For Soledad Molina and her four children, the basics — light, heat, cooling, even a way to cook — are under constant threat.

The 45-year-old Portland mother fell behind on her electricity bills last winter as rates soared and the region was hit by extreme weather, racking up a balance of more than $1,000. In June, Portland General Electric shut off her power for a day and night. A state assistance program helped pay the balance, but reconnection fees and new charges quickly piled up again.

Molina, who lost her job cleaning houses last year, also fell behind on rent payments and received an eviction notice this fall, forcing her to choose between utilities and housing. Today, she again owes PGE hundreds of dollars and fears another shutoff at any moment.

“My bills are competing for the little money I have available,” said Molina, who currently relies on limited child support and food stamps to stay afloat. “It’s simple: either I pay the rent, buy food or pay the electricity bill, but I can’t do all three.”

Across Oregon, energy bills for residential, commercial and industrial customers of investor-owned utilities PGE and PacifiCorp — which serve two thirds of electricity users in the state — have soared in the past six years. Nearly 58,000 residents had their power disconnected last year, the highest number on record. Consumer advocates say many other lower-income households are just a few dollars away from losing power.

A PGE customer for 24 years, Molina said her bills rarely topped $100 a month until recently. They now run $200 to $300 — even after the family cut back on their heating and AC use and enrolled in the utility’s bill discount program.

The impact is economy-wide. The Pacific Northwest has historically enjoyed some of the cheapest electricity rates in the country, a key advantage for businesses and one that has helped keep the cost of living in check.

But national figures show that differential has disappeared. And the squeeze on customers could potentially get worse.

Experts predict bills could climb sharply as Oregon’s investor-owned electric utilities grapple with an unprecedented build-out of solar, wind and battery storage projects to meet ambitious state climate mandates, and a surging appetite for energy from data centers.

Oregon’s looming energy crunch

This is Part 3 of a series about the ability of Oregon’s largest electric utilities to meet the interlocking challenges of decarbonizing the grid while maintaining affordable and reliable service.

Part 1: The region’s soaring energy demand, coupled with supply constraints, could spark a new power crisis.

Part 2: Utility progress toward looming green power mandates has been slow, throwing doubt on their ability to meet the targets and adding to the costs.

Part 3: Will consumers, already struggling with steep utility rate increases, pay for Oregon’s climate ambitions and data center boom? Can new legislation, dubbed the Power Act, shield customers from surging electricity costs?

Part 4: There are possible solutions to Oregon’s looming energy crisis, but many are expensive or unproven — and nearly all would take years to implement.

Oregon’s largest electric utility, PGE, has forecast that its cost to generate every megawatt of electricity will double in the next five years, triple in 10 and quintuple in 15 years. Power generation costs are only one component of customers’ rates. Others, like transmission and distribution rates, are rising, too, as utilities add capacity and make upgrades to reliably deliver power to customers.

PGE, which serves about 930,000 customers in Oregon across seven counties and 51 cities, has not forecast future rate impacts in filings with state regulators.

In a filing with state regulators this week, PacifiCorp provided an eye-popping estimate of its costs to comply with the emission mandates: between $135 million and $2.5 billion a year for the next two decades. It said those would translate to an “average annual incremental rate impact” between 10% and 140% of its 2025 costs. PacifiCorp serves more than 620,000 customers in Oregon.

“The current plan for clean energy deployment in Oregon will impact the cost of living for Oregonians and is becoming increasingly risky for utilities,” Omar Granados, a spokesperson for the utility, said in an email.

Bob Jenks, executive director of the Oregon Citizens’ Utility Board, said PacifiCorp may legitimately face high costs to comply with the emissions mandates in any given year, but the way it presented annual rate impacts in the filing “is misleading.” The law, he added, also allows regulators to temporarily exempt utilities from the mandates if compliance would increase their costs of service by 6% or more.

“This is not a legitimate rate forecast,” he said.

Bob Jenks, executive director of Oregon Citizens’ Utility Board, sits at his desk in downtown Portland. Sean Meagher/The Oregonian

Bob Jenks, executive director of Oregon Citizens’ Utility Board, sits at his desk in downtown Portland. Sean Meagher/The Oregonian

Nevertheless, lawmakers are already alarmed by rising costs. They’ve put some Band-Aids on the affordability problem, including limiting how often residential rate increases can occur and doubling funding for bill assistance programs from $20 million to $40 million a year. And the Oregon Public Utility Commission has previously approved temporary moratoriums on service disconnections for non-payment during winter cold snaps and summer heat waves.

The Legislature also passed a new law earlier this year designed to make data centers pay for their own transmission and energy costs. But it’s unclear whether the legislation will buffer other customers from higher power bills.

“The Power Act will clearly make a significant difference,” said Jenks. “But I can’t guarantee that rates with the Power Act will be affordable because of all the costs utilities are facing.”

PGE rates higher than national average

The Columbia River’s vast hydroelectric system, a cheap, abundant and clean power source, has long kept costs low in Oregon and across the Pacific Northwest.

When the surplus of cheap hydro power started to run out in the 1970s, aggressive energy efficiency programs adopted in Oregon dramatically reduced overall electricity usage, helping keep rates and bills down. Meanwhile, the national average for household electricity use continued to steadily increase.

Efficiency measures included stricter building codes for new construction, incentives for energy-saving appliances and HVAC systems and rebates for home weatherization. Businesses made their processes more efficient. And widespread adoption of compact fluorescent bulbs, and later LEDs, dramatically reduced lighting energy use. The measures freed up capacity on the grid so utilities didn’t have to generate or purchase as much electricity.

But in recent years, those measures haven’t been enough to shield Oregonians from rising power costs. Electric rates surged dramatically between 2019 and 2025 for all customer classes. PGE’s residential rates rose by 61% over that time period, after compounding; commercial by 53.5% and industrial by 48%. (Compounding means that if a customer gets an increase in one year and another increase a year later, the second increase is applied to the already-higher rate.)

PacifiCorp’s residential customers saw an increase of 39% between 2020 and 2025.

Oregon is hardly an outlier; customers in other states have seen similar or even larger increases.

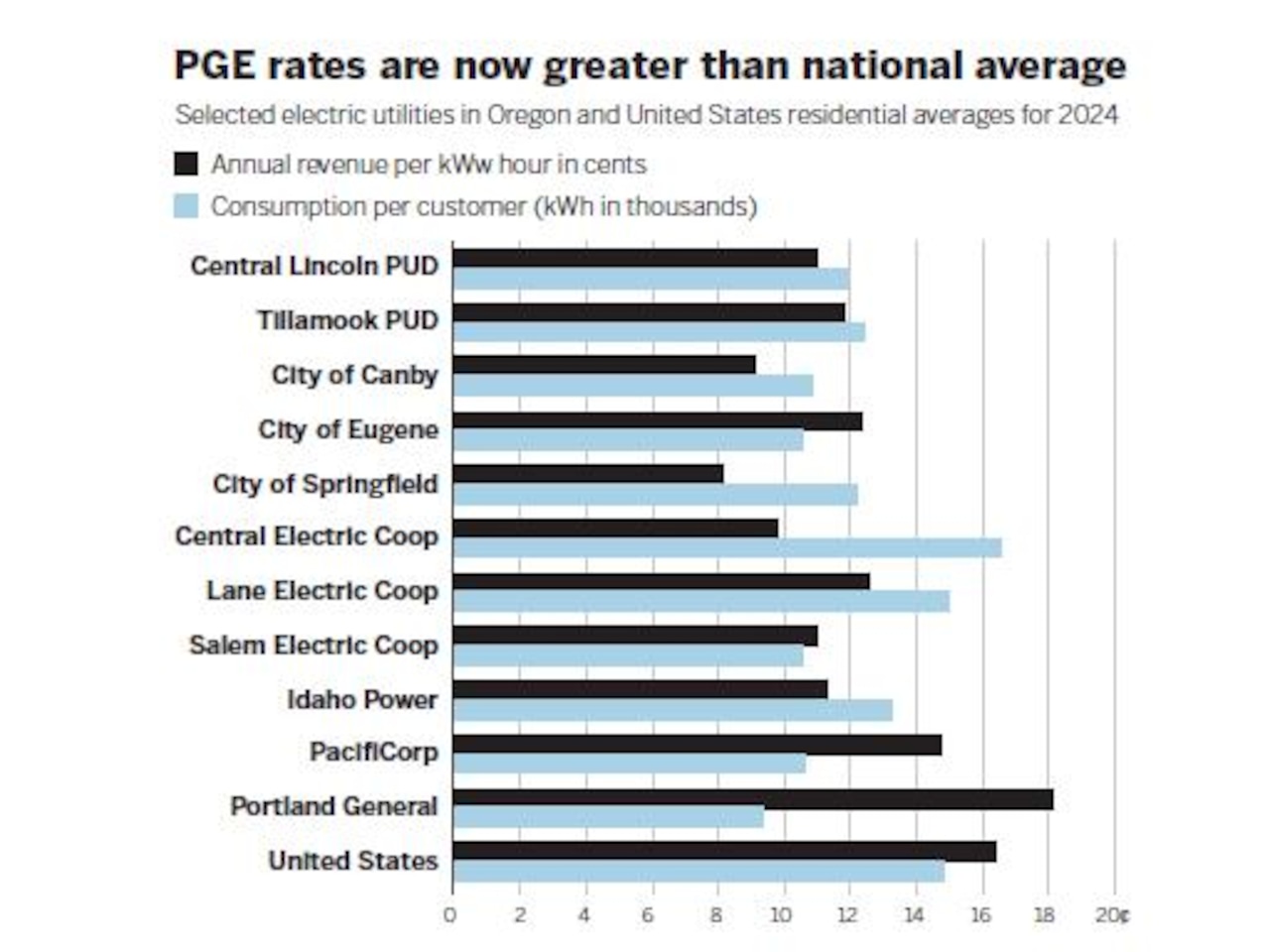

Oregon’s average residential electricity rate remains 1.5 to 3 cents per kilowatt-hour below the national average, according to data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration. But the average obscures the rates of investor-owned utilities like PGE and PacifiCorp by combining them with public utilities and cooperatives that buy their power from the federal hydroelectric system and typically charge far less.

In fact, residential electric rates for PGE are now higher than the national average, according to the Oregon Public Utility Commission. But PGE customers are still using significantly less energy than customers across the nation, thanks to a continued push on energy efficiency.

source: Oregon Public Utility CommissionOPUC

source: Oregon Public Utility CommissionOPUC

Many Oregon households, like Molina’s, have been unable to keep up. Businesses are feeling the pressure, too.

“For small businesses, the fixed costs of doing business have gone up across the board, including rent, insurance and electricity,” said Britt Marra, executive director National Small Business Utility Council, a nonprofit that advocates for small businesses in Oregon and Washington. “So they’re very concerned about the future of energy affordability and the grid.”

Costly decarbonization, transmission upgrades

The surge in electric rates over the past six years in Oregon corresponds with a spike in demand, the vast majority of which stems from the growth of electricity-hungry data centers across the state. Forecasts show data center demand will continue to soar, consuming dramatically more energy than power planners had anticipated.

Residential consumption also has increased, mostly during peak-demand periods, as more households depend on heat pumps and air conditioners to make it through prolonged winter cold snaps and summer heat waves, driving sharp spikes in electricity demand when energy prices are highest.

Rising demand has forced utilities to buy vast amounts of electricity on the wholesale market, often pricey purchases that have been a significant factor in recent rate increases, utilities have said.

Meanwhile, aggressive state climate targets require utilities to wean off fossil fuels and procure energy from wind and solar farms, and back it up with battery storage. Those resources will require billions of dollars in upfront investments, and costly upgrades to transmission and local distribution systems to deliver the power to customers.

Wind turbines at Klondike wind farm in Sherman County, Oregon.

Wind turbines at Klondike wind farm in Sherman County, Oregon.

Climate change and resulting wildfire risks are also driving higher expenses for insurance, monitoring and maintenance of transmission corridors. And utilities’ borrowing costs are increasing as rating agencies downgrade debt ratings to account for higher risks. PacifiCorp, in particular, is facing billions of dollars in liabilities related to damages from the catastrophic wildfires of 2020.

Those costs are only going to rise. Just as Oregon’s large electric utilities are ramping their renewables investments to meet 2030 climate goals, generous federal tax credits are ending after being dismantled by the Trump administration. Those credits have historically lowered the cost of clean energy projects on PGE’s system from 20% to 40%, said Kristen Sheeran, PGE’s vice president of policy and resource planning.

“That’s a lot of value that is going away and it will necessarily increase the cost of clean energy projects going forward,” Sheeran said.

All told, those costs could drive utility bills over the edge, said Jenks with the Citizens Utility Board.

“The issue isn’t, can we afford a big increase in power costs. The issue is, can we afford that, combined with the big cost increases in distribution and transmission,” said Jenks. “PGE has this idea that they can do everything, and I’m skeptical that everything is affordable.”

Will the Power Act save the day?

The multibillion-dollar question is whether households and small businesses will foot the bill.

Legislation passed in June, dubbed the Power Act, aims to shield residential customers from the costs of meeting data centers’ voracious power demands. The law requires investor-owned utilities to create a new class of customers for large energy users and charge them for their own energy costs. It directs the Oregon Public Utility Commission to allocate costs to the data centers based on how much power they consume and how that drives statewide investments in electricity generation, transmission and distribution.

A Google data center operates in The Dalles, near the Columbia River, on Monday, December 1, 2025.Vickie Connor/The Oregonian

A Google data center operates in The Dalles, near the Columbia River, on Monday, December 1, 2025.Vickie Connor/The Oregonian

While the law must be fully implemented by 2028, key details — such as how costs will be allocated and what rates data centers will pay — still need to be determined by the Oregon Public Utility Commission.

Already, a PGE proposal on how to divvy up the costs has sparked controversy.

This fall, the Citizens’ Utility Board accused the utility of undermining the Power Act by attempting to shift an outsized share of the costs of powering data centers onto residential customers.

PGE proposes to assign electricity costs based on who is causing the growth in peak demand — the times when electricity use is at its highest level — to ensure all customers “pay their fair share of the system costs,” said the utility’s spokesperson Drew Hanson.

“The principle is simple. Customer groups driving peak-demand growth should pay for the infrastructure needed to serve that growth,” Hanson said.

While data centers have been driving overall system load growth, Hanson said, residential customers’ adoption of air conditioners, heat pumps and other household electrification has fueled increases in “peak demand,” during cold snaps and heat waves.

Residential customers account for 45% of recent system growth, specifically increases to system peak demand, said Hanson. Building new transmission lines and adding more generation and storage will ensure residential customers have reliable energy when demand is at its highest, he said.

Jenks of the Citizens’ Utility Board said it was “absurd” to ask residential customers to shoulder up to half the cost of generating and moving more power given that demand for electricity from the residential sector has barely increased.

“PGE’s system without the data centers isn’t growing,” Jenks told The Oregonian/OregonLive, adding that household adoption of energy efficiency measures has fully offset the residential peak load growth in recent years.

Facing pushback, PGE scaled back parts of its proposal. The utility says it now supports factoring in residential customers’ investments in energy efficiency when allocating generation and transmission costs.

That’s a step in the right direction, said Jenks. But, he added, PGE still wants to charge consumers “far too much” of the cost of generating power and building new wind, solar and storage projects and transmission lines.

“Where the costs of new transmission and generation are being driven by data centers, they should be assigned to the data centers and paid for by them,” said Jenks. Cost allocations can be revisited if a data center leaves after 20 years and the investments end up serving other customers, he added.

PGE opposes assigning costs to data centers permanently, arguing that new generation and transmission investments benefit all customers, not just data centers. Instead, the utility wants the data centers — the customers driving growth and creating new demand — to cover the first 10 years of a power investment that typically lasts 50 years. After that, all customers, including households, would share costs for the remaining years based on how much they contribute to the system’s peak electricity use.

PGE argues that, assuming data centers continue to grow as predicted, they’re likely to become the future drivers of peak demand growth and larger users of the system overall, so more costs would be allocated to them.

If PGE’s proposal is adopted, the utility says data centers will see an immediate 26% rate increase. Residential and small commercial customers will see their rates decrease by 2%. It’s unclear what rates would look like after that.

But Jenks said asking data centers to cover only a small portion of the upgrade costs and then spreading the rest across all customers is “woefully insufficient.” Households and small businesses could face steep increases after the first decade, he said, especially if fewer additional data centers come online in later years.

Public accountability

Oregon residents and activists are increasingly demanding that the commission ensure data centers pay their fair share.

On a cold Saturday in October, Be Marston stood at the Portland Farmers Market at Portland State University, handing out leaflets warning that data centers are driving up household electricity bills. Marston is a member and union organizer with UNITE HERE Local 8, which represents about 4,000 food service and hospitality workers in Oregon and Washington. The union members are working with other local nonprofits and the utility board on a campaign to ensure tech companies pay for rising demand.

“Everyone I talked to was like, ‘those data centers are awful, they’re disastrous for the environment, they’re not creating any jobs and we’re subsidizing their power bills,” Marston said. “People are really engaged on this issue and really angry.”

The anger doesn’t come as a surprise, she said. Low-income people — including unionized cafeteria and dining workers at Google and Meta, which operate data centers in Oregon — are living paycheck to paycheck, struggling to pay rising electric bills as food and health care costs also climb, Marston said. Meanwhile, tech companies are reaping rising profits from data center-powered services such as cloud platforms and artificial intelligence.

Be Marston, a member and organizer with UNITE HERE local 8, sits in Portland’s South Park Blocks on Thursday, Dec. 11, 2025. Marston is working on a campaign to ensure tech companies pay for data centers’ rising hunger for electricity. Sean Meagher/The Oregonian

Be Marston, a member and organizer with UNITE HERE local 8, sits in Portland’s South Park Blocks on Thursday, Dec. 11, 2025. Marston is working on a campaign to ensure tech companies pay for data centers’ rising hunger for electricity. Sean Meagher/The Oregonian

Marston, who also works as a bartender, said most Oregonians don’t know about the existence of the Power Act, much less that the utility commission will be crafting rules to implement it through an opaque process that’s inaccessible to most customers.

“This stuff is kind of happening in the dark and slipping under the radar,” Marston said. “But I think if they know the public is watching, it could help move the needle on this.”

Oregonians have taken notice. To date, PGE’s Power Act docket before the PUC has received 1,642 public comments, the second most on any issue since 1987, when the current docket system was created.

Mike Rogoway and Ted Sickinger contributed to this article.