US scientists have debunked a 70-year-old physics law that has long guided how engineers make metals stronger, after they found out that materials behave very differently when struck at supersonic speeds.

The research team at New York’s Cornell University found that reducing a metal’s grain size, a long-taught method for increasing strength, can instead cause the material to soften when deformed at extreme speeds.

Their finding contradicts the Hall–Petch law, which predicts that metals become stronger as their internal grain size decreases. Under this model, grain boundaries act as barriers to dislocations, the microscopic defects that drive deformation.

“We wanted to test the limits of that rule and see whether grain boundary strengthening still holds when metals are pushed into truly extreme deformation rates,” Mostafa Hassani, PhD, an assistant professor at the Sibley School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering (MAE), said.

Breaking the laws of physics

Hassani, who teaches in Cornell University’s Department of Materials Science and Engineering, and Laura Wu, a PhD student, both co-authors of the study, set out to examine how metals behave under extreme, ultra-fast deformation.

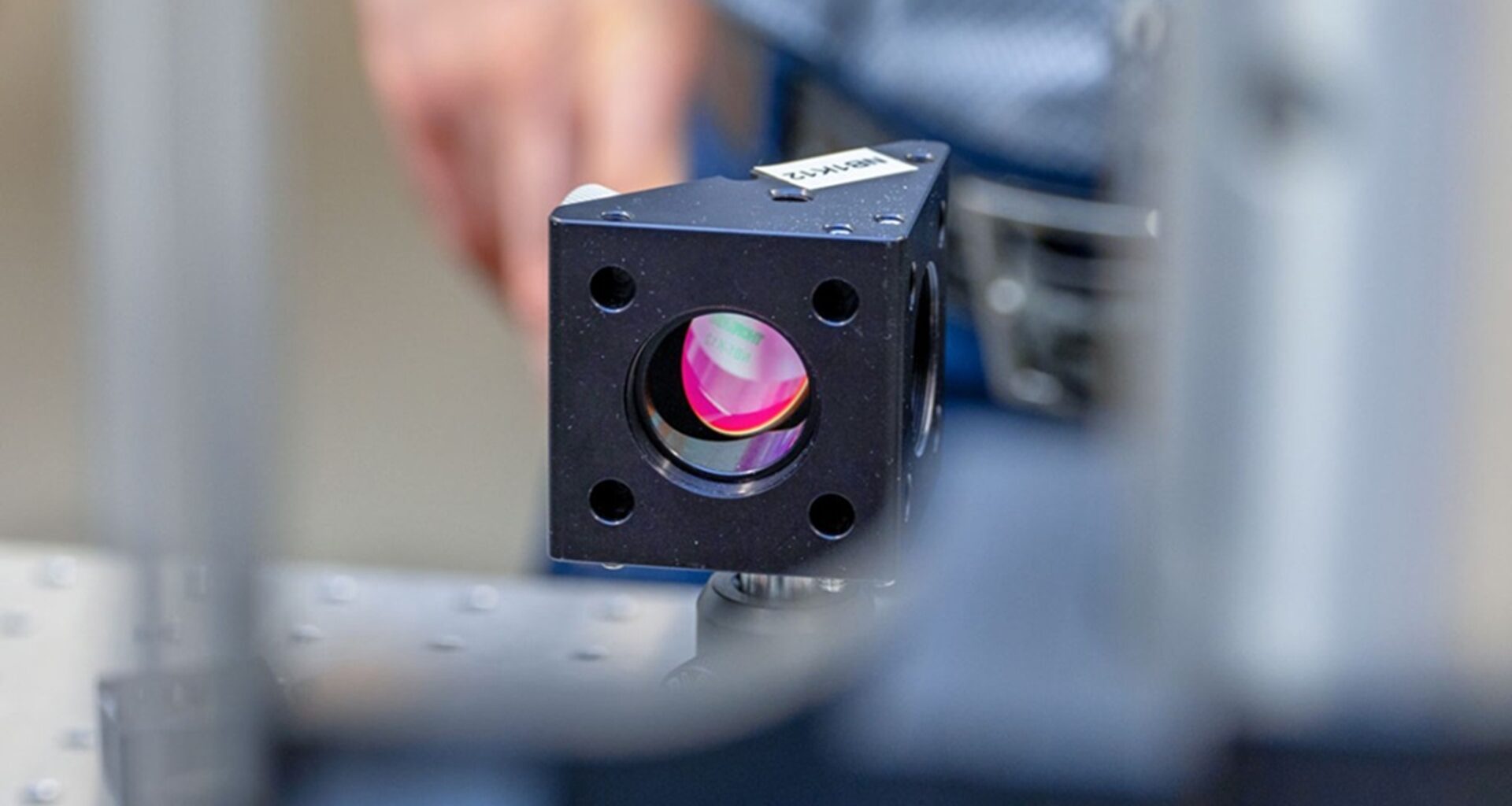

To do so, they used laser-induced microprojectile impact testing, a technique that fires microscopic particles at metal targets at velocities that exceed the speed of sound, or about 761 miles per hour (mph).

“It had been difficult to study these ultra-high strain rates until recent technical developments enabled us to carry out these experiments,” Wu reported. “These tests are uncovering new understandings of how, exactly, materials can behave.”

Mostafa Hassani, PhD, an assistant professor at Cornell University (right).

Mostafa Hassani, PhD, an assistant professor at Cornell University (right).

Credit: Charissa King-O’Brien / Cornell University

But what the researchers thought was going to be a straightforward confirmation experiment turned out to be something totally unexpected. “We double-checked all our data collection,” Wu added. “We added new data points and repeated experiments, but the results held every time.”

For the research project, they prepared copper samples with grain sizes varying from one to 100 micrometers, a range in which the Hall-Petch effect is typically expected to hold.

During impact tests, samples with larger grains continuously showed shallower indentations. These were both indicators of greater hardness and higher energy dissipation in the copper. The result defied decades of scientific understanding.

Strength theory challenged

The researchers noted that the Hall-Petch effect has dominated materials science for more than 70 years. The rule states that smaller grains, or microscopic crystal regions inside a metal, block the movement of defects known as dislocations.

This makes the material harder and more resistant to deformation. The principle underpins everything from aircraft design to protective armor. The research team attributed their results to how tiny defects, known as dislocations, move when a metal deforms.

According to the team, at ordinary strain rates, grain boundaries and other crystal defects strengthen a metal by blocking the motion of these dislocations. But at ultra-high strain rates, dislocations accelerate fast enough to start interacting with the material’s vibrating atoms.

The interaction, called dislocation–phonon drag, can greatly strengthen the metal. Although the experiments focused on copper, the team believes that the effect is universal. Early tests on other metals and alloys found similar reversals in strength behavior when deformation rates become extreme.

“For me, the exciting part is both the fundamental discovery and the potential applications,” Wu concluded in a press release. “Now that we know the grain-size trend reverses at a high-strain rate, we can use this to build and improve things that withstand high impacts.”

According to the researchers, the new insights could influence the development of materials for applications like lightweight armor, additive manufacturing of metal components and spacecraft that survive collisions with space debris.

The study has been published in the journal Physical Review Letters.