Japan’s Akatsuki mission officially ended in September 2025 after more than a decade of operations and a final year of complete radio silence. Launched in 2010 by JAXA and operated by ISAS, the spacecraft was designed to study Venus’s atmosphere, tracking cloud movements and extreme weather patterns. It remains Japan’s first fully successful planetary orbiter.

After a failed first attempt to enter Venus orbit, Akatsuki achieved a remarkable comeback in December 2015, following five years drifting around the Sun. From its long, elliptical orbit, it delivered valuable data and imagery that deepened our understanding of Venusian atmospheric dynamics, including super-rotation and gravity waves.

An Unexpected Second Chance

As Earth.com explained, the spacecraft initially missed Venus orbit due to a malfunction in its main engine shortly after its launch. Left looping around the Sun, it remained adrift for five years before JAXA engineers managed a second attempt using smaller thrusters. The maneuver succeeded, making Akatsuki the only operational spacecraft around Venus at the time.

At just over 1,150 pounds, the spacecraft was equipped with five imaging instruments and a sixth radio system to examine the atmosphere’s composition and motion. Its orbit varied from about 620 miles at its closest approach to 223,700 miles at its farthest, allowing for both wide-angle and detailed observations of Venus’s cloudy exterior.

Masato Nakamura, the project’s manager at ISAS, oversaw the operation as it transitioned into Japan’s first mission beyond Earth orbit. The team focused on remote sensing through imagery rather than direct sampling, enabling them to trace atmospheric motion across multiple altitudes.

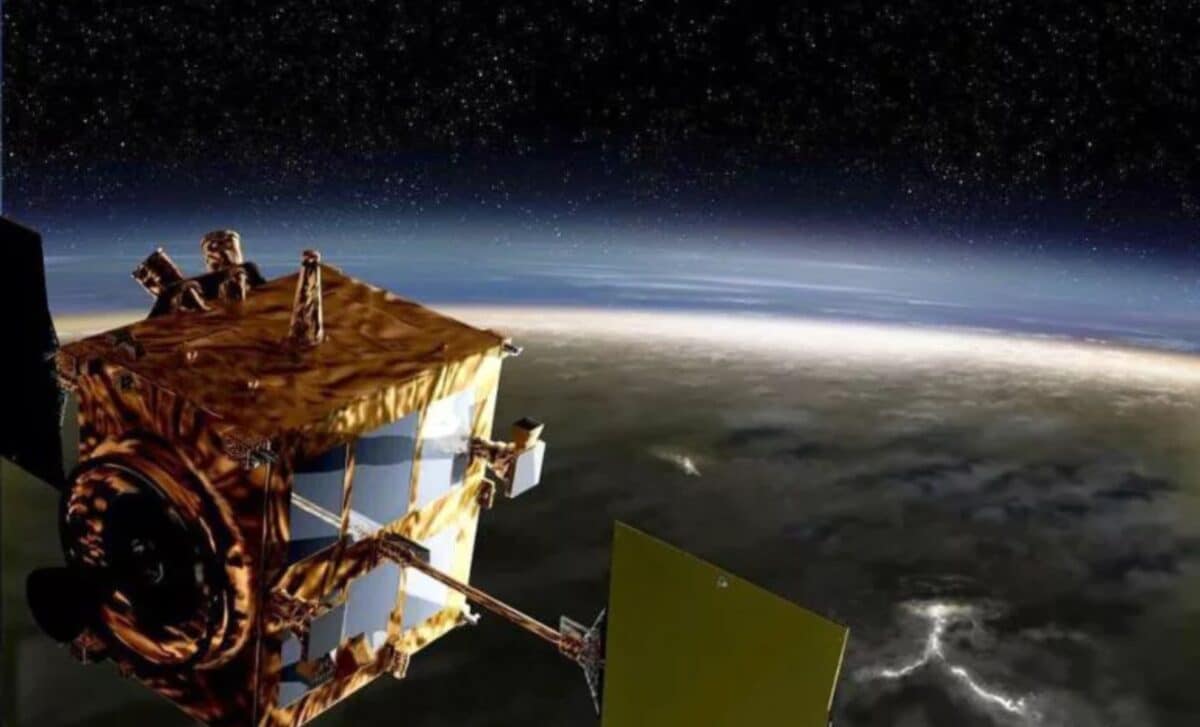

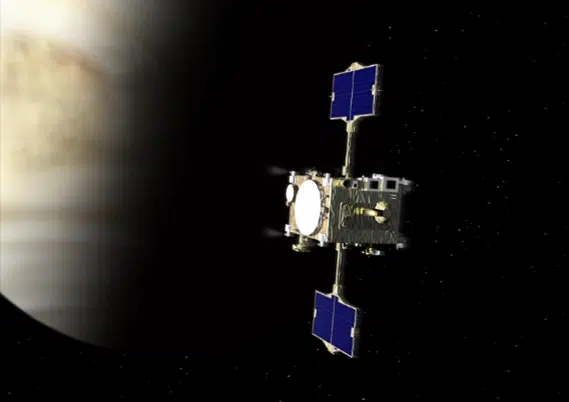

Artist’s impression of Akatsuki observing Venus from orbit. Credit: JAXA

Artist’s impression of Akatsuki observing Venus from orbit. Credit: JAXA

Tracking A Restless Atmosphere

Venus’s atmosphere is dominated by rapid winds and layers of thick, toxic clouds, making it a complex target for climate science. Akatsuki’s imaging instruments observed in both ultraviolet and infrared bands. Each spectral band corresponded to different altitudes, allowing scientists to build three-dimensional models of how the atmosphere flows.

Among its most striking observations was the discovery of a 6,200-mile-long stationary gravity wave, the largest of its kind in the Solar System. As reported, the wave appeared as alternating light and dark bands caused by air being pushed upward by mountainous terrain, suggesting that even Venus’s lower surface can influence its upper layers, despite the atmospheric pressure.

The mission also contributed to understanding the planet’s super-rotation, where the upper atmosphere moves significantly faster than the planet’s surface. This phenomenon had long puzzled researchers, but Akatsuki provided evidence linking wind acceleration to vertical momentum transfers via waves and turbulence.

This image of Venus was taken during Akatsuki’s 13th orbit. Credit: JAXA / ISAS / DARTS / Damia Bouic

This image of Venus was taken during Akatsuki’s 13th orbit. Credit: JAXA / ISAS / DARTS / Damia Bouic

Silence After the Switch-Off

In late April 2024, contact with Akatsuki was lost during a period of low-precision attitude control, where the spacecraft’s orientation and antenna positioning drifted off-target. Although the transmitter likely continued functioning, the radio signal could no longer reach Earth. According to Earth.com, engineers attempted for months to re-establish communication but ultimately deemed the orbiter beyond recovery.

The final command to terminate the mission was sent on September 18, 2025, just over 15 years after launch. JAXA officials confirmed that the aging systems and lack of signal left no option but to formally shut down operations. This ensured no uncontrolled signals would continue broadcasting from the inactive probe.

Despite the quiet end, the mission leaves behind a substantial archive of raw imagery, wind data, and experimental techniques. One notable achievement was the testing of data assimilation methods, which combine live data with predictive models to reconstruct more complete atmospheric dynamics, a first for any Venus mission.

NEWS🚨: Venus just lost its last active spacecraft, as Japan has officially declared the Akatsuki orbiter- which took some of the best IR images ever- dead. pic.twitter.com/QZsFFCtkJ4

— Curiosity (@MAstronomers) October 30, 2025