Research led by scientists at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST) and Stanford University has demonstrated a new approach to Floquet engineering using excitons rather than photons. Floquet engineering is a field of physics in which scientists attempt to design new materials by shining light on them.

This approach in modern science might sound like attempts at alchemy, and on the face of it, Floquet engineering is attempting alchemy, but it aims to modify the material’s quantum states.

A relatively new field, it rests on the theory that when a system is subjected to repeated external forces, its overall behavior is richer than the forces themselves.

To explain this, scientists often cite examples of a pendulum or a swing. In both these cases, the repeated external force, also known as a periodic drive, lifts the pendulum or swing to greater heights even though the object is only oscillating back and forth.

Using this principle, scientists aim to imbue exotic quantum properties into ordinary materials.

How does this happen?

In materials such as semiconductors, atoms are arranged in a tight lattice, while electrons are confined to specific energy levels or bands defined by the atoms’ structure. When light at a specific frequency is shone on the atom, the electromagnetic photons interact with the electrons, shifting their energy bands.

By tuning the frequency and intensity of light, electrons can also be made to occupy hybrid bands, thereby altering the material’s properties. When the light source is switched off, the electrons return to their original energy bands, restoring the material’s properties.

While this has been used to demonstrate Floquet effects, light couples weakly with matter, requiring very high frequencies to achieve hybridization.

“Such high energy levels tend to vaporize the material, and the effects are very short-lived. By contrast, excitonic Floquet engineering requires much lower intensities,” said Xing Zhu, PhD student at OIST, who was involved in the research.

The time- and angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (TR-ARPES) setup at OIST. Image credit: Bogna Baliszewska (OIST)

The time- and angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (TR-ARPES) setup at OIST. Image credit: Bogna Baliszewska (OIST)

How can excitons help?

Excitons are formed in semiconductors when electrons are excited from their valence band to a higher energy level, or the conduction band, by photons.

This leaves a positively charged hole in the valence band, and, along with the negatively charged electron, forms a quasiparticle called an electron-hole pair, which exists until the electron falls back into its valence shell.

“Because the excitons are created from the electrons of the material itself, they couple much more strongly with the material than light,” explained Gianluca Stefanucci, professor at the University of Rome Tor Vergata, in a press release.

“And crucially, it takes significantly less light to create a population of excitons dense enough to serve as an effective periodic drive for hybridization.”

To investigate if excitons could be used to extract Floquet effects, the researchers at OIST first excited a semiconductor with a light drive. After measuring the energy levels of electrons, the researchers then dialled down the optical drive by an order of magnitude and measured the electron signal 200 femtoseconds later, to capture Floquet effects independent of the optical drive.

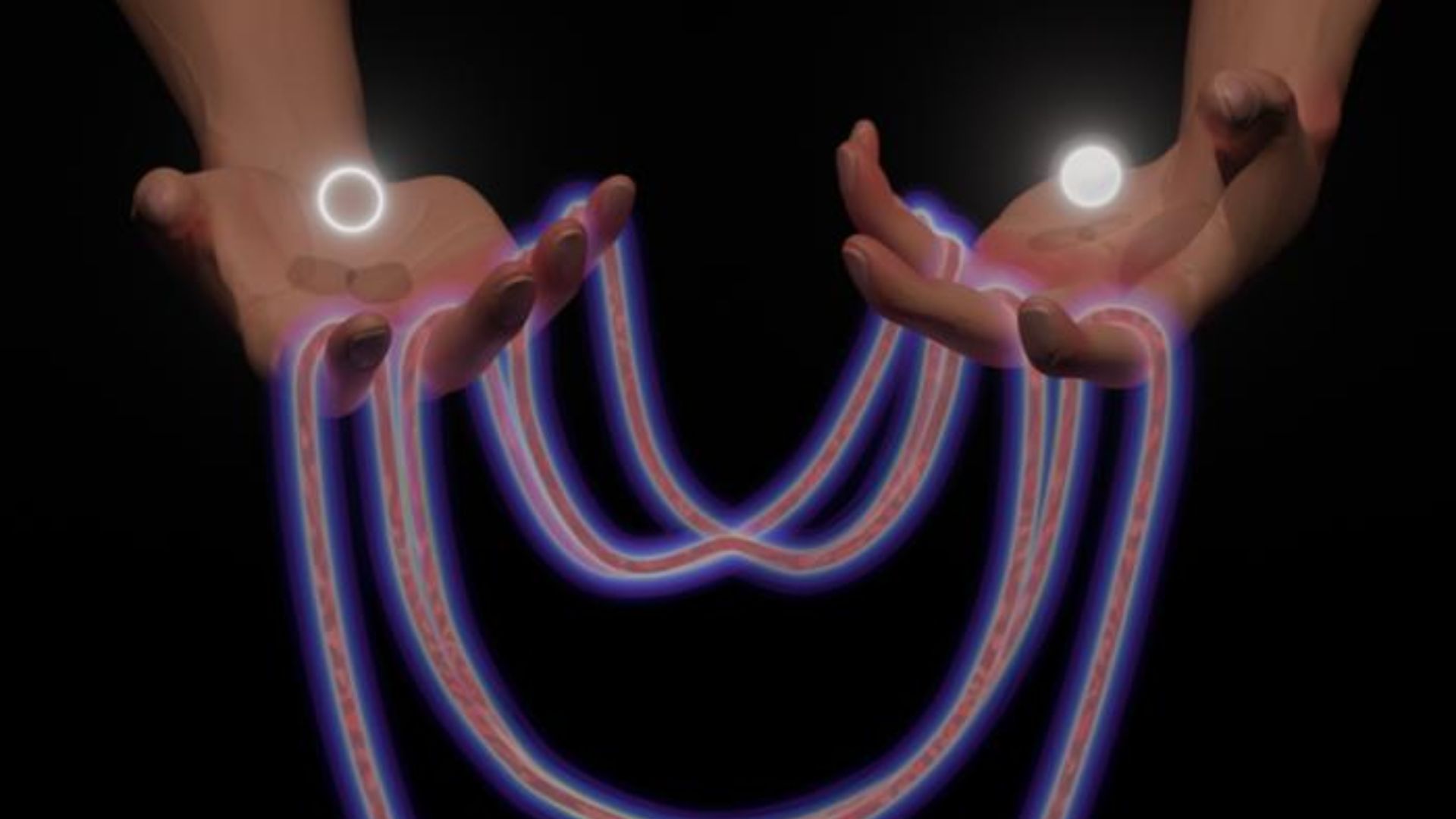

A 3D rendering of a pair of hands holding glowing bands of energy like a cat’s cradle. One of the bands folds inwards, reminiscent of the Mexican-hat-like momentum dispersion indicative of Floquet effects. The glowing orbs above the hands, one dark and the other light, represent the electron and hole that together form an exciton.

A 3D rendering of a pair of hands holding glowing bands of energy like a cat’s cradle. One of the bands folds inwards, reminiscent of the Mexican-hat-like momentum dispersion indicative of Floquet effects. The glowing orbs above the hands, one dark and the other light, represent the electron and hole that together form an exciton.

“It took us tens of hours of data acquisition to observe Floquet replicas with light, but only around two to achieve excitonic Floquet – and with a much stronger effect,” said Vivek Pareek, postdoctoral fellow at California Institute of Technology, who was a graduate student at OIST when the work was done.

The discovery is exciting not just because it moves away from light drives, but also because it opens up a wide range of excitation options, such as phonons (acoustic vibrations), plasmons (free-floating electrons), and magnons (magnetic fields), in the future.

The research findings were published in the journal Nature Physics.