The announcement last month that Occidental Studios would be put up for sale marked a historic turning point in a studio once used by Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks to make silent films.

It also underscored how dramatically the market has shifted for the owners of soundstages across Los Angeles that have been buffeted by a confluence of forces — the pandemic, strikes in 2023 and the continued flight of production to other states and countries.

As film activity has fallen to historic levels in the L.A. region — film shoot days dropped 22% in the first quarter of 2025 — the places that host film and TV crews, along with prop houses and other businesses that service the industry, have been especially hard hit.

Between 2016 and 2022, Los Angeles’ soundstages were nearly filled to capacity, boasting average occupancy rates of 90%, according to data from the nonprofit organization FilmLA, which tracks on-location shoot days in the Greater L.A. area.

That rate plummeted to 69% in 2023, as dual writers’ and actors’ strikes brought the industry to a halt.

Once the strikes were over, production never came back to what it was. In fact, last year the average occupancy rate dropped even further to 63%, according to a FilmLA report released in April.

So far this year, there is “no reason to think the occupancy numbers look better,” said Philip Sokoloski, spokesperson for FilmLA.

“It’s a trailing indicator of the loss of production,” he said. “The suddenness of the crash is what caught everybody by surprise.”

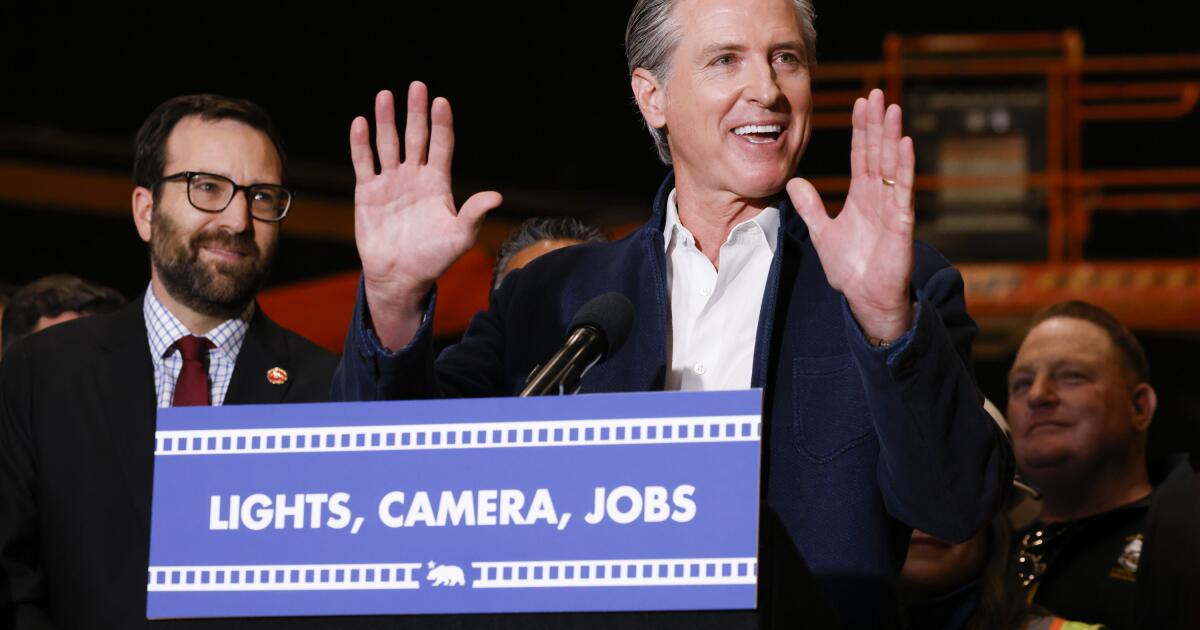

Studio owners, who have watched their soundstages go from overbooked to frequently empty, are celebrating the new state tax credits meant to boost their industry and create action on their lots.

The California Legislature’s decision to more than double the amount allocated each year to the state’s film and television tax credit program to $750 million could be a tipping point toward better times, studio owners said, but the climb out of the doldrums is still steep.

“This is definitely a defining moment and to see whether or not L.A. is going to get itself back up to the occupancy levels that it had prior to COVID,” said Shep Wainwright, managing partner of East End Studios. “Everyone’s pretty bullish about it, but it’s obviously been such a slog for the past few years.”

Sean Griffin of Sunset Studios called the tax credit boost signed into law last week “a massive stride in the right direction” while Zach Sokoloff of independent studio operator Hackman Capital Partners called the decision “an enormous win for the state.”

Sokoloff hopes to see its Southern California facilities, which include Radford Studio Center and Culver Studios, perk up the way their New York properties did when the state increased its film and TV subsidy to $800 million in May.

“We had stages that had been sitting empty, and almost 24 hours after the passage of the tax credit bill in New, York, our phones were ringing,” he said. “We had renewed interest in soundstage occupancy there.”

Community member William Meyerchak, left, Los Angeles City Councilmember Katy Yaroslavsky, center, and Zach Sokoloff, senior vice president of Hackman Capital Partners, right, celebrate after the passing of the $1-billion TVC project, which will expand and redevelop the old CBS Television City site at Beverly Boulevard and Fairfax Avenue, on Jan. 7, 2025.

(Christina House / Los Angeles Times)

Los Angeles Center Studios, where such shows as “Mad Men” and “Westworld” filmed, also has felt the effects of the production slump.

The 26-year-old facility in downtown L.A. has six 18,000-foot soundstages and three smaller stages, along with a number of practical locations on the lot for shooting. Before the pandemic, its stages were 100% full for more than 10 years, said Sam Nicassio, president of Los Angeles Center Studios.

He declined to state the studio’s current occupancy rate, though he said it was above the average for about 300 soundstages throughout the area, which his company tracked at 58%.

“It’s been a struggle,” he said. “The slowdown in overall production activity, coupled with coming out of the strikes and all of us expecting to have a jump-start again and we didn’t, was very difficult. There’s a lot of soundstages for not a lot of users right now.”

Not long ago, private equity firms saw L.A. studio stages as good business opportunities.

A billboard for a Netflix streaming show “The Diplomat,” on a building across the street from where WGA members walk a picket line around Bronson Sunset Studios, in May 2023.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

WGA members walk a picket line around Bronson Sunset Studios lot, where Netflix leases space for production and offices, in May 2023.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

A number of firms participated heavily in the construction of new facilities, which seemed like smart bets due to advancements in production technology, the desire of studios and streamers to cut down on unpredictable risk from on-location shoots and — especially after the pandemic — health and safety systems like air filtration and more space to prevent workers from getting sick.

“Stages are critical to being able to do, especially TV, on time and on budget,” said George Huang, a professor of screenwriting at the UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television. “They are the backbone of making movies in Hollywood.”

But after the pandemic, strikes and a cutback in spending at the studios, production slowed. Then in January, the Southern California wildfires hit, further affecting production and causing many in the industry to lose their homes — and reconsider whether they wanted to stay in the Golden State.

Working with influencers

As Hollywood production slowed, soundstage operators looked for new ways to make up revenue, including shoots for the fashion industry, music videos, DJ rehearsals, video game production and even private events like birthdays or weddings.

Hackman Capital Partners, which owns and operates Television City in Los Angeles, recently announced a partnership with Interwoven Studios to open a boutique production facility catering to social media influencers, online media brands and other creators who work in nontraditional formats such as YouTube.

Among the well-known creators who have worked lately at Television City — home to such classic shows as “All in the Family” and most recently “American Idol” — are Logan Paul and Jake Shane, actress-singer Keke Palmer, livestreamers FaZe Clan and hip-hop artist Big Sean.

“As the segment of the content-creation universe grows on the smaller end of production, we’re going to be a partner to them,” Sokoloff said. “Necessity is the mother of invention.”

Sunset Studios, which operates 59 stages in the Los Angeles area, has long made a point of working with short-form creators through its smaller Quixote division, said Griffin, who is head of studio sales. “We’ve always been involved with influencers, music videos and commercials.”

Such tenants working on smaller stages sometimes move up to TV and movie-sized stages when they land a big television commercial or music video, such as Selena Gomez’s “Younger and Hotter Than Me” music video recently shot at Sunset Las Palmas Studios.

Paul McCartney leased a studio at Sunset Glenoaks Studios to rehearse for his 2024 tour and and made a music video there.

In general, though, stages are still underused, he said.

“Once the strikes ended, we got a about a good healthy quarter” of production, he said. Then business “really quieted down, and we haven’t seen the show counts rebound very much.”

The vacancies have created a tenant-friendly market as studio owners compete for their business on rental prices, Griffin said.

“This is a very tough market,” he said. “Everyone is competing very, very hard.”

One reason for optimism about the new tax credits is that they apply to 30-minute shows for the first time, he said.

“L.A. is a television town,” Griffin added. “Opening up the tax credit to 30-minute comedies is going to be really helpful.”

And there are signs of life for longer scripted shows that take multiple stages and shoot for longer than other productions, Griffin said.

Developer David Simon is betting heavily on a turnaround. He is building a new movie studio from the ground up in Hollywood. His $450-million Echelon Studios complex is set to open late next year on Santa Monica Boulevard.

“We think content creation is here to stay in various forms,” he said, and that big soundstages will continue to be used even as the technology to make content changes.

Simon said he is close to signing leases with fashion brands that are creating content with celebrities and collaborating with influencers.

“We’re not nearly where we were prepandemic,” he acknowledged, but “California is the entertainment capital of the world, and the producers and directors and actors that want to stay in state will help bring back and retain our fair share of production.”

For now , at least, soundstage operators are still “treading water,” said Peter Marshall, managing principal at Epic Insurance Brokers & Consultants, who works in media insurance and counts some L.A.-based soundstages as clients.

“Most operators are pretty concerned,” he said.

Yet, the fact that there are still new soundstages opening and others are in development suggests a “high level of confidence” that production will eventually return to L.A., Sokoloski of FilmLA said.

“I am optimistic that we will keep more production here than we have in the last few years,” Nicassio said. The new tax credit program “puts us on a competitive level now with other states and countries.”

Others in the industry say that more is needed and have advocated for a federal tax credit that would help make California a morecompetitive location. Gov. Gavin Newsom has pushed for the idea, urging President Trump to work with him on the issue.

“When you have a governor and big private equity firms both focusing on promoting one thing, that might, who knows, get the federal government involved,” Marshall said. “That would be the game changer.”