Black holes may be invisible, but their influence shapes galaxies, modern technology and humanity’s understanding of its own limits.

That was the message shared last week by Priyamvada Natarajan, a theoretical astrophysicist at Yale University, during a session at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. Natarajan, whose research focuses on cosmology, gravitational lensing and black hole physics, traced how decades of theoretical work on black holes have transformed scientists’ understanding of the universe and quietly underpin everyday technologies.

You may like

Those equations come from Albert Einstein‘s theory of general relativity, which describes how mass and energy curve space and time. While black holes represent the theory’s most extreme manifestation, the same mathematics is essential for calculating the subtle but measurable time differences experienced by satellites orbiting Earth.

Clocks aboard GPS satellites tick slightly faster than clocks on the ground because they are farther from Earth’s gravitational pull. Without correcting for these relativistic effects, navigation errors would quickly accumulate, rendering GPS unreliable.

For much of the 20th century, however, black holes were regarded largely as mathematical curiosities — solutions to Einstein’s equations with no clear observational evidence. That began to change in the 1960s, when astronomers identified Cygnus X-1, a powerful X-ray source that became the first widely accepted black hole candidate.

Astronomers now know that most large galaxies, including the Milky Way, host central supermassive black holes whose masses are closely linked to the properties of their host galaxies.

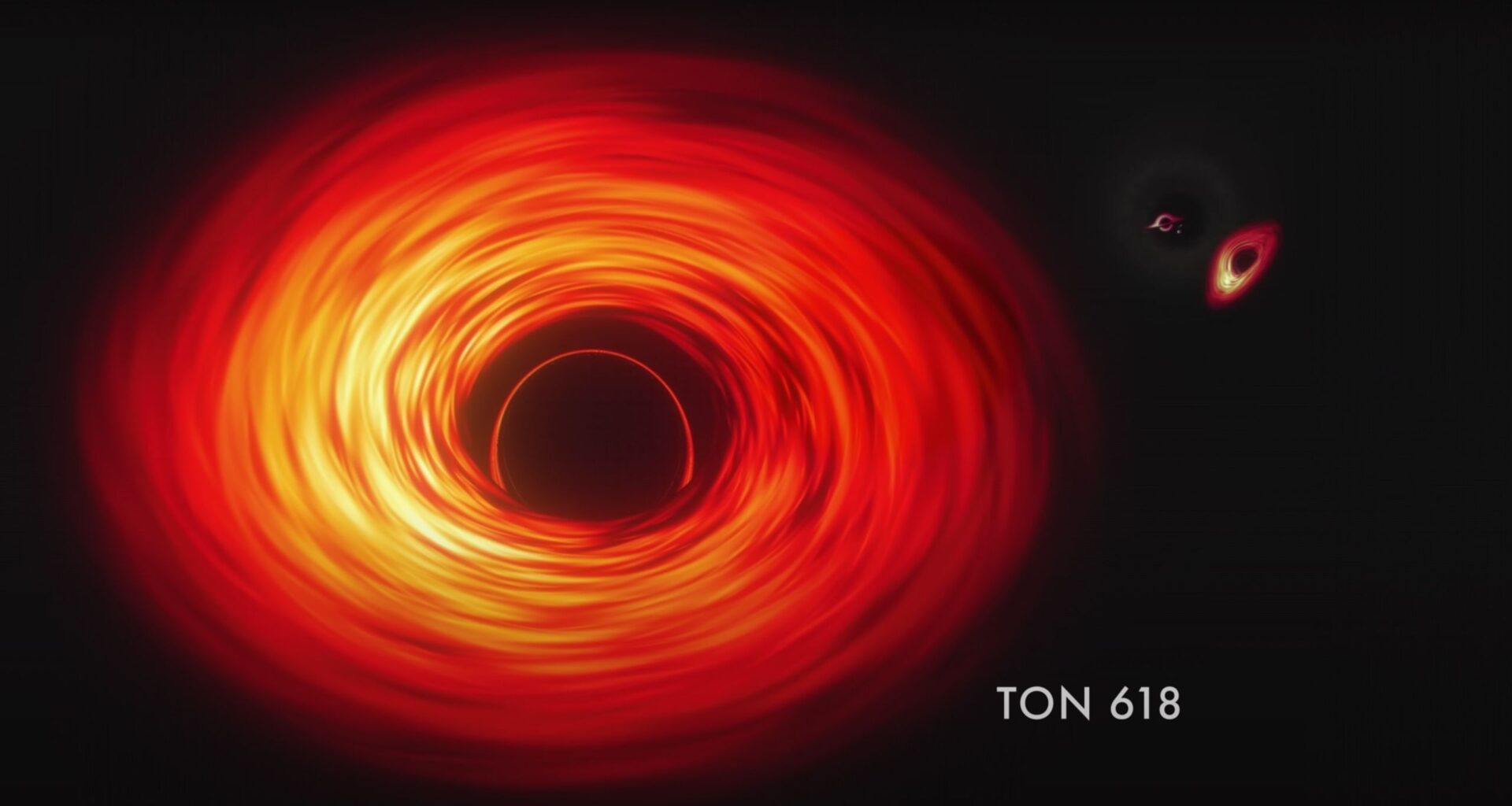

This revised picture, however, has introduced a new puzzle. Telescope observations show that supermassive black holes formed remarkably early in cosmic history, when the universe was only a few hundred million years old. Their sheer size and rapid growth challenge conventional models, which predict that the behemoths grow gradually from the remnants of collapsed, sun-like stars that slowly devour surrounding matter. The origin story of early supermassive black holes therefore remains one of astrophysics’ most persistent questions.

Natarajan and her colleagues proposed a pathway for the universe’s first black holes to form without requiring stars. The team suggested that under specific primordial conditions, pristine gas clouds — which would typically fragment and form stars — instead collapsed wholesale into massive black holes. These objects, known as direct-collapse black holes, would have contained tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of times the mass of the sun within a few hundred million years after the Big Bang. Starting from such unusually large “seeds” helps resolve the timing problem posed by the existence of billion-solar-mass black holes less than a billion years after the universe formed.

Such a system, Natarajan said, would be an “overmassive black hole galaxy whose light is dominated not by the stars but by a black hole that is growing in its center.”

You may like

Her team predicted more than a decade ago that these early black holes would leave distinctive observational signatures detectable by future observatories, including the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and the Chandra X-ray Observatory. In recent years, those predictions have begun to bear out.

One striking example is UHZ1, which reveals that accreting supermassive black holes were already in place just 470 million years after the Big Bang, with masses roughly 10 million times that of the sun.

Another is the so-called Infinity Galaxy, where JWST observations revealed two compact galactic nuclei surrounded by ring-like structures that likely formed via a head-on collision between two disk galaxies. Embedded between them lies a supermassive black hole, not at the center of either galaxy but suspended in a vast reservoir of gas, suggesting it formed through the direct collapse of dense, turbulent gas triggered by the collision.

“It’s a thrill,” said Natarajan, “to be around and, within one career lifetime, to have had the fortune of making predictions that were testable, have been tested, and have been validated.”

Beyond their scientific impact, black holes also carry philosophical weight, she added.

“Studying cosmology in general and black holes specifically really instills a sense of cosmic humility,” Natarajan said.

“Looking out into the universe,” she added, “is uniquely allowing us to look back in time and piece together this beautiful cosmic story that we are part of.”