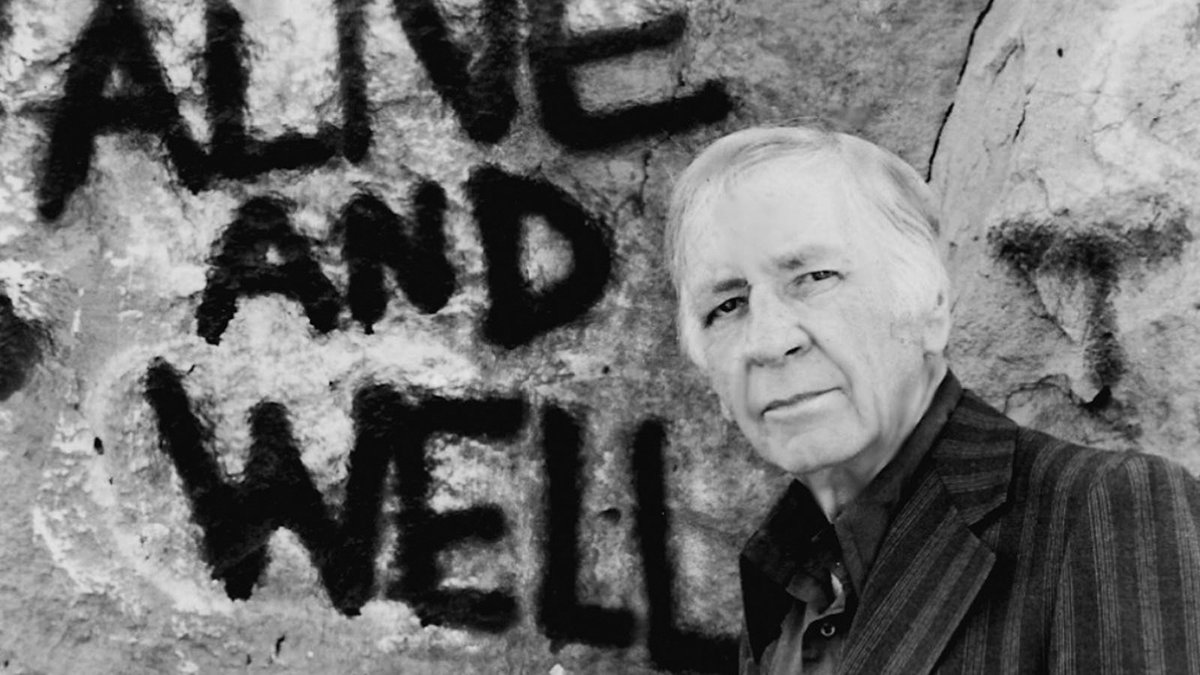

From liquor- and dope-peddling bellhop-turned-hustler (during Prohibition, yet) at Fort Worth’s historic Hotel Texas, to off-brand pulp-fiction author of unexpected literary immensity, Jim Thompson forged a career like few others in crime fiction: He might as well have been one of his own misbegotten characters. His legacy has found him popularly regarded as a “dime-store Dostoevsky,” as the critic Geoffrey O’Brien has termed the tormented author.

In a biographical study called Difficult Lives (Gryphon Books, 1993), the novelist James Sallis emphasizes O’Brien’s likening of Thompson to Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821-1881), the influential and provocative Russian author.

Parallels are self-evident in the respective writers’ courtship of controversy; in their touches of autobiography in their more problematic fictional personalities; and in their confrontational approaches to social criticism.

Both lived as outsiders, popular recognition notwithstanding. Dostoevsky toiled in a higher literary realm, though hounded by repression and legal woes. Thompson courted the bottom-feeder market of pulp magazines and original paperback novels — lurid emotionalism and impulsive violence, yielding fevered reading at 15 cents or a quarter per copy. Both wrote fearlessly, although Dostoevsky would have cringed from the undignified pulp-thriller marketplace of the mid-20th century. Thompson approached the arena subversively.

Thompson wallowed in a deceptive mire of cheap sensations and disposable anti-literature, with a detox-and-retox cycle of alcoholism as a chronic muse. His ideas were bigger than his medium: Filmmaker Stephen Frears, who adapted Thompson’s 1963 novel The Grifters in 1990, has hailed the elements of Greek tragedy in the books.

James Myers “Jim” Thompson (1906-1977) wrote more than 30 hard-boiled crime novels, mostly paperback originals, from the late 1940s through the middle 1950s. Sporadic critical nods aside, Thompson was seldom recognized as a literary figure during his lifetime. Only after his death did his stature grow.

His more memorable works include The Killer Inside Me, Savage Night, A Hell of a Woman and Pop. 1280. These titles find Thompson transforming the crime genre into a medium of challenge, with erratic narrators, dreamlike narrative structures, and the erratic impulses of dying or deranged characters. Such more dignified authors as Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, and Horace McCoy never attained the raw-nerve extremes of Thompson. In an introduction to a modern-day edition of the bleak, near-autobiographical Now and on Earth (a début novel from 1942), Stephen King characterized Thompson as “absolutely over the top … didn’t know the meaning of the word ‘stop.’”

Thompson praised his father, lawman-turned-oilman James “Big Jim” Thompson, in such books as Bad Boy and King Blood — after having reviled the man (by proxy) with near-pathological anger in The Killer Inside Me.

Born in Anadarko, Oklahoma — his sheriff-father fled for Mexico after an accusation of embezzlement — Jim Thompson found his family reunited by 1910. The Thompsons resettled in Fort Worth. Jim began writing in earnest as a schoolboy but made his earliest popular impression as a Hotel Texas bellboy capable of supplying drugs and liquor for guests intent upon bending the law. He claimed earnings of $300 a week, in addition to his official $15 a month.

Thompson’s own indulgences left him an alcoholic at 19, with a nervous collapse to show for it. While working at age 26 as an oilfield laborer, he joined his father in a drilling operation that went from boom-to-bust in a few years. Thompson renewed his literary momentum in Fort Worth, then enrolled in the University of Nebraska — only to drop out in 1931. He researched criminal cases for true-crime magazines, not as a journalist but rather as a sensationalist, imposing a first-person narrative voice as if from direct observation.

Popular recognition eluded him, and by now Thompson had a family to support. He entered the low-prestige but better-paying genre of crime fiction with a novel called Nothing More than Murder. Lion Books, a small-time paperback publisher, offered creative freedom in exchange for Thompson’s ability to make a typewriter smoke. Thompson became a reporter with the Los Angeles Mirror during 1948-1949 — just long enough for his novels to develop momentum.

A breakthrough with The Killer Inside Me (1952; twice filmed, in 1976 and 2010) encouraged a pace of five novels a year during 1953-1954. In keeping with the homicidal protagonist of The Killer Inside Me, 1953’s Savage Night introduced a hired gunman, foredoomed by disease, whose parallel mental collapse triggers a surreal ending. Such an experimental approach is unusual in a paperback designed to be read once and then discarded.

A hitch with screen director Stanley Kubrick found Thompson assigned to adapt a Lionel White novel, Clean Break. Kubrick called the film “The Killing” (1955) and claimed screenplay credit, acknowledging Thompson for additional dialogue. Kubrick and Thompson would collaborate again, on “Paths of Glory” (with Calder Willingham) and on an abortive effort called “Lunatic at Large,” which collapsed after Kubrick moved into epic-scale assignments with “Spartacus.”

From the mid-1950s through the 1960s, Thompson completed one novel a year. The paperback field was dwindling, overshadowed by television. Thompson ditched the crime-thriller books but persisted with a sideline in scripts for such television serials as “Mackenzie’s Raiders” and “Convoy.”

Thompson’s most formidable novel of the waning 1950s, The Getaway, would become a filmmaking project for Sam Peckinpah, though compromised by interference from star player Steve McQueen, who demanded thrilling action over Thompson’s provocative dialogue. Meanwhile, Thompson’s more obscure novels were finding acclaim among the French literati, pointing toward a mass-market rediscovery in America.

And why the recurring interest in an author who summoned miserable fringe-dwellers and dwelt on the inner workings of their warped minds? What’s with the attention to a chronic drunkard who plotted his yarns as if literalizing the 3-D delirium tremens into sentences and paragraphs?

Thompson avoided good-guy characterizations, for the most part, and the occasional impulse of common decency is scarcely a match for rampant opportunism and fraudulence. The redeeming quality is the opportunity to follow a daring literary experimentalist/extremist as he challenges the rules of narrative fiction — sometimes sloppy, as if in haste to get everything down before the thought dissipates, and often willing to test the reader’s patience by blurring the lines between imagination and reality. Jim Thompson wrote as he lived, without a safety net of restraint, and don’t try this at home.