HIV/AIDS activist Saundra DeAnné Johnson died Jan. 21 due to complications from chronic congestive heart failure and kidney failure illnesses. She was 65.

Saundra Johnson in Minneapolis, Minnesota in 2021. Photo by Becca Olsen

Saundra Johnson in Minneapolis, Minnesota in 2021. Photo by Becca Olsen

Johnson, an out queer woman, was born Oct. 13, 1960, and grew up in Chicago’s Woodlawn neighborhood. She graduated from Hyde Park Academy High School. One of the things she did while in high school was work as a candy striper for a program where students could get credits towards graduation. Johnson said she “really liked it.”

She moved to Albuquerque, New Mexico to attend the University of New Mexico for a brief period. While she was in college she was crowned Miss Albuquerque by the University of New Mexico.

Johnson returned to Chicago for personal reasons and completed her education at Chicago City-Wide College where she received an Emergency Medical Technician-Ambulance Certificate in 1983 and an Associates of Arts with Honors in Liberal Arts and Science from Harold Washington Community College in 1985.

University of Chicago rowing team members with Saundra Johnson (middle center) and Adam Burck to the direct right of the man in the white sweatshirt. Photo courtesy of Burck

University of Chicago rowing team members with Saundra Johnson (middle center) and Adam Burck to the direct right of the man in the white sweatshirt. Photo courtesy of Burck

While Saundra Johnson was working as an administrative assistant at the University of Chicago in 1986, she decided to go to a learn-to-row session even though she didn’t know how to swim. This is how she ended up rowing for the University of Chicago crew and where she met what she calls “wonderful people,” including HIV/AIDS activist Adam Burck, who helped jump-start her HIV/AIDS activism journey.

In a 2020 Chicago Magazine article that featured her and other Chicago HIV/AIDS activists she said, “I had read And the Band Played On, and it made me so mad. I told Adam, and he said, ‘Why don’t you volunteer at the NAMES Project? You know, a big display is coming, the quilt.’ I volunteered there the whole weekend. Oh my God, it was transformative.”

Saundra Johnson and other ACT-UP activists protesting then President George H.W. Bush HHS Secy Louis Sullivan in San Francisco. Photo courtesy of Edd Lee’s Facebook page

Saundra Johnson and other ACT-UP activists protesting then President George H.W. Bush HHS Secy Louis Sullivan in San Francisco. Photo courtesy of Edd Lee’s Facebook page

Johnson quickly got involved with ACT-UP Chicago after that weekend volunteer stint with the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt display, where she was also a member of the Women’s Caucus. One of the things she did for ACT-UP Chicago was pose for their safer sex t-shirt campaign in the early ‘90s.

Mary Patten, Saundra Johnson and Debbie Gould at the Freedom Bed protest action in the fall 1989. Photo by Steve Dalber

Mary Patten, Saundra Johnson and Debbie Gould at the Freedom Bed protest action in the fall 1989. Photo by Steve Dalber

“We staged lots of demonstrations with ACT-UP Chicago,” said Johnson shortly before her death. “I helped organize them as a worker bee. We also had fun doing this work, especially us girls. We did the freedom bed action at the state of Illinois plaza in [Chicago’s Loop neighborhood] to protest for abortion rights. The boys got mad about this, so that’s why there was a split in the organization because the men wanted to focus only on drug access for HIV/AIDS patients and we women wanted to do more than that. I learned a lot about activism during that time.”

Johnson also participated in abortion clinic defense work outside of Planned Parenthood locations where she was arrested for the first time. She was a Chicago Women’s AIDS Project volunteer at the time. One Saturday, Johnson was arrested during one of those abortion clinic defense actions (she called right-to-life people “vicious”) and she used her one phone call to contact Chicago Women’s AIDS Project Executive Director Cathy Christeller to let her know that she could not do her volunteer childcare shift that Saturday.

After Johnson told Christeller she was arrested, the first thing Christeller asked was if she needed money to be bailed out. Christeller also offered Johnson a paid job, so she became an HIV Case Manager and Community Treatment Advocate for the organization. She was in that role from 1990-1993.

“I’m very proud of the work I did as a case manager for the Chicago Women’s AIDS Project,” said Johnson. “Not only did we take care of the women, but we also took care of their families, including men coming back from prison. Having those difficult talks where we asked them about various sensitive topics including what they did sexually while in prison.”

Christeller said, “It was an intense time back then trying to help families cope with what was then a devastating illness. Working with women living in poverty who were infected through their partners or their own substance use histories and were also rejected by their family members took a toll on Saundra. She was a results oriented person and felt pained by the limits of what she could do in that role. I loved Saundra’s fighting spirit. She jumped in to do hard things when others would shy away. Saundra did all of this with a joyful spirit.”

Saundra Johnson in front of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2022. Photo by Becca Olsen

Saundra Johnson in front of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2022. Photo by Becca Olsen

Johnson worked for the Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC) in New York City as a Medical Information Intern and then a Treatment Education and Adherence Services Coordinator from 1993 to 2005 where, among her other duties, she was a contributing writer for their Treatment Issues HIV newsletter and media spokesperson on HIV medical issues. While Johnson lived in New York City she got a Supervisory Management Certificate from the Center for Nonprofit Management in 2003.

Her other professional endeavors included as a Black AIDS Institute African American HIV University Core Faculty member from 2000 to 2010, Aliveness Project Health and Wellness Coordinator and a health educator independent contractor.

During the 1990 National AIDS Action for Healthcare protest in Chicago, Johnson was in charge of the soup kitchen (with food provided by former Chicago Ald. Tom Tunney’s Ann Sather restaurant) that was set up outside of Cook County Hospital.

Her activist/advocacy work also included her time as a volunteer with Open Hand Chicago as a runner for South Side delivery locations in the late 1980s. She was also a member of the now-defunct Ad Hoc Committee of Proud Black Lesbians and Gays ,and was instrumental in their inclusion in Chicago’s Bud Billiken Parade in 1993.

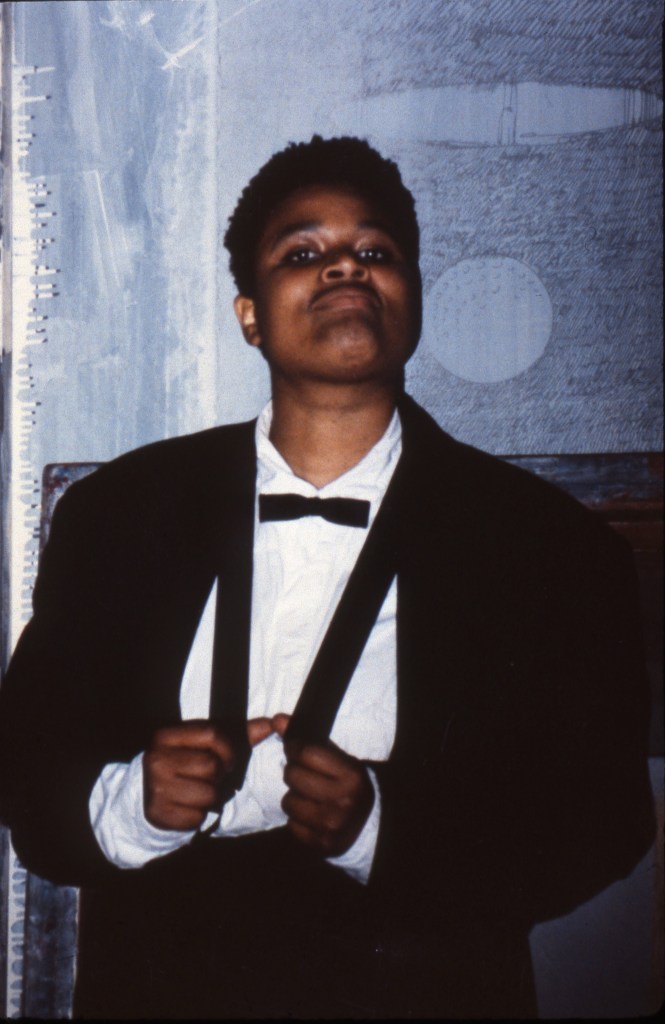

Saundra Johnson in drag circa 1991. Photo courtesy of Mary Patten

Saundra Johnson in drag circa 1991. Photo courtesy of Mary Patten

Johnson was on numerous advisory boards including AIDS Foundation Chicago, Horizons Community Services (now Center on Halsted), Chicago Community Programs for Clinical Research on AIDS, Northwestern University Medical Center AIDS Clinical Trials Unit and Life Beat: Music Industry Fights AIDS. She was also an HIV Infection in Women National Conference steering committee member from 1993-1995, and a National Conference on Women and HIV executive board member. Johnson additionally served on both the HIV/AIDS Collaborative Group of the U.S. Public Health Service Office on Women’s Health and New York City Women’s HIV Collaborative.

After Johnson was diagnosed with type two diabetes and congestive heart failure she participated in a 2018 Pro Publica/New York Times collaborative piece where she spoke about how the high cost of drugs impacted her healthcare.

In an effort to share more about her work as an HIV/AIDS activist, Johnson wrote a piece for TPAN’s Positively Aware publication in 2021. She was also interviewed for and appeared in the 2023 WTTW Chicago Stories series documentary, The Outrage of Danny Sotomayor.

Johnson moved to Minneapolis in 2007 to live with her sister Shirley Durr. She resided there until her death.

Although Johnson could not participate in protests in recent years, she was an advisor to other activists during the 2020 protests after George Floyd was murdered by now convicted felon and former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, and in recent weeks as people have been protesting and protecting their fellow community members against ICE and Border Patrol actions in Minneapolis and the surrounding region.

“Protesting is dead serious but it also can be fun and empowering to stand up for what you believe in,” said Johnson.

Rebecca Olsen and Saundra Johnson in 2017. Photo courtesy of Olsen

Rebecca Olsen and Saundra Johnson in 2017. Photo courtesy of Olsen

She is survived by maternal aunt Twila Williams Hatcher, brother Anthony Johnson, sister Shirley Durr, sister-friend Rebecca Olsen, one niece, three grandnieces, four nephews, four grandnephews, a plethora of cousins and countless chosen family members and friends. She was preceded in death by her biological mother Alfriell Hendrickson, her adopted parents Mary and James Wire and her maternal grandparents Allen and Katie Johnson.

Friends remember Johnson

Olsen said, “Saundra was a masterful orchestrator and logistical genius who taught me everything. I will keep her memory alive for the rest of my life. I will miss her and presence every single day.”

Adam Burck said, “When I met Saundra on the U of C crew team in 1986, her outgoing and friendly personality drew me to her and we became instant friends. I invited her to an ACT-UP Chicago meeting and she took to it immediately. My amazingly positive and supportive friend was always a fierce activist for her entire life. I will miss Saundra more than words can express and she has a special spot in my heart.”

Edd Lee said, “Saundra leaves behind a legacy of knowledge, compassion and community spanned decades, distance and diversity. Her unique ability to understand complex scientific information and translate it for doctors, advocates and patients alike improved the quality of life for people living and dying of AIDS during the darkest days of the pandemic. Her compassionate, passionate heart made her a constant force in her work with ACT-UP, the national African American/Black AIDS response and the national LGBTQI+ African American/Black movement. But in person, her passion for love, kindness and caring still shines brightly. She really was the person to give away her last dollar to a stranger in need. And she loves her people fiercely and without end. The world will be a less magically loving place without her.”

Saundra Johnson and Mary Patten in 2022. Photo courtesy of Patten

Saundra Johnson and Mary Patten in 2022. Photo courtesy of Patten

Mary Patten said, “I can’t really talk about Saundra in the past tense. She is very present to me, as she must be to everyone who knew her. Saundra was a fierce activist in ACT-UP Chicago, a leader of both the people of color and women’s caucuses, but you’d never know that from talking to her. She was so self-effacing. Last week she described herself as ‘just a worker bee.’ Not true. Saundra was a crucial and vibrant part of the whole organization, a really important bridge between different communities, tendencies and factions. She was a great organizer, fiery public speaker and a passionate, dedicated and loyal friend.

“She had a really great sense of humor, too. We had some crazy times together, like the ‘freedom bed’ street theatre action in downtown Chicago, where Saundra showed up wearing her ‘Study Naked’ t-shirt. Saundra was often the only Black woman in the room, but she saw us all as part of her family, despite the racism in and around us. Shortly after Christmas, I sent Saundra some photos of a snowstorm out East. I was messaging her to plan to have a zoom or a phone visit, unaware that she had spent most of the fall in the hospital. It’s very typical of Saundra to send a cheery note, ‘a winter wonderland!’ but say nothing of her suffering.”

Tim Miller said, “Saundra was always doing the work to help people. This all occurred during the dark days of HIV/AIDS in the 1980s and early 1990s. I remember working with Saundra first on the Lyphomed, Inc. action to bring down the cost of Pentamidine. After that action, Lyphomed reduced the cost of their drug which treated PCP pneumonia. We also helped to plan ACT-UP Chicago’s National AIDS Action that occurred in April 1990. It was an important multi-pronged demonstration. Saundra was a fierce activist and always gave 100%. Chicago was lucky to have her during that time.”

Bill McMillan, Saundra Johnson and Adam Burck outside of a restaurant in 2022. Photo by Becca Olsen

Bill McMillan, Saundra Johnson and Adam Burck outside of a restaurant in 2022. Photo by Becca Olsen

Bill McMillan said, “I am grateful to have had Saundra as a dear friend and comrade in arms. She was a human rights champion and the heart and soul of ACT-UP Chicago. What described her the most was her belief that every person deserves dignity, safety and a voice. In meetings, on the streets and in private conversations, Saundra reminded us that human rights are not an abstraction, but a promise we make to each other. It was an honor and privilege to know Saundra and to act up with her. This is a huge loss for the community of people who do good deeds and work. I will miss her very much.”

Lee has set up a GoFundMe to help pay for Johnson’s end of life expenses.

A celebration of life will be held in Minneapolis at a later date.

Related