A steady aerobic routine might do more than boost your mood and stamina. New findings suggest it can nudge your brain’s biology in a younger direction, at least as measured by brain scans.

Over 12 months, adults who stuck with regular cardio ended the year with brains that looked almost a year “younger” than those who kept their usual activity levels.

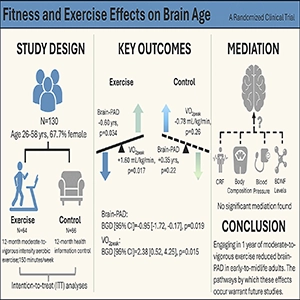

The research, led by the AdventHealth Research Institute, focused on “brain age” – an MRI-based estimate of how old a brain appears relative to a person’s actual age.

A higher brain-predicted age difference, or brain-PAD, signals a brain that looks older than expected.

Previous studies have linked higher brain-PAD to worse physical and cognitive outcomes and a higher risk of death.

Measuring the brain’s age

Many brain health studies rely on tests of memory or attention, or they wait for clear clinical changes to appear.

This study leaned on imaging and asked a different question: can lifestyle shift an early biological marker before problems show up?

The researchers used MRI scans to estimate brain age at the start of the study and again at the end of the year.

The main number they tracked was brain-PAD, the gap between a person’s predicted brain age and their real age.

“We found that a simple, guideline-based exercise program can make the brain look measurably younger over just 12 months,” said lead author Lu Wan, a data scientist at the AdventHealth Research Institute.

“Many people worry about how to protect their brain health as they age. Studies like this offer hopeful guidance grounded in everyday habits. These absolute changes were modest, but even a one-year shift in brain age could matter over the course of decades.”

Inside the clinical trial

The clinical trial enrolled 130 healthy adults between 26 and 58 years old. Participants were randomly assigned either to an exercise program or to a usual-care control group that didn’t change its activity routine.

Those in the aerobic group followed a plan designed to match widely used fitness guidelines.

They completed two supervised 60-minute sessions each week in a lab setting and added home exercise to reach roughly 150 minutes of aerobic activity per week.

That target mirrors the American College of Sports Medicine’s (ACSM) recommendations for moderate-to-vigorous aerobic exercise.

To track changes beyond the MRI, the team also measured cardiorespiratory fitness using peak oxygen uptake, known as VO2peak, at the beginning and end of the 12-month period.

Exercise slowed brain aging

Over the year, the exercise group’s brain-PAD dropped by about 0.6 years on average. In plain terms, their brains looked a little younger at follow-up than they did at baseline.

The control group moved in the opposite direction, with an average increase of about 0.35 years, though that shift wasn’t statistically significant on its own.

What stood out most was the gap between groups. When the researchers compared the two trajectories, the difference in brain age was close to one full year, in favor of the people who exercised.

“Even though the difference is less than a year, prior studies suggest that each additional ‘year’ of brain age is associated with meaningful differences in later-life health,” said senior author Kirk I. Erickson, a neuroscientist and director at AdventHealth Research Institute.

“From a lifespan perspective, nudging the brain in a younger direction in midlife could be very important.”

Possible biological pathways

Exercise is known to improve many things that should, in theory, support brain health: cardiovascular function, blood pressure, body composition, and certain molecules involved in neural plasticity.

The researchers tried to see whether any of these changes could explain the shift in brain-PAD.

They examined several candidates, including fitness improvements, changes in body composition, and blood pressure.

Researchers also looked at levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) – a protein often linked to learning, memory, and the brain’s ability to adapt.

Fitness and exercise effects on brain age: A randomized clinical trial. Credit: Journal of Sport and Health Science. Click image to enlarge.More questions about brain aging

Fitness and exercise effects on brain age: A randomized clinical trial. Credit: Journal of Sport and Health Science. Click image to enlarge.More questions about brain aging

Fitness improved clearly in the exercise group, but none of the measured factors statistically accounted for the change in brain age within this trial.

“That was a surprise,” Wan noted. “We expected improvements in fitness or blood pressure to account for the effect, but they didn’t.

“Exercise may be acting through additional mechanisms we haven’t captured yet, such as subtle changes in brain structure, inflammation, vascular health, or other molecular factors.”

In other words, the brain age shift seems real in this dataset, but the “how” is still open. The answer may involve multiple small changes happening at once, or changes the study didn’t measure in enough detail.

The case for early prevention

A lot of exercise-and-brain research concentrates on older adults, when age-related changes are more obvious.

This trial aimed earlier, in early to mid-adulthood, when decline can be subtle and prevention may have more runway.

The idea is not that people in their 30s, 40s, or 50s are already destined for cognitive problems. It’s that brain aging is gradual, and intervening sooner might shift the slope in a way that pays off later.

“Intervening in the 30s, 40s and 50s gives us a head start,” Erickson said.

“If we can slow brain aging before major problems appear, we may be able to delay or reduce the risk of later-life cognitive decline and dementia.”

Future brain aging research

The researchers stress that the volunteers were healthy and relatively well educated, which can limit how broadly the results apply.

The brain age changes were also modest, even if the between-group difference was meaningful in context.

While brain-PAD is a promising biomarker, it’s still a proxy. Larger studies and longer follow-ups are needed to see whether shaving down brain age on MRI translates into fewer strokes or less dementia.

Additional research will also be needed to determine whether a reduced brain age leads to other measurable reductions in brain-related disease.

Still, for people looking for something practical to do now, the takeaway is refreshingly straightforward.

“People often ask, ‘Is there anything I can do now to protect my brain later?’” Erickson said.

“Our findings support the idea that following current exercise guidelines – 150 minutes per week of moderate-to-vigorous aerobic activity – may help keep the brain biologically younger, even in midlife.”

The study is published in the Journal of Sport and Health Science.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–