In a few years, it will be so easy. When Clayton Kershaw appears on a Hall of Fame ballot, every voter with a functioning brain will check the box beside his name. Same with Max Scherzer and Justin Verlander.

All of those pitchers won three Cy Young Awards, 200 games and multiple World Series championships. They all struck out 3,000 hitters and made at least eight All-Star teams. Their Cooperstown cases will not hinge on the context of their era or a complex statistical formula. You don’t even have to think about it.

Some writers vote that way – If I have to think about him, he’s not a Hall of Famer – and that is their right. But most believe that each candidate deserves rigorous study. There are 279 players in the Hall of Fame, and when building a case, well, all the pieces matter.

On Tuesday, when the Hall of Fame announces the results of this year’s writers’ ballot, no starting pitcher will collect the necessary 75 percent for election. There are six starters under consideration, and the three returning candidates — Mark Buehrle, Felix Hernández and Andy Pettitte — did not combine for even 60 percent last year. And none of the three newcomers — Gio González, Cole Hamels and Rick Porcello — are obvious choices.

González and Porcello made the ballot as a way to acknowledge very good careers. They have gotten no votes among the 174 public ballots compiled by Ryan Thibodaux’s Hall of Fame tracker.

This is Buehrle’s sixth ballot, and he is polling at 23.5 percent. His durability would not compute in the modern game — 14 consecutive seasons with 200 innings! — but Buehrle was just short of dominant. He appeared on Cy Young ballots only once, in 2005, when he finished fifth.

Pettitte, a postseason titan who was 103 games over .500, at 256-153, is gaining momentum in his eighth appearance. Twenty-eight voters who rejected him last year have since changed their minds, bumping Pettitte to 57.4 percent in the public balloting.

But percentages tend to dip upon full reveal, and Pettitte — who admitted to using human growth hormone to recover from injuries in 2002 and 2004 — has never registered more than 27.9 percent. He’ll have two more tries before exhausting his eligibility on the writers’ ballot.

Which brings us to Hamels and Hernández, a pair who personify the Pam Beesly meme: They’re the same pitcher. Both logged 15 seasons with almost identical results: 422 starts, 163 wins and a 3.43 ERA for Hamels, 418 starts, 169 wins and a 3.42 ERA for Hernández. Hamels had 36 more strikeouts and 38 fewer walks.

The bonus material is a little different. The left-handed Hamels won an NLCS and World Series MVP award for the Philadelphia Phillies, but never placed in the top three in Cy Young award voting. The right-handed Hernández never appeared in the postseason as a career Seattle Mariner, but won a Cy Young and was runner-up twice.

In any case, Hamels and Hernández stand as a bridge between eras when expectations changed. In 2005, when Hernández broke in, 50 pitchers worked at least 200 innings. In 2019 — the final full season for both — only 15 did so. Last season, that number dwindled to three. (Take a bow, Logan Webb, Garrett Crochet and Cristopher Sánchez).

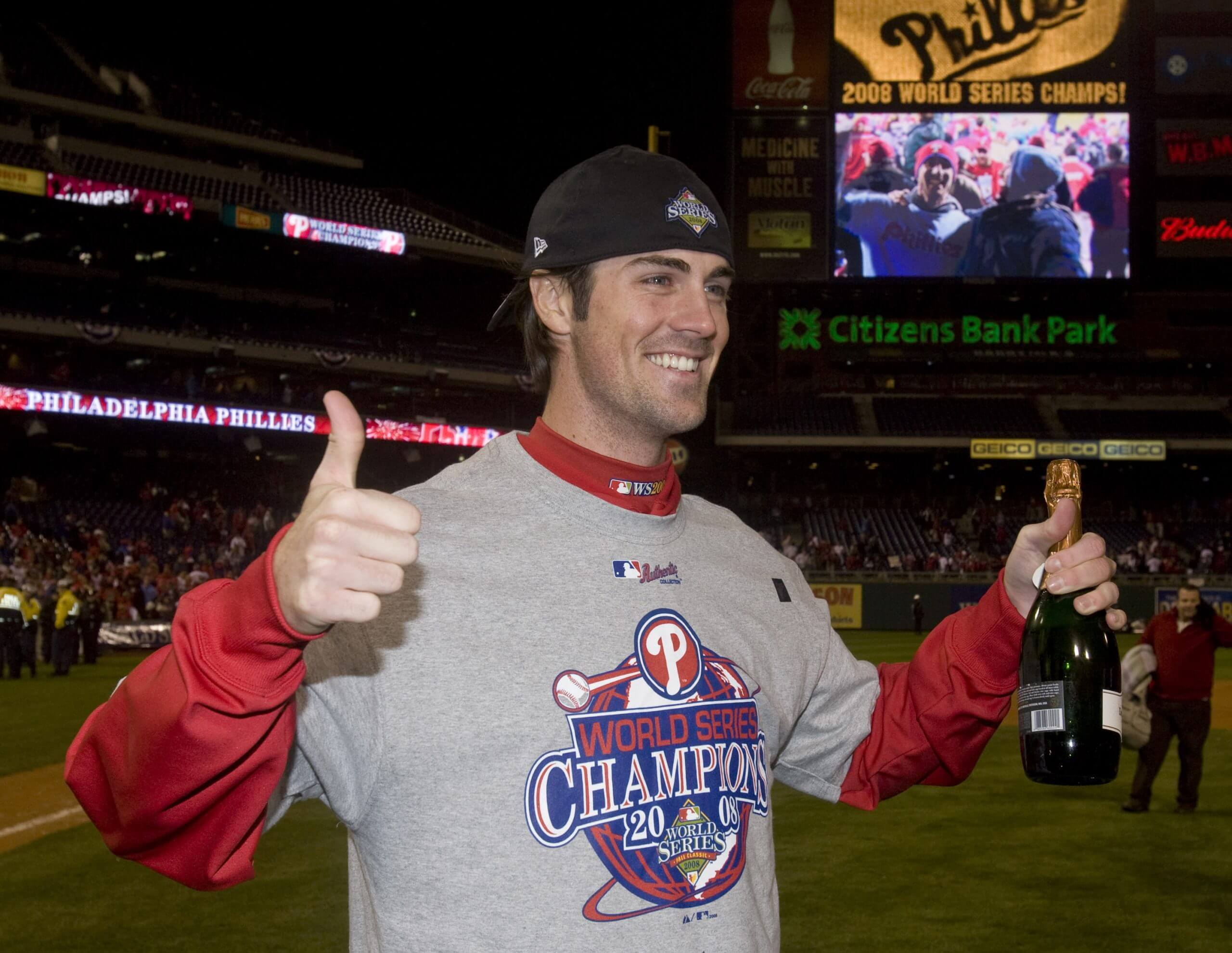

World Series MVP Cole Hamels celebrates after winning the 2008 title in Philadelphia. (Chris O’Meara / Associated Press)

A useful metric to compare pitchers across time is ERA+, which accounts for ballparks and scoring environments. The all-time leaderboard is a mix of modern and classic eras, starters and relievers; the 6-7-8 spots belong to Jacob deGrom, who is active; Jim Devlin, who died in 1883; and Satchel Paige, who played in the Negro Leagues and the American League.

Hamels’ ERA+ is 123, and Hernández’s is 117, meaning they were theoretically 23 and 17 percent better than the league average. But that alone doesn’t tell us much, since dozens of starters reside in the 117-to-123 neighborhood. Some from this century are in, like Tom Glavine and Mike Mussina, and some are not, like Cliff Lee and Carlos Zambrano.

The question for voters — and especially beyond the candidacies of Kershaw, Scherzer, Verlander and Zack Greinke — is how to define a new standard for Hall of Fame starters. Hamels and Hernández were relative workhorses; both logged eight seasons of 200 innings and finished with around 2,700 apiece. But even that falls below the established Hall baseline.

Only three AL/NL starters in the last century have reached Cooperstown with fewer innings than Hernández, who worked 2,729 2/3 — Sandy Koufax, Lefty Gomez and Dizzy Dean. Sooner or later, that will have to change. Because if Hernández’s resume seems light, consider that no active starter under 35 is within 1,000 innings of his total.

That doesn’t mean Hernández or Hamels should start preparing an acceptance speech. Historically, they may belong more to a group of exceptional starters a tick below Cooperstown: Ron Guidry, Tim Hudson, Jerry Koosman, Billy Pierce, Bret Saberhagen and so on.

There would be no shame in that. But in time, as workloads continue to shrink, recent excellence and relative longevity will look better and better. That is why great players get a decade on the ballot: Their statistics never change, but perspectives sometimes do.