The next Milky Way supernova may not surprise astronomers at all. According to a recent study available on the arXiv preprint server, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, ahead of its decade-long Legacy Survey of Space and Time, is expected to dramatically improve how quickly and reliably these rare stellar explosions are detected, potentially transforming our view of one of the most violent events in the universe.

A Galactic Event We Know Is Coming, But Rarely See

Supernovae are not speculative phenomena in galaxies like ours. Astronomical theory and external observations leave little doubt that the Milky Way should host core-collapse supernovae on a regular basis. Yet direct human observations tell a very different story. As the researchers behind the new study note,

“Supernovae are observed to occur approximately 1–2 times per century in a galaxy like the Milky Way,” they write. “Based on historical records, however, the last core-collapse galactic supernova observed by humans occurred almost 1,000 years ago. Luckily, we are well positioned to catch the next one with the advent of new neutrino detectors and astronomical observatories.”

That last observed event, SN 1054, left behind the Crab Nebula, a cosmic relic still studied today. Since then, dust, distance, and the structure of the galactic plane have conspired to hide subsequent explosions from Earth-based observers. The new research, titled “Uncovering the Next Galactic Supernova with the Vera C. Rubin Observatory,” argues that this long observational drought is likely to end soon.

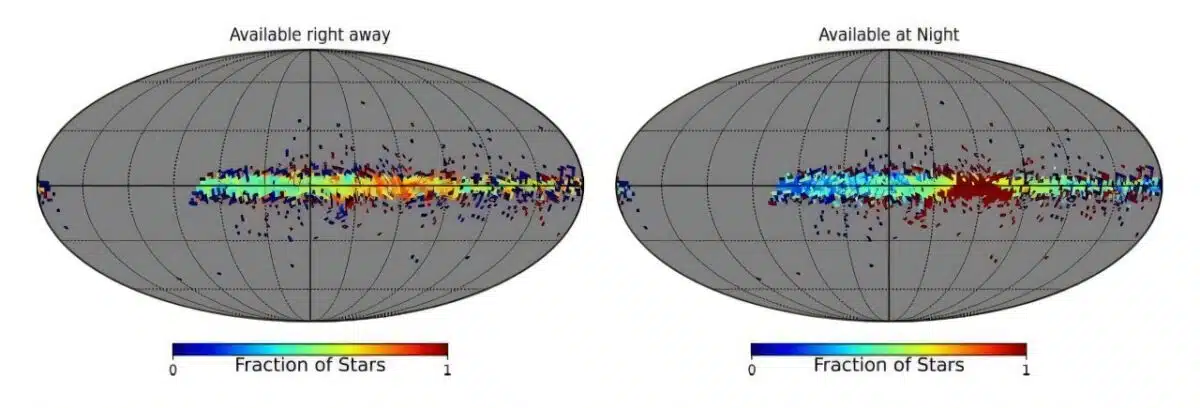

This figure from the research shows the results of placing 100,000 CCSN at a random time of the year and in random locations in the Milky Way. Left: Fraction of stars that explode at night and are available to observe (Available right away). Right: Fraction of stars that explode during the day but are available at night (Available at Night). Credit: arXiv (2026). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2601.12094

This figure from the research shows the results of placing 100,000 CCSN at a random time of the year and in random locations in the Milky Way. Left: Fraction of stars that explode at night and are available to observe (Available right away). Right: Fraction of stars that explode during the day but are available at night (Available at Night). Credit: arXiv (2026). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2601.12094

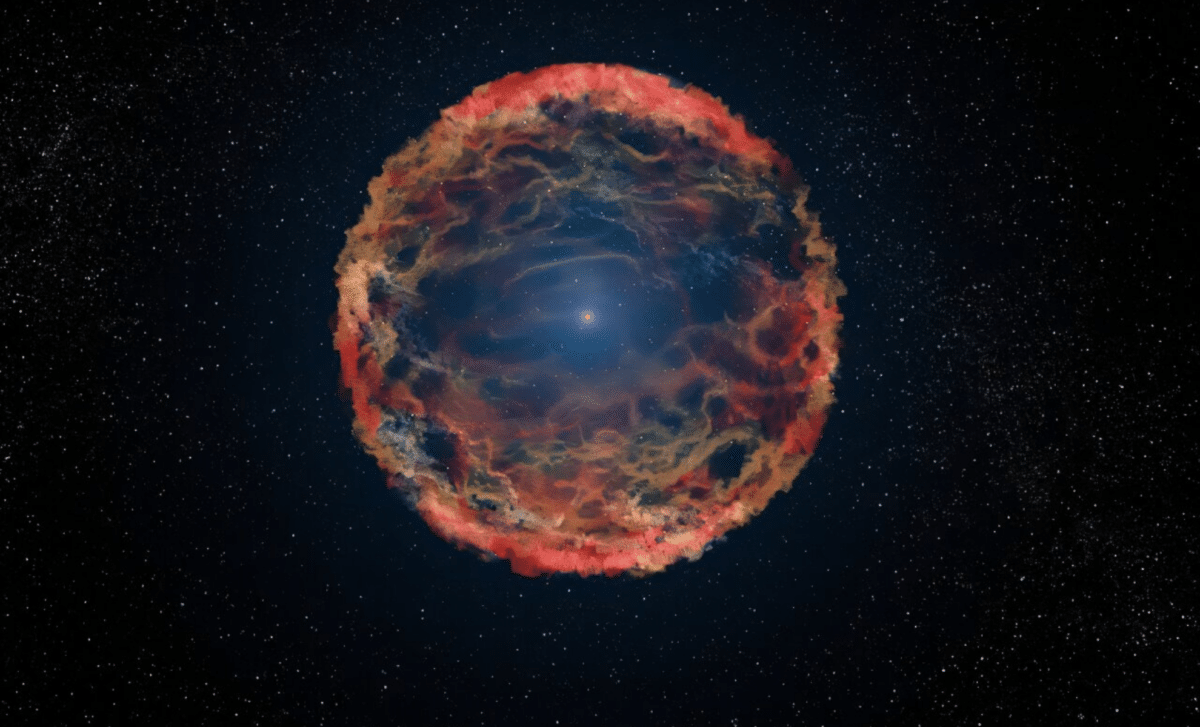

Why Supernovae Matter Far Beyond the Flash of Light

Astrophysicists do not pursue supernovae simply for their spectacle. These explosions are responsible for forging many of the heavy elements that make rocky planets and biology possible. They shape the chemical evolution of galaxies and mark the final step in the lives of massive stars, often giving birth to neutron stars or black holes.

Their extreme environments also function as natural laboratories. Conditions inside a collapsing star push physics to limits that cannot be replicated on Earth, offering rare opportunities to test theories of nuclear reactions, neutrino behavior, and stellar collapse. Each well-observed event refines models of how stars live and die, which feeds directly into broader questions about galactic evolution and cosmic history.

Neutrinos As the Earliest Warning System

One of the study’s central insights focuses on neutrinos, elusive subatomic particles that dominate the energy budget of a core-collapse supernova. While the visible explosion captures attention, roughly 99 percent of the released energy escapes as neutrinos, long before light reaches the surface of the star.

“Neutrino observatories can provide unprecedented triggers for a galactic supernova event as they are likely to see a supernova neutrino signal anywhere from minutes to days before the shock breakout causes the supernova to brighten in optical wavelengths,” the authors explain. “Given its large etendue, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory is ideally positioned to rapidly localize the optical counterpart based on the neutrino trigger.”

This early warning capability allows optical observatories to react with speed and precision. Once neutrino detectors register a burst, Rubin can begin scanning large portions of the sky almost immediately, narrowing down the source before the explosion reaches peak brightness.

Why the Vera C. Rubin Observatory Changes the Game

The Vera C. Rubin Observatory combines a wide field of view with deep, rapid exposures, an unusual pairing in optical astronomy. This makes it especially suited for chasing transient events that appear without warning. In the study, researchers simulated 100,000 core-collapse supernovae distributed randomly across the Milky Way, accounting for dust extinction, distance, and observing constraints such as day and night cycles.

The results point to a major leap in detection capability.

“We find that the observatory is ideal for initial localization of nearly all observable supernova triggers and has a 57%–97% chance of catching any supernova based on theoretical stellar mass density predictions and observations,” the authors write.

Even brief observations matter. A single 30-second exposure in the observatory’s reddest filters may be enough to confirm an event, a critical advantage when minutes can determine whether the earliest phases of an explosion are captured.