Just after 7 Thursday night, the Rev. Mitchell Boone, the young, bespectacled senior pastor at downtown’s First United Methodist Church, took his place behind the pulpit. He was there to welcome people to the Point in Time Count, that one night of the year when volunteers spread across the city to find, question and count the unsheltered.

Or, as Boone put it, that moment when we head into the darkness to find “common humanity in our unsheltered neighbors.”

I was reminded of that quote a couple of hours later, when I was in the miles-long Joe’s Creek storm drainage channel that runs beneath Harry Hines Boulevard in northwest Dallas. All day and night, there’s a steady stream of people walking down or coming up from an entrance to the channel near the Anchor Motel and Underwood Mobile Home Park.

Deputy Mayor Pro Tem Gay Donnell Willis, one of four Dallas City Council members taking part in the count, was talking to a woman in a pink tent pitched a few hundred yards from Harry Hines, just above the drainage ditch full of trash, a dead raccoon and streaming water. There were two other makeshift structures nearby. The woman unzipped her tent just enough to let us see her eyes.

The council member crouched down. “Do you know about the bad weather coming?” Willis asked her, hoping to persuade the woman to take shelter at Fair Park or elsewhere. She didn’t respond, so Willis tried asking her some of the questions from the official questionnaire volunteers are given to complete the count.

Opinion

“How old are you?” Willis asked.

“46,” the woman said.

“What’s your ethnicity?”

The woman didn’t answer for a few seconds, then said, “Human.”

Said Willis, “That’s fair.”

Willis thanked her and went back to join some volunteers interviewing folks camped nearby. The woman told me she’d been out here 20 years, on and off. She said was used to the blazing hot and the bitterly cold. I asked if she needed anything.

“Yeah,” she said, laughing. “Another blanket.”

Point in Time Count volunteers interviewed people living in an encampment off Joe’s Creek Thursday night.

Robert Wilonsky

Used to be, when we had a serious, functioning federal government, the Department of Housing and Urban Development used the count’s numbers to figure out where and how best to spend grant dollars. These days it’s more of a snapshot of where things stand with those who sleep outside and in the overstuffed shelters. “To measure trends,” said a rep from Housing Forward, which oversees the count in addition to efforts to find roofs for those without them in Dallas and Collin counties.

In the past couple of weeks, Housing Forward has persuaded the city and Dallas County to kick in $10 million, each, to expedite finding homes for the homeless. The shelters are full; there’s no room in the inn. It seems unsustainable having to beg each year for money the current federal administration keeps fighting to withhold from organizations working to shelter the vulnerable.

“When we offer people a pathway off the street, 95% say yes,” Sarah Kahn, Housing Forward’s president and CEO, told me earlier this week. “With inclement weather shelters, there’s a variety of reasons they don’t come in, but generally, people want to go in, and there’s just not a bed available.”

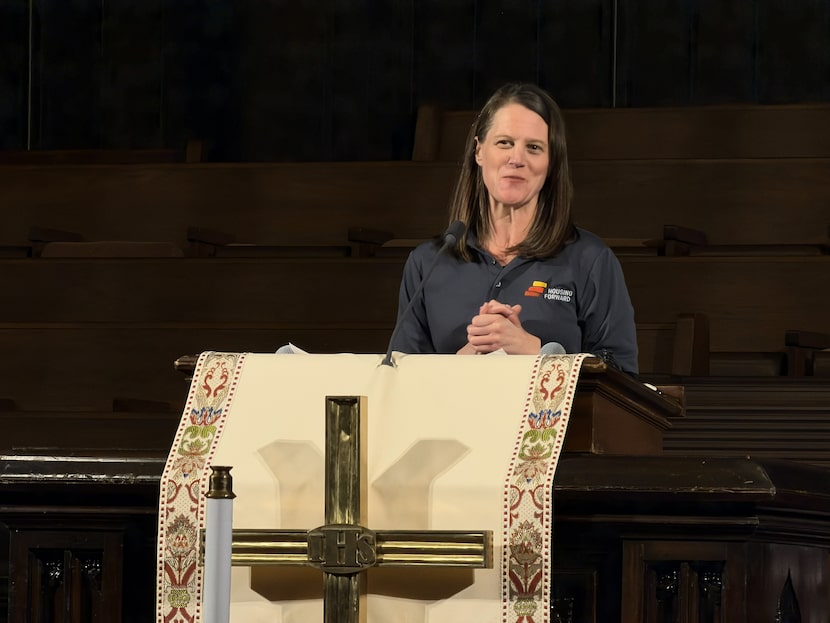

Sarah Kahn, president and CEO of Housing Forward, at the First United Methodist Church pulpit Thursday night, addressing volunteers about to head out for the annual Point in Time Count.

Robert Kent

Willis, the deputy mayor pro tem, showed up Thursday night despite having previously canceled her RSVP. Later that night, when we were standing in a busy northwest Dallas convenience store parking lot, she told me, “I feel obligated to be here,” in part to warn people of the single-digit temperatures and ice expected to shroud the city this weekend.

“It’s literally a matter of life or death,” Willis said.

Down in the canal we met a woman named Isabel, 51 years old and San Antonio born, who was missing most of her teeth. Said she’d been homeless for 10 years, since a daughter died. Of late, she’s been sleeping out in the open without so much as a blanket to keep her warm. “I use my coat,” she said, clutching a worn blue peacoat thrown over a few other layers. She knew nothing about the coming cold.

A few volunteers asked Isabel questions from the census, about whether she had a substance abuse problem, about whether she was running from domestic violence, about whether she had mental health issues. Yes, no, and yes. Which is why she can’t keep a job, she said, or find a place to stay.

Yolanda Williams, director of grants and contracts at Housing Forward, joined a group of volunteers heading into Joe’s Creek for Thursday night’s Point in Time Count.

Robert Wilonsky

Isabel, quiet and kind as she answered every question, mentioned she has a son and a daughter who live in Farmers Branch. A volunteer begged her to stay with them this weekend. Isabel said she hadn’t spoken with them in two years.

Yolanda Williams, Housing Forward’s director of grants and contracts, was among our small band of counters. I told her I’m always amazed by how eager the unsheltered are to share their stories.

“They just want to be heard,” said Williams. “They just want to be seen.”

It had taken a while to find folks. But, suddenly, they seemed to be everywhere in the easement between Brockbank and Denton drives, between an apartment complex and a noisy, well-lit warehouse where workers were hauling metal frames used in commercial construction.

There were tents full of people, many in their 20s. Some sat by a campfire smoking cigarettes beneath the balconies of the apartment complex on the other side of a rickety wooden fence. Others congregated by the canal, uninterested in being interviewed for the Point in Time Count.

A 26-year-old man, his face obscured by a mask and a parka hood pulled tightly over his head, said he just got out of jail and was hoping to get back his old job at a McDonald’s. Men and women came and went from his tent as we spoke. I asked if they were going to take up the city’s offer of a warm shelter before the ice and cold got here.

“I know how to handle my business,” was all he’d say.

Dallas City Council member Gay Donnell Willis tried to convince a 51-year-old, who said his name was Mauro, to take refuge in one of the city’s shelters this weekend.

Robert Wilonsky

On the warehouse side of the canal, a 51-year-old man named Mauro had constructed a wood-frame box wrapped tightly with a black tarp. Over the loud, constant din of machines moving metal, he said he’d been here three years and that he wasn’t inclined to leave this weekend.

“I’m a little worried about you,” Willis told him.

He waved her off. “It’s weather,” the soft-spoken man said from beneath his tall knit cap.

A 48-year-old woman named Stefani emerged from Mauro’s blue structure, and told us she’d lost her job at Michael’s during COVID and has been out here ever since. She’s been moving from structure to structure, she said. “Somebody brought me here,” Stefani said. She pointed to Mauro and said he was kind. “My protector.”

Our large group disbanded once we left the canal, with smaller groups decamping for areas around Dallas Love Field and along Stemmons Freeway. A few of us ended up at the busy Lombardy Lane and Brockbank Drive intersection, where we met a man named Jabari who turns 25 next month. He said he was from Greenville, Miss., but moved to Plano to live with cousins. That was before everything in his life fell apart.

An apartment complex looms over an encampment in northwest Dallas. It’s well-lit because there’s a warehouse on the other side.

Robert Wilonsky

As we spoke, a young Hispanic man approached with a heavy comforter he wanted to give to Jabari, who was touched by the gesture. “First time anyone’s given me anything out here,” he said, fussing with the fidget spinner in his right hand.

I mentioned that Isabel had told us about a woman in a wheelchair who lived with a dog behind the convenience store at this intersection crowded with Mexican restaurants, liquor stores and vape shops. He knew who I meant, because everybody knows everybody around here.

He took us to meet a 54-year-old woman who told us to call her Mama. She was sitting on the cold pavement along a side street off Lombardy. Next to her was the wheelchair she has used ever since she was hit by a car, she said. She was accompanied by a little white dog she called Coyote. A deaf man, wearing thick glasses and a reflective vest, stood nearby. Mama said he was her friend and bodyguard.

Mama said she’d just spent 10 days in Dallas County jail for criminal trespassing. She said she’d welcome a few days in a shelter, but had trouble getting in one because someone had stolen her duffle bag containing all of her documents.

One of the volunteers handed her a bag containing hand warmers, a knit cap, gloves and other cold-weather necessities for which she was grateful. Another, named Ashley, texted Our Calling and told them where Mama was — sitting on the cold pavement next to a cardboard box filled with everything she owns in the world. Ashley told Mama that a green van would be by in the next day or so to ferry her and the dog and her friend somewhere warm.

“Bless you,” Mama said as we walked off.

“This is life and death, what’s coming,” Willis said in the parking lot before we parted. “But in a crazy way, the weather is our friend. Being out here tonight, maybe we get them in shelter, and then they have a shot at getting reconnected.”

With help, yes. But with a little humanity, too.