Dogs, bikes and belongings lay on the sidewalk after being hastily moved out of the targeted zone during a sweep of the homeless encampment near 8th and Harrison streets on June 4, 2025. More recently, health officials have said they detected an outbreak of leptospirosis in the camp. Credit: Adahlia Cole for Berkeleyside

Dogs, bikes and belongings lay on the sidewalk after being hastily moved out of the targeted zone during a sweep of the homeless encampment near 8th and Harrison streets on June 4, 2025. More recently, health officials have said they detected an outbreak of leptospirosis in the camp. Credit: Adahlia Cole for Berkeleyside

City and county health officials’ detection of a leptospirosis outbreak in and around a longstanding Northwest Berkeley homeless encampment has many in the neighborhood worried about what it means for them and their pets.

Veterinarians found leptospirosis in two dogs within the encampment around Eighth and Harrison streets, both in November, one of which died, and later detected the illness in rats for the first time in five years in Alameda County.

As of the Jan. 12 announcement there were no known human cases. City officials did not respond to Berkeleyside’s inquiries, sent Thursday, as to whether that has changed. County officials said that they are continuing “to monitor the area and trap rats,” and “to provide support to the residents of the encampment on their rodent issues.”

The bacterial pathogen, rare in the developed world, is treatable with antibiotics, and there are vaccines for dogs and other animals.

Berkeleyside has compiled some information on the disease and its risks from public health and veterinary medicine experts, as well as city health officials.

Just how dangerous is leptospirosis?

According to the CDC there are only about 1 million human cases of leptospirosis a year, most of those in developing countries and primarily in tropical climates, since the bacterium thrives in wet environments. Of those cases about 60,000 end up becoming fatal. In 90%of cases, humans and animals recover without any treatment, according to a study in the National Library of Medicine.

However uncommon in the United States and other wealthier countries, untreated cases of leptospirosis can lead to kidney and liver failure, meningitis and death. And because it is so rare, and its symptoms so common to other illnesses, doctors and veterinarians sometimes do not think to look for it.

“Most people who are exposed don’t get it — only about 10% get symptoms,” Dr. Peter Chin-Hong, a professor of medicine and infectious disease specialist at the University of California, San Francisco, told Berkeleyside in a phone interview. And of that 10% who develop symptoms, only 10% — or about 1 in 100 people exposed — develop severe symptoms, Chin-Hong said.

The illness can be more dangerous to people who are immunocompromised or have diabetes, liver disease or kidney disease, Chin-Hong said.

In pregnant people the bacterium can pose a deadly risk to fetuses, according to the CDC.

Who can catch leptospirosis, and how?

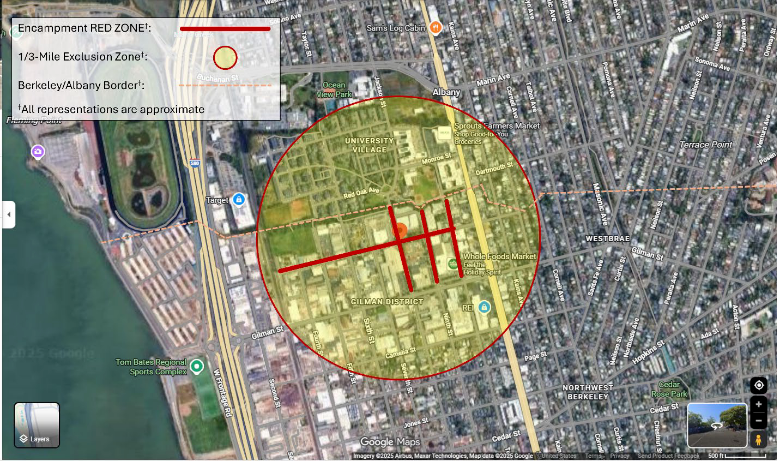

A map from Berkeley health officials puts the epicenter of the outbreak at Eighth and Harrison streets. The “red zone,” or most at-risk parts of the neighborhood, are Harrison Street from Cedarwood Lane to 10th Street and two blocks each of Eighth, Ninth and 10th streets, one each on either side of Harrison.

Health officials have recommended people take precautions if they pass within 1/3 of a mile of the outbreak’s epicenter, at Eighth and Harrison streets. Credit: City of Berkeley

Health officials have recommended people take precautions if they pass within 1/3 of a mile of the outbreak’s epicenter, at Eighth and Harrison streets. Credit: City of Berkeley

In a lower-risk “yellow zone,” radiating out ⅓ of a mile from Eighth and Harrison, “there is no evidence of active transmission of leptospirosis or of unmitigated rat populations,” according to the Jan. 12 announcement. “However, proximity to the encampment red zone creates risk and need for prevention efforts.”

Leptospirosis is zoonotic — meaning it can jump between species — but is not airborne, and not transmitted by coughing or sneezing. The most common route of transmission is by way of urine from infected animals, either directly or by way of contaminating water or mud. If animals drink contaminated standing water, or if the bacterium comes in contact with cuts or mucous membranes (eyes, mouths, noses) on people and animals, they can contract the disease.

The illness can spread by bites that break skin, or pass from infected mothers to their young. The bacterium can also linger on plants that have come into contact with contaminated water or mud, making it prudent to wash anything harvested in contaminated areas. While the bacterium can persist for months on end in contaminated water, it typically dies off when puddles and pools dry out, and is susceptible to disinfectants and heat over 112 degrees Fahrenheit.

Wild animals that come into contact with the bacterium are at risk, but dogs are generally regarded as the most common domesticated animal to contract it.

Cats, too, can contract leptospirosis, though compared with dogs, frequently show much milder symptoms or no symptoms at all. But while the illness might not hurt a cat directly, an infected cat can continue to shed the bacterium for years, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Leptospirosis can also spread to livestock and marine mammals. Sea lion populations along the California coast generally see surges of the illness every three to five years, though there was an unexpected surge in cases this summer, KTVU reported at the time.

How do I prevent transmission?

While there is no human vaccine, there is a canine vaccine for leptospirosis — an initial series of two shots followed by annual boosters. There are also vaccines for cats, cows, goats, sheep, pigs and horses. The CDC recommends vaccinating all animals possible “even if they get leptospirosis because the vaccine might cover different strains, and it may help avoid more severe disease.”

Chin-Hong said folks passing through the area should cover open wounds and take other common-sense precautions like washing hands, but “people don’t have to worry about casual pedestrian exposure.”

While people probably should not wade into the creek, nor play in puddles, “I think they don’t have to worry about it too much, not to be too panicked about it.”

For unhoused people living in the area, the greatest risk is to their dogs. Chin-Hong recommended they keep their pets leashed, get pets vaccinated where possible and use hand sanitizer if and when running water is not available to clean and disinfect.

What are the symptoms and treatment for leptospirosis for humans, dogs and cats?

The most prominent signs that dogs are infected are fever, muscle tenderness and lethargy, according to the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA). “Other signs may include loss of appetite, vomiting, diarrhea, jaundice … inflammation of the eyes, bloody nose, urine or stool and changes in the amount and frequency of urination,” according to the organization’s page on the illness.

In humans, the bacterium brings on fever, headache, chills, body aches, jaundice, red eyes, stomach pain, rashes, vomiting, nausea and diarrhea, according to the CDC. Because so many of these symptoms mimic other illnesses, leptospirosis is frequently mistaken for something else, and some people never show symptoms at all, according to the agency.

Humans generally become ill sometime between two and 30 days after contact, though symptoms most commonly present five to 14 days after exposure, according to the CDC. Patients typically experience flu-like symptoms in the first phase of illness, but may also enter a second, more severe phase that could bring on kidney or liver failure or meningitis, or inflammation of the membrane around the brain and spinal cord.

Doctors and veterinarians can test for leptospirosis in patients’ blood and urine. In humans and animals, the disease is treatable with antibiotics. Some veterinary experts warn that early detection is crucial in dogs to prevent permanent liver or kidney damage.

Chin-Hong said that because leptospirosis is so rare and difficult to diagnose, it might fall to patients or pet owners to bring it up with doctors and veterinarians.

What guidance does the Berkeley health department give?

The Berkeley Health, Housing and Community Services Department has issued a series of recommendations for those who live, work or visit in the area that may be contaminated:

- If you are camped in the area, move at least a third of a mile away

- RVs and other vehicles with long-term rat infestations should be destroyed

- Clean all “non-porous” property — bicycles, tools, hardware and so on — by removing all visible mud and debris with soap and water and then disinfecting with a 10-to-1 bleach-water solution, leaving it on for at least 10 minutes

- Destroy any “contaminated soft goods” like blankets or tents that have been on the ground

- Throw out any food, beverages or water with which rats may have come into contact

- If coming into contact with mud or standing water in the encampment, or with items that were previously exposed to them, wear masks, waterproof boots, eye protection and nitrile or rubber gloves; do not let mud, runoff or water touch skin, mouths, noses, or eyes

- Treat creek water, puddles and any other standing water in the area as contaminated; do not walk or bike through standing water or the creek

- Vaccinate dogs and free-roaming cats; keep pets on short leashes; bring water for walks and do not let pets drink from other sources

- When gardening, wear gloves and protective foot coverings

- Wash any fruits and vegetables harvested in the area before consuming

- If you think your pet has been exposed to leptospirosis, or is showing signs of illness, contact your veterinarian immediately

“*” indicates required fields