What kind of downtown does Dallas want to build for the next 50 years? The answer to that question should guide every decision about the future of City Hall and the land around it.

A truly successful City Hall district is one where public investment and private development work together; where civic institutions, sports and entertainment, housing, hotels and everyday businesses reinforce each other instead of competing for the same ground.

Dallas is standing at a crossroads. Powerful interests are urging the city to walk away from the City Hall building, owned free and clear by the taxpayers, and raze it for a new arena and private development. These interests frame the building as outdated, inefficient and too expensive to fix. But the numbers tell a different story. When the full costs of relocation, new construction and lost civic value are weighed against reinvestment in the existing building, keeping and renewing City Hall is not only culturally wiser, it is also fiscally smarter for Dallas residents.

Critics are not wrong about the current experience of many visiting and working in City Hall. After nearly 50 years of piecemeal modifications, it can feel unfriendly, hard to navigate, difficult to park and enter, and disorienting once inside. Those are real problems, but they are problems that can easily and affordably be addressed through reconfigured entries and lobbies, clearer wayfinding, modernized interiors and a reimagined public realm around the building.

Opinion

City Hall has been treated as a problem rather than a place to be reimagined. The better vision is to keep it where it is, renew it and make it the civic anchor of a vibrant sports, entertainment and cultural district that finally works for the people who live and work in Dallas as well as those who come to visit.

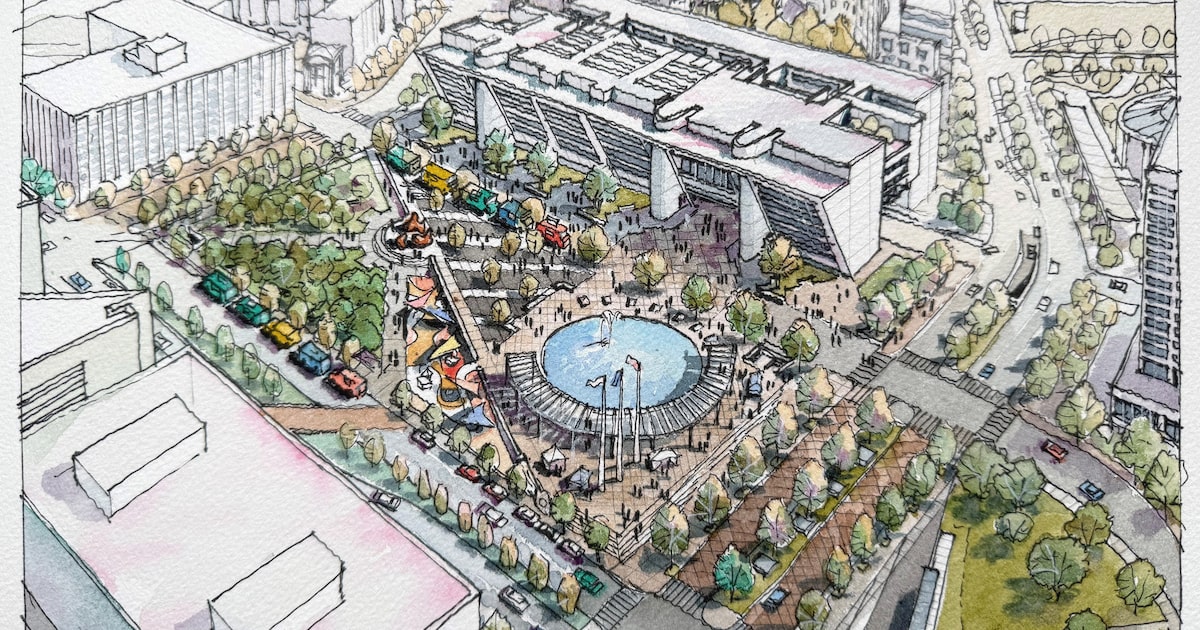

Re-envisioning City Hall begins with reimagining the vast plaza in front of it. Today, it feels more like a windswept concrete podium than a welcoming civic space. Yet it is as big as Klyde Warren Park, which proves how much life and vitality can be created on five acres when a space is shaded, green and properly programmed. City Hall Plaza can become City Hall Park: a place of trees, water, play, performance and gathering that invites people to linger before work, at lunch and into the evening. With cafés and public amenities around its edges, the plaza can shift from empty backdrop to beloved urban living room. City Hall Plaza deserves the same vision and investment given to the downtown parks program.

Some are saying that relocating City Hall functions to the core of downtown would be a catalyst for downtown renewal. This idea continues to be put forth despite the reality that City Hall functions would occupy increasingly obsolete 1980s office space while making access to city government even more difficult.

Downtown must continue to be reimaged as a neighborhood, not just a business district. It needs continued investment in police presence to make it a safe and comfortable experience for residents and workers. Sidewalks, landscape, lighting and street improvements linking our highly successful downtown parks will bring more residents to downtown Dallas. Making downtown a safe, vibrant neighborhood is the path to making it a great place to once again do business. A new City Hall Park should be part of that neighborhood.

Transformation of the plaza and streets around City Hall must be matched by transformation inside the building. Rather than remaining an inward-facing office block, a renewed City Hall can bring more public-facing services and people into downtown.

The long-discussed one-stop permitting center, once imagined in a remote office building along Stemmons Freeway, belongs here, in the heart of the city. By expanding City Hall to the south to include permitting, customer service and innovation functions, Dallas could draw thousands of additional daily users to the district: small-business owners, contractors, homeowners and design professionals who will support restaurants, retail and transit. City Hall can become not just a symbol of government but one of the district’s strongest engines of daily life.

Seen this way, the building’s architecture is not a liability, but a starting point. City Hall’s bold, leaning form has represented Dallas to the world for nearly half a century. It appears in films, photographs and civic imagery because it looks like nowhere else. It was commissioned to signal that Dallas is confident, forward-looking and optimistic. Walking away from that investment now would send a different message: that Dallas is prepared to discard a major civic asset for a single transaction. Repairing and reinvesting in the building, by contrast, would show that the city still sees public architecture as long-term civic investment.

Integrating City Hall into an entertainment district does not mean settling for less economic energy; it means insisting on a richer, more balanced kind of energy.

On the more than 30 acres opened up by the convention center demolition, a new Mavericks arena and mixed-use development could be framed not as a self-contained enclave, but as part of a larger civic district that City Hall helps anchor. A sports-only district built only around an arena risks becoming a place that lights up for games and concerts and goes dark between events. A district that combines an arena with a working City Hall, a civic park, housing, hotels, restaurants and cultural venues has reasons to be busy morning, noon and night. City workers and residents would fill the sidewalks on weekdays; families and visitors would come for parks and cultural events; fans and conventioneers would gather for big nights out. Each layer would support the others with active, new destinations complementing an existing one rather than replacing it.

This re-envisioned City Hall district could do something Dallas has long talked about but rarely achieved: connect. From the new convention center across a greened and activated City Hall Park, through mixed-use blocks that could one day include a new arena, and over a deck park toward the Cedars, the city has the chance to create a continuous, walkable sequence of streets and public spaces to be enjoyed by citizens and convention-goers alike. Instead of a hard edge of freeways and back-of-house loading docks, the south side of downtown could become a stitched-together set of neighborhoods.

In the end, the choice is stark but simple. Dallas can clear away its civic heart to make room for a single project, or it can build a new district around a civic asset that will continue to serve the city long after any lease or ownership deal changes.

With billions already committed to a new convention center and the surrounding infrastructure, the question is whether that investment is oriented around a single use or leveraged to create a balanced district, where City Hall, an arena, housing, hotels and a Cedars deck park all work together.

A well-situated, well-functioning civic center, embedded in a mixed-use convention and entertainment district, is the kind of long-term public infrastructure that will pay economic, social and environmental dividends to the citizens of Dallas for the next 50 years.

Duncan T. Fulton III is co-founder and former CEO of GFF. Tipton Housewright is principal emeritus and former CEO of Omniplan Architects. Zaida Basora is executive director of AIA Dallas and the Architecture and Design Foundation.

We welcome your thoughts in a letter to the editor. See the guidelines and submit your letter here.

If you have problems with the form, you can submit via email at letters@dallasnews.com