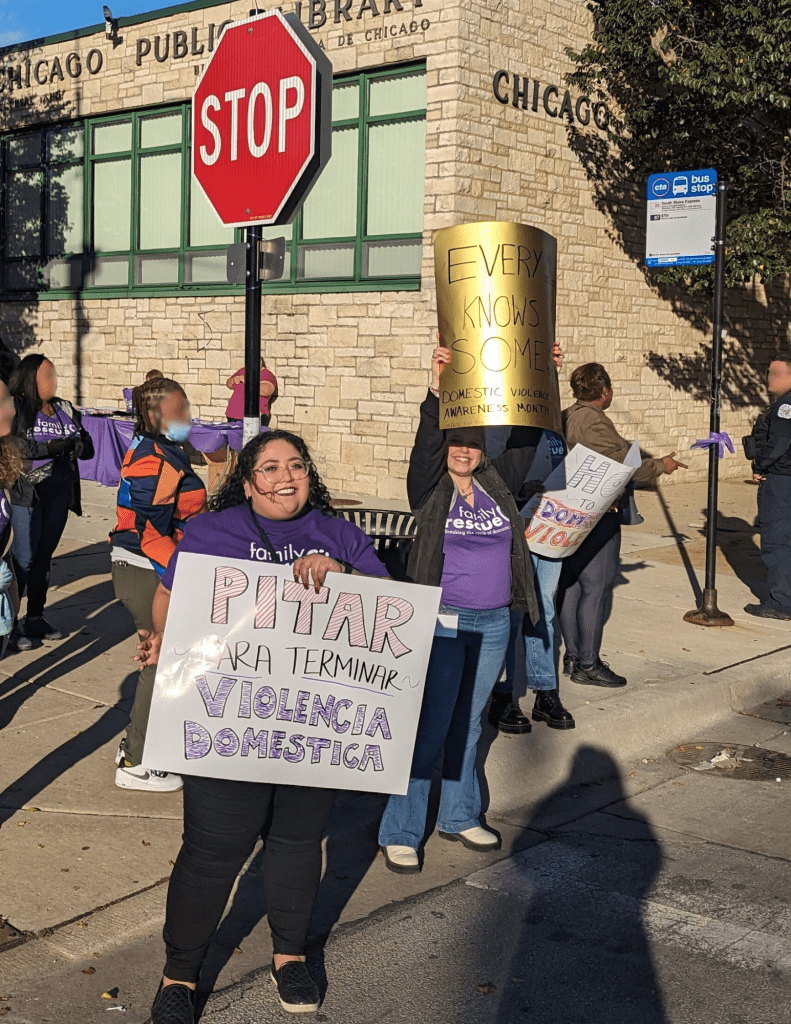

Family Rescue advocates Alex Hernandez (left) and Kara Bryant at a domestic violence awareness event in October 2023. Credit: Courtesy of Family Rescue

Family Rescue advocates Alex Hernandez (left) and Kara Bryant at a domestic violence awareness event in October 2023. Credit: Courtesy of Family Rescue

One mother enduring domestic violence recently turned to Family Rescue after she lost her job and couldn’t make rent. Case managers tried to connect the woman with court-based rental assistance and legal aid, but she was denied, in part because the program didn’t have capacity. Now the woman and her children are facing eviction, according to Kuipers.

Generally, when they’re denied services, survivors become more reliant on their abusers for shelter and other immediate needs like food and medical care, increasing their risk of further abuse, advocates said.

“There’s not enough shelter beds. When you have a survivor who has four children and one is a toddler or an infant … I’m not looking for one bed, I’m looking for five beds and a crib,” Hernandez said.

In many situations, relocating would make a survivor safer but “you just can’t do it because [the shelter and low-income housing system] doesn’t move fast enough,” she said.

Last year, more than 80 percent of domestic homicides happened on the South and West sides, according to police data that includes domestic homicides through Dec. 11. The records show the victims were a mix of men and women, the majority of them Black.

Chicago has long struggled with elevated gun violence, which has led to significant financial investment in violence prevention. In 2024, city and state officials reached a fundraising milestone, allocating $100 million to community violence intervention with the goal of reducing shootings and homicides by 75 percent over the next decade.

But advocates say not enough funding and attention has gone specifically to domestic violence prevention, which may be one reason why homicides have increased.

Adapting To Serve Those Left Behind

Domestic homicides involve people who know each other, sometimes intimately. Perpetrators often attack or shoot at a shorter range, increasing the likelihood of fatal injuries, Behr said.

Mosby and Freeman dated for more than a decade. As the years went on, Mosby became more secretive and even refused to share their home address with her closest friends, Stevens said. Eventually, Mosby only spent time with Freeman.

(from left) Martina Mosby and Val Stevens were friends since childhood. Stevens was crushed when she learned Mosby had been killed, allegedly by her longtime boyfriend, last January. Credit: Courtesy of Val Stevens

(from left) Martina Mosby and Val Stevens were friends since childhood. Stevens was crushed when she learned Mosby had been killed, allegedly by her longtime boyfriend, last January. Credit: Courtesy of Val Stevens

“Not being able to tell her address isn’t Tina. That definitely wasn’t her, especially when it came to me,” Stevens said. The two had grown up together on the South Side and were so close that people referred to them as the “Doublemint twins.”

In an emailed statement, Matthew Hendrickson, spokesperson for the Cook County Public Defender’s Office, said Freeman pleaded not guilty to charges, “which are only allegations and have not been proven in a court of law.”

In lieu of investment in preventative resources, many survivors turn to the legal system for help. Still, according to police data, many domestic homicides went unsolved last year. In eight of the 63 domestic homicides recorded through mid-December, police said they identified the killers, but prosecutors didn’t approve charges. And in the remaining 55 cases, 45 percent were unsolved as of mid-December.

Family Rescue helps run a multi-disciplinary program dedicated to identifying high-risk survivors — people who are at greater risk of getting injured or killed by their abusers. The program is a partnership between several community organizations and city agencies, including the Chicago Police Department and the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office.

Through the program, which launched back in 2014, police officers give survivors a domestic violence assessment at the scene of an incident. That report is then shared with Family Rescue and other community organizations for further evaluation.

Tessa Kuipers speaks outside the Circuit Court of Cook County, 555 W. Harrison St. on the Near West Side, on Sept. 3, 2025. Credit: Colin Boyle/Block Club Chicago

Tessa Kuipers speaks outside the Circuit Court of Cook County, 555 W. Harrison St. on the Near West Side, on Sept. 3, 2025. Credit: Colin Boyle/Block Club Chicago

On average, those “risk scores” have been markedly higher the past few years, Kuipers said.

Yet community organizations can’t keep up with the overwhelming demand for services, advocates said. Some have shifted focus to help serve those left behind after a domestic homicide.

Life Span, a local nonprofit, has for decades provided legal representation and court advocacy to survivors and victims of domestic violence, sexual assault and human trafficking across Cook County.

But last year, with domestic fatal shootings on the rise, the organization began regularly offering an additional set of legal services: guardianship and power-of-attorney authorization. The effort started with a guardianship case in 2024, when an elementary-age child was left alone after their mother was killed in a domestic attack and their father was incarcerated pending trial for murder.

These legal arrangements help survivors establish caregivers who can make personal or financial decisions for their children or themselves if they die or are incapacitated.

Life Span went on to handle more than 100 guardianship and power-of-attorney cases last year, a massive increase from previous years when the organization handled roughly 15 cases a year, said Amy Fox, the organization’s executive director.

“No one wants to think about the fact that your abuser might murder you, but it is a real truth, and you can be prepared for it,” Fox said.

The large increase was also driven significantly by Life Span’s efforts to help immigrant domestic violence survivors and their families in the event that someone in the family is arrested or deported during the federal immigration roundups, Fox said.

Federal Funding Woes

Even as advocacy organizations aim to adapt to the increased need, they fear resources may become even harder to come by, as the Trump administration continues to target Illinois with federal cuts to essential services. The administration recently tried to freeze about $1 billion for child care and social services in the state, but the move was temporarily blocked by a federal judge.

Mayor Brandon Johnson’s initial budget slashed city funding for gender-based violence services by more than 40 percent. But after fierce pushback from organization leaders and survivors, Johnson put forth a proposal that restored $9 million in funding for gender-based violence services such as rapid re-housing and counseling. That was part of the final budget passed by the City Council last month.

In an interview with Block Club, Johnson said he “fought hard” to replenish the city funding and supports making “ongoing” investments to shelters and other community organizations that provide services to survivors.

Yet many nonprofits across Cook County have seen their budgets slashed due to cuts to federal grant programs during the Trump presidency.

Mayor Brandon Johnson delivers his 2026 budget address to City Council on Oct. 16, 2025.

Mayor Brandon Johnson delivers his 2026 budget address to City Council on Oct. 16, 2025.

Resilience, a rape and sexual assault crisis center, had to terminate six full-time positions after losing half a million dollars from the Victims of Crime Act (VOCA) program, organization leader Sarah Layden told Block Club in September. Funding for the federal program, supported by fines and penalties collected through federal criminal cases, is at an all-time low, in part because the Justice Department is reaching more settlements.

Many other organizations are bracing themselves for additional funding restrictions under the Trump administration.

Family Rescue runs a 36-bed shelter that is funded by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Kuipers said the federal government has threatened to change funding requirements for such projects, which has left them in a financially precarious position until the department releases its final budget in the spring.

Meanwhile, incidents of domestic violence haven’t slowed, advocates said.

Stevens herself escaped domestic violence a few years ago. She left the relationship after getting therapy at Family Rescue.

“I was so close to wanting to go back, but I was going to those meetings, I kept firm and strong, and I didn’t go back to this particular situation. It very much helped me,” she said.

Stevens said she wishes her friend had done the same.

This Story Was Produced By The Watch

Block Club’s investigations have changed laws, led to criminal federal investigations and held the powerful accountable. Email tips to The Watch at investigations@blockclubchi.org and subscribe or donate to support this work.