San Antonio’s leaders have been funding the needs of a growing community without increasing the property tax rate for more than three decades.

But as the city embarks on two new downtown sports districts and a $1.3 billion airport redevelopment this year, the City Council will soon have to decide whether to embrace a financial plan that commits them to raising taxes — or scales back drainage and infrastructure projects elsewhere in the city — if flattening revenue doesn’t bounce back.

On Wednesday, the council got its first major financial update since voters approved the public funding for a new Spurs NBA arena at Hemisfair in November.

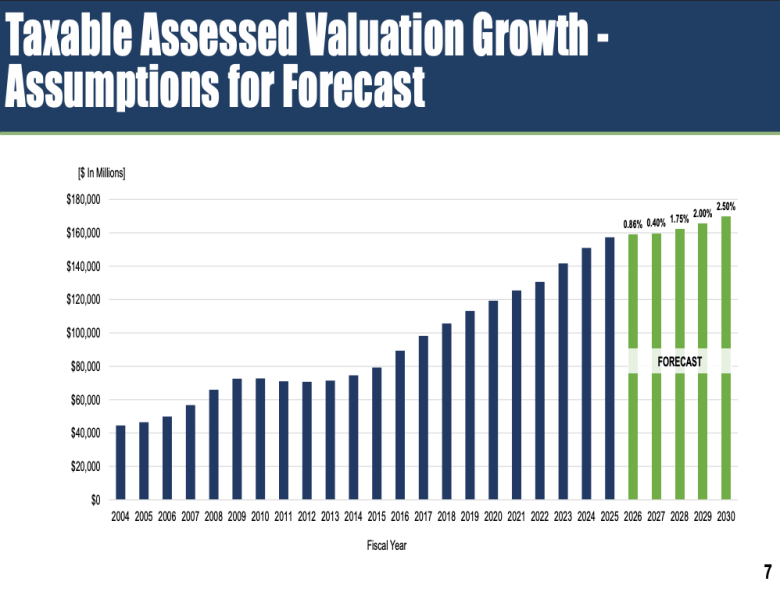

The growth forecast largely matched what they knew going into the project last summer, with property tax revenue increasing by less than 1% from fiscal year 2025 to 2026, and an even smaller margin in the year after that.

Yet council members who’ve supported development initiative after development initiative now face the unpleasant reality of trying to fund them all at a time when resources are scarce amid economic uncertainty and rising costs.

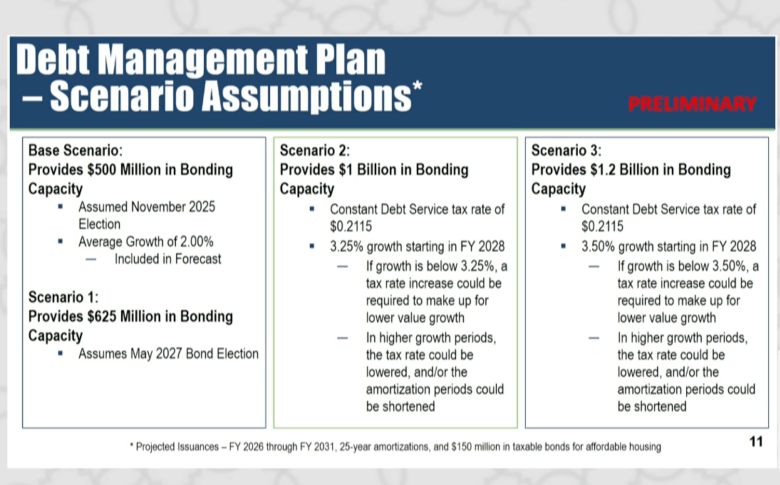

Chief Financial Officer Troy Elliott told the council Wednesday that the borrowing capacity for the city’s next bond election is roughly $625 million — up slightly from the $500 million projection he made in August, but a far cry from the $1.2 billion bond the city was able to pursue in 2022.

That’s money used to fund everything from drainage to libraries, but in the case of the next bond election in 2027, is expected to also cover roughly $250 million worth of infrastructure related to Project Marvel.

“When Troy announced this number of $500 million [in the last forecast], I don’t think my jaw was the only one that dropped,” said Mayor Gina Ortiz Jones, who has been on a lonely quest to slow the finalization of sports district agreements until city leaders could assess them within the context of a broader financial outlook.

“When we consider what our bond capacity has traditionally been … This number is really going to call for us to be thoughtful about how we identify and then prioritize those needs across the city.”

Betting on growth

San Antonio funds most of its infrastructure projects through money that’s borrowed against the city’s future growth and repaid through the debt service portion of the property tax rate.

The other portion of the tax rate, known as maintenance and operation, funds day-to-day general fund expenses like salaries and programs.

In years of skyrocketing property valuations, the city was able to craft its spending in both categories around what it expected to take in, using data from the appraisal district to design a budget that met the state’s 3.5% growth cap on existing properties.

Now that revenue is coming in below 3.5% growth, Elliott said Wednesday, the city may consider changing its approach from one that budgets around capacity at the existing rate, to one that identifies its needs and sets a rate to match.

“Historically, our property values have increased over time, on average about 6% over 20-plus years,” Elliott told the council.

The city already lowers its tax rate in years where it has to shed revenue to stay within the state’s growth cap. By adding the flexibility to bring it back up in years of slower growth, Elliott said, the council could keep its revenue growth on a more predictable trajectory, and borrow based on historical trends rather than moment-in-time data.

He presented several options for how that might look in the next bond election, with one allowing the city to pursue another $1.2 billion worth of projects in 2027, if it assumes the maximum 3.5% growth starting in 2028.

The city is currently only projecting its growth to be at 1.75% two years from now — something that could easily change in either direction.

But adopting the 3.5% growth assumption means council could raise the revenue without seeking permission from voters if it had to — they’d just have to break a three-decade streak of keeping an even or lower rate.

“When you look at the needs in the community in terms of infrastructure, streets, our drainage, our buildings, our facilities … This provides you an alternative … that hopefully provides a little bit of balance between the size of our bond programs and investments in our community and the tax rate,” Elliott said to the council.

City leaders laid out ways the council could pursue a larger bond in 2027, but noted doing so could require raising taxes if economic growth doesn’t bounce back in the next two years. Credit: City of San Antonio

City leaders laid out ways the council could pursue a larger bond in 2027, but noted doing so could require raising taxes if economic growth doesn’t bounce back in the next two years. Credit: City of San Antonio

A divided council

A potential rate hike vote is still far off, but Wednesday’s meeting offered an early look at the council’s reaction to major spending decisions coming down the pipeline.

Faced with a budget shortfall last year, the council overwhelmingly supported addressing it with cuts and free adjustments instead of raising the tax rate.

Now that the conversation has turned to infrastructure, however, members from historically underserved parts of the city were reluctant to delay investments in flood safety, pools and other amenities, while those representing wealthier Northside districts wanted the city to stick to its guns on not raising the rate.

“Traditionally, we were red-lined, we were forgotten, and we are still trying to make up for the street improvement we need, the drainage, the sidewalks, the flood mitigation,” said Councilwoman Phyllis Viagran (D3), who represents part of the South Side, and was one of several members to raise concern about urgent flood safety issues in her district.

Councilman Marc Whyte (D10), meanwhile, said the city should make cuts to its general fund to fix urgent safety needs it can’t cover through the bond, and put the rest off until later.

“It’s really unfathomable to me that we would be sitting here today talking about raising the tax rate on our citizens when no mayor or City Council has raised this rate on the citizens [in decades],” said Whyte, who represents the North Side.

Other colleagues called that approach unrealistic, given the cost of such projects and the salary-heavy city budget. Jones compared it to the city-owned water utility, which is gearing up to ask for a rate increase, she said, because it put off projects it should have done sooner.

“The SAWS story is really a story of delayed maintenance,” she said. “They kicked the can down the road, now we are paying for that, and unfortunately, we’re paying it at a time of tariffs, higher labor costs, etc. So we recognize the risk of continuing to delay these things.”

San Antonio Mayor Gina Ortiz Jones listens to a presentation on the Sports and Entertainment District project from the city’s chief of financial and administrative services during a B Session council meeting at City Hall on Jan. 14, 2026. Credit: Amber Esparza / San Antonio Report

San Antonio Mayor Gina Ortiz Jones listens to a presentation on the Sports and Entertainment District project from the city’s chief of financial and administrative services during a B Session council meeting at City Hall on Jan. 14, 2026. Credit: Amber Esparza / San Antonio Report

A focus on flooding

Flood mitigation is top-of-mind to many council members after an exceptionally deadly summer, and while a tax rate increase remains controversial, city staff presented another route to fund those projects through raising the city’s stormwater fees — something members generally seemed to support.

“[When] we keep pushing off the stormwater fee increase … more of our residents find themselves on the FEMA flood map, and so they end up having to pay a ton of money in flood insurance,” said Councilwoman Marina Alderete Gavito (D7). “I think it’s incumbent on us as a city to try to mitigate that as best as possible.”

But much of Wednesday’s meeting was aimed at laying out the options for timing and structure of the next bond election, which is now likely to come sometime in 2027.

Faced with the prospect of Project Marvel edging out flood control projects in that process, a group of council progressives said they didn’t want the sports and entertainment district infrastructure to be looped in with the rest of the city bond on a single ballot proposal.

Councilwoman Teri Castillo (D5), who voted against the Spurs’ term sheet in August, said her constituents worried about “the overall impact that the potential sports district is going to have on increasing property taxes all throughout the city,” and want that piece to be its own vote.

Councilman Edward Mungia (D4), who supported the term sheet in August, seconded that idea, saying the Project Marvel component should even have a separate public input process from the rest of the bond.

“Any sort of sports-related or entertainment district bond has to be a completely separate bond proposition,” he said.

Jones, in recent months has had little luck rallying colleagues around her skepticism of the sports and entertainment district, closed out the meeting saying that there are still many pieces to fall in place in terms of city finances before a bond proposal goes out to voters.

Federal cuts are coming for SNAP, Medicaid and CHIP. Both city-owned utilities want rate increases. And, the council still has a major budget gap to address in fiscal year 2027, she said.

“For those folks who say, ‘How much is too much?’ That’s why you do the due diligence before you sign the community up for $489 million,” she said, referring to city’s contribution to the NBA arena. “[It’s also] why it’s important that we give people a say in whether or not some of these projects go forward.”