Grafting-mediated rescue of nrpd1 pollen defects

Using CRISPR–Cas9, we previously generated a knockout mutant in Capsella rubella NRPD1, in which the induced deletion caused a frameshift and resulted in a truncated protein without the catalytic site22. Loss of Capsella NRPD1 causes pollen arrest at the microspore stage, connected with depletion of 21- to 24-nucleotide siRNAs in microspores22. To test whether the arrest of microspore development in Capsella nrpd1 mutants could be suppressed by non-cell-autonomous siRNAs, we made hypocotyl grafts of Capsella nrpd1 scions to wild-type (wt) rootstocks (referred to as nrpd1s/wtr) and analysed the effect on pollen development and siRNA formation (Fig. 1a).

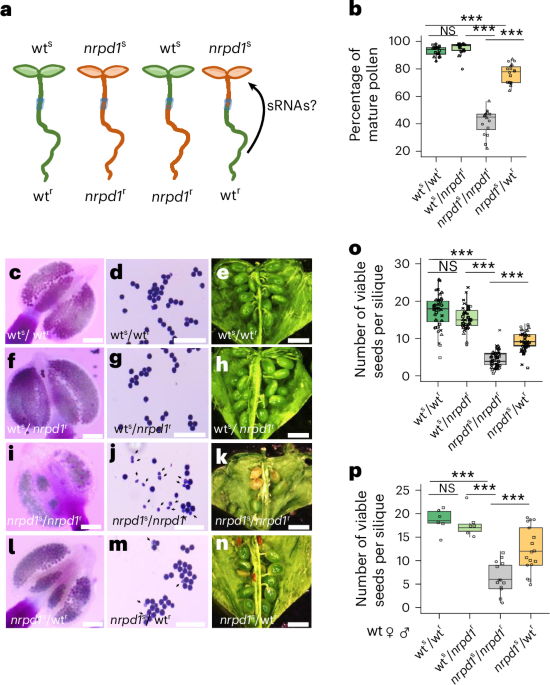

Fig. 1: Grafting nrpd1 scion to wt rootstock restores pollen development and seed set in Capsella rubella.

a, Scheme of the experimental design for hypocotyl grafting. b, Percentage of mature pollen dissected from anthers at stage 12–13 from wts/wtr, wts/nrpd1r, nrpd1s/nrpd1r and nrpd1s/wtr. Three biological replicates derived from independent plants were analysed. Technical replicates in each biological replicate are denoted by triangles, squares and circles. Statistical significance was assessed using a beta-binomial generalized linear model, followed by Tukey-adjusted pairwise comparisons, two-sided. The asterisks mark statistically significant differences (***P < 0.001). The exact P values are provided in the source data. c,d,f,g,i,j,l,m, Alexander staining testing the viability of mature pollen after grafting wts/wtr (c,d), wts/nrpd1r (f,g), nrpd1s/nrpd1r (i,j) and nrpd1s/wtr (l,m). Scale bars, 100 µm. Arrows indicate aborted pollen. The experiment was repeated twice. e,h,k,n, Seed number per silique in wts/wtr (e), wts/nrpd1r (h), nrpd1s/nrpd1r (k) and nrpd1s/wtr (n). Scale bars, 1 mm. o, Seed number per silique of indicated genotypes. Numbers are based on four biological replicates from individual plants per genotype. Nine or ten siliques were analysed for each plant. Siliques from each replicate are denoted by triangles, squares, circles and crosses. The asterisks mark statistically significant differences (***P < 0.05), Kruskal–Wallis test followed by pairwise Mann–Whitney U-tests with Holm–Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. The exact P value is provided in the source data. p, Seed number per silique derived from crossing wt plants with pollen of grafted plants of the indicated genotypes. Seed numbers based on two biological replicates from individual plants per genotype (***P < 0.05), Kruskal–Wallis test followed by pairwise Mann–Whitney U-tests with Holm–Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. The exact P value is provided in the source data. In b, o and p, centre lines show the medians; box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles; and whiskers extend 1.5× the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th percentiles. ♀, female; ♂, male; NS, not significant.

As expected, nrpd1s/nrpd1r grafts exhibited a reduced amount of mature pollen compared with wts/wtr and wts/nrpd1r grafts, consistent with the previously reported pollen defect in the Capsella nrpd1 mutant (Fig. 1b–d,f,g,i,j)22. Strikingly, we observed a significant increase in mature pollen in nrpd1s/wtr compared with control nrpd1s/nrpd1r grafts (Fig. 1b,i,j,l,m), which was reflected by a significantly higher seed set in nrpd1s/wtr grafts (Fig. 1e,h,k,n,o). The seed set was similarly increased when pollinating wt plants with pollen from nrpd1s/wtr grafts (Fig. 1p), revealing that the nrpd1 pollen was viable after grafting. Nevertheless, although seed set was significantly increased upon grafting, it was not completely restored, suggesting that viable nrpd1 pollen is less efficient in fertilization. To test whether reduced fertilization efficiency is a consequence of pollen germination or pollen tube elongation defects, we analysed pollen tube growth of pollen derived from different graft combinations using Aniline blue staining. This analysis did not reveal a major germination or elongation defect of nrpd1 mutant pollen (Supplementary Fig. 1a). However, we found a significantly reduced number of ovules being targeted by pollen tubes when pollinated with nrpd1s/nrpd1r pollen (Supplementary Fig. 1a,b), suggesting that loss of NRPD1 impairs pollen tube guidance. The number of targeted ovules increased when pollinated with nrpd1s/wtr-derived pollen, indicating that grafting can restore functionality of nrpd1 pollen.

Our previous work also revealed a maternal nrpd1 effect on seed number22. To test whether this maternal defect could be suppressed by grafting, we pollinated grafted maternal plants with wt pollen. However, the maternal nrpd1 seed defect was not suppressed by grafting; we observed similar frequencies of abnormal seeds when pollinating nrpd1s/wtr plants with wt pollen (Supplementary Fig. 2). Together, these data indicate that a long-distance mobile signal from the wt rootstock to the nrpd1 scion restores pollen viability and contributes to fertilization efficiency.

Grafting restores siRNAs in pollen, but not in the endosperm

To test whether NRPD1-dependent siRNAs can move from roots to shoots and thereby suppress the nrpd1 pollen defect after grafting, we isolated sRNAs of mature pollen from wts/wtr, nrpd1s/nrpd1r and nrpd1s/wtr grafted genotypes. The sRNA profiles were highly correlated among biological replicates of the same genotype, but were clearly distinct between genotypes (Extended Data Fig. 1a,b). Consistent with previous findings22,23, nrpd1s/nrpd1r pollen was depleted for siRNAs in the 21- to 24-nucleotide size range (Fig. 2a–c and Extended Data Fig. 1c). NRPD1-dependent siRNAs accumulated over both transposable elements (TEs) and genes (Fig. 2b,c). Notably, in line with suppression of the nrpd1 pollen defect after grafting, there was a substantial restoration of global siRNA levels in pollen of nrpd1s/wtr grafted plants, which was particularly prominent over genes and TEs (Fig. 2a–c and Extended Data Fig. 1c).

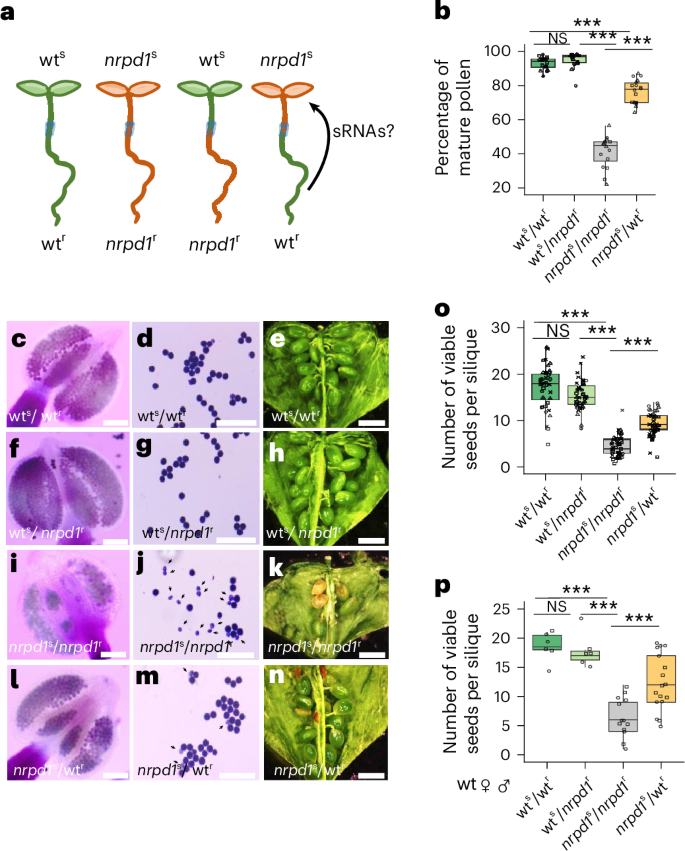

Fig. 2: Grafting of nrpd1 scion to wt rootstock restores abundant PMsiRNAs in pollen.

a, An overview of the alignment of the sRNA reads from 21- to 24-nucleotide-long mapping to chromosome 1. Green, wts/wtr; black, nrpd1s/nrpd1r; orange, nrpd1s/wtr. b,c, Abundance of TE-derived (b) and gene-derived (c) sRNAs in a size range of 21 to 24 nucleotides. d, Venn diagram depicting the overlap of PMsiRNA clusters with NRPD1-dependent siRNA clusters. e, Pie chart depicting the proportion of siRNAs generated from the 169 PMsiRNA clusters relative to the total siRNA abundance from all NRPD1-dependent clusters. f, Pie chart displaying the length distribution of siRNAs generated from the 169 PMsiRNA clusters. g, Percentage of PMsiRNA clusters mapping to defined genomic features: gene body, 2 kb upstream of genes, intergenic region and TEs. h, PMsiRNA accumulation (RPM, reads per million) at specific genomic features. Asterisks indicate statistically significant enrichment calculated by a two-sided Fisher’s exact test (***P < 0.001, *P < 0.05). UTR, untranscribed region.

By comparing siRNAs in pollen of nrpd1s/nrpd1r and nrpd1s/wtr grafts, we identified 178 NRPD1-dependent siRNA clusters that were significantly restored after grafting (DESeq2, P < 0.05, log2(fold change) < −1). Nearly all of these (169) overlapped with the 3,100 NRPD1-dependent siRNA clusters identified by comparing nrpd1s/nrpd1r with wts/wtr pollen (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Table 1). These 169 clusters were defined as PMsiRNAs after grafting in pollen. The nine clusters that were not identified as NRPD1-dependent siRNAs in wts/wtr were below the significance threshold, but were expressed in wt pollen (Extended Data Fig. 1d).

Strikingly, the 169 PMsiRNA clusters accounted for approximately half (52%) of all siRNA reads present in the 3,100 NRPD1-dependent siRNA clusters (Fig. 2e). This finding reveals that in pollen, nearly half of the NRPD1-dependent siRNAs are produced from a few specific loci and are either non-cell autonomous or triggered by non-cell-autonomous signals.

The 169 PMsiRNA clusters contained ~19% of 21-nucleotide siRNAs, ~30% of 22-nucleotide siRNAs, ~30% of 23-nucleotide siRNAs and ~21% of 24-nucleotide siRNAs (Fig. 2f), which was similar to the size distribution present in the 3,100 NRPD1-dependent siRNA clusters (Extended Data Fig. 1e) and consistent with the previously reported dependence of 24-nucleotide and 21- or 22-nucleotide siRNAs on NRPD1 in pollen22,23. The 23-nucleotide siRNAs function as passenger strands during 24-nucleotide siRNA loading into AGO4 and are efficiently sliced by AGO424,25. Their accumulation suggests that they are not loaded into AGO4. Nevertheless, because the function of 23-nucleotide siRNAs is coupled to that of 24-nucleotide siRNAs, 23-nucleotide siRNAs were not considered further in our analyses. The majority of PMsiRNA loci accumulated siRNAs on both sense and antisense strands (Extended Data Fig. 1f,g), suggesting that they were derived from Dicer-mediated cleavage of double-stranded RNAs. PMsiRNA clusters mapped to TEs, intergenic regions, as well as gene body and promoter regions (Fig. 2g,h), suggesting that PMsiRNAs play a regulatory role not only on TEs, but also on genes. More than half of genic loci accumulating PMsiRNAs were predominantly expressed in reproductive tissues, whereas only eight TEs had detectable expression in reproductive tissues (Supplementary Fig. 3).

SiRNAs exert their functions upon binding to Argonaute (AGO) proteins, each characterized by distinct 5′ nucleotide preferences26. The 24-nuceotide PMsiRNAs exhibited a 5′ adenine (A) bias, suggesting they are sorted into AGO4 or closely related AGO proteins (Fig. 3a), whereas 21- and 22-nucleotide PMsiRNAs exhibited enrichment of both 5′ uridine (U) and A, suggesting preferential sorting into AGO1 and AGO2 (Fig. 3a).

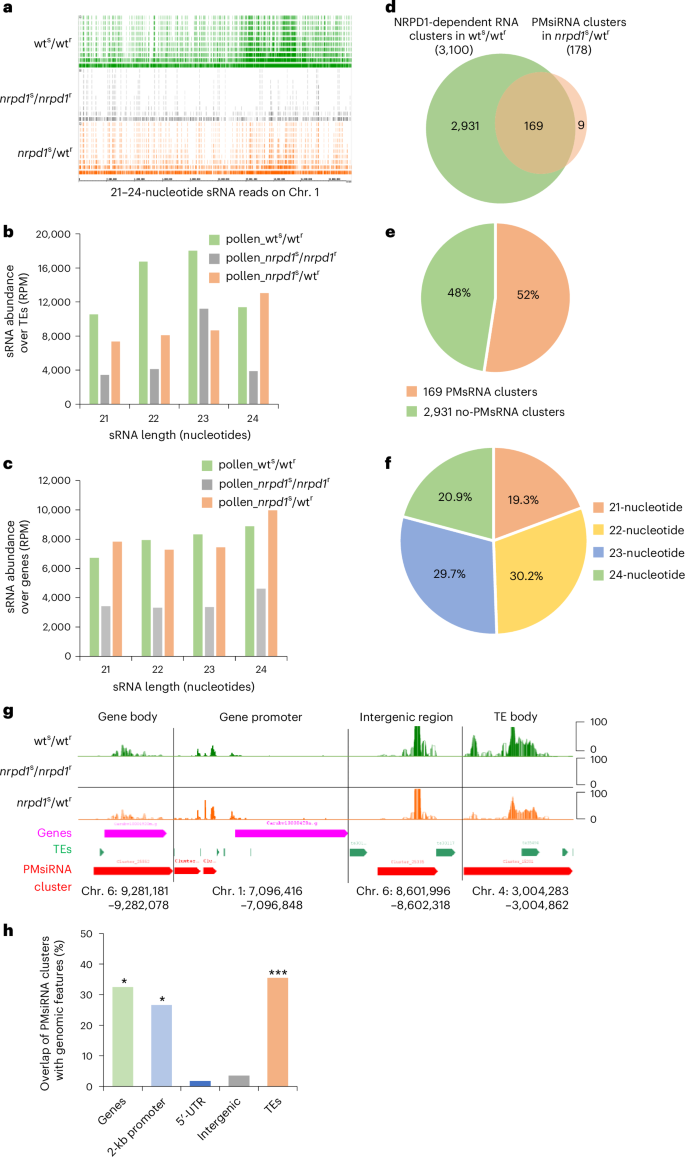

Fig. 3: PMsiRNAs bind to AGO1.

a, Percentage of 21- to 24-nucleotide PMsiRNAs starting with specified 5′ nucleotides. b, sRNA abundance of AGO1-bound sRNAs in wt and nrpd1 buds. The RPM value is shown. c,d, Percentage of AGO1-bound sRNAs with specified 5′ nucleotides from 21- to 24-nucleotide PMsiRNAs in wt (c) and nrpd1 (d). e, In total, 127 siRNA clusters overlap between 169 PMsiRNA clusters and 2,674 AGO1-bound Pol IV-dependent clusters. f. Examples of loci accumulating PMsiRNAs that are bound by AGO1. The RPM value is shown. RIP, RNA immunoprecipitation.

To directly test whether PMsiRNAs load into AGO1, we performed AGO1-RNA immunoprecipitation from wt and nrpd1 flower bud tissues to profile AGO1-bound siRNAs. Consistent with AGO1’s preference for 21-nucleotide siRNAs27, we found 21-nucleotide siRNAs to be enriched in the AGO1-RNA immunoprecipitation samples of both genotypes (Fig. 3b). Also consistent with the preference of AGO1 for sRNA with a 5′ terminal uridine (U)28, AGO1-bound PMsiRNAs were enriched for U (Fig. 3c,d). We identified clusters of AGO1-bound siRNAs in wt and nrpd1 and tested which of these clusters were significantly enriched in wt tissues (DESeq2, P < 0.05, log2(fold change) < −1). Based on this analysis, we identified 2,674 NRPD1-dependent AGO1-bound siRNA clusters, of which 127 were PMsiRNA clusters (Fig. 3e,f). Based on these data, we conclude that PMsiRNAs can be loaded into AGO1, suggesting that they participate in gene silencing through a PTGS mechanism.

Among those genes overlapping with PMsiRNA clusters were many associated with endosperm development, including AGAMOUS-LIKE genes AGL28, AGL35, AGL62 and paternally expressed imprinted genes, including YUC10, as well as genes involved in pectin metabolism (Extended Data Figs. 2 and 3a and Supplementary Table 2)29,30,31. Several of those genes were previously found to generate siRNAs in the endosperm (sirenRNAs)31, suggesting that PMsiRNAs and sirenRNAs are generated from a similar set of loci. We tested this hypothesis by overlapping PMsiRNA loci with our previously identified siren loci31 in the endosperm and found that nearly all PMsiRNA clusters correspond to siren loci (Extended Data Fig. 3b). Given the strong overlap of PMsiRNAs and sirenRNAs, we tested whether we could restore sirenRNA formation in the endosperm by grafting. We sequenced sRNAs from manually dissected endosperm at 6–7 days after pollination from seeds of grafted genotypes wts/wtr, nrpd1s/nrpd1r and nrpd1s/wtr. We identified 1,031 NRPD1-dependent siRNA clusters in the endosperm by comparing wts/wtr with nrpd1s/nrpd1r (Extended Data Fig. 3c,d). Similar to previously published data31, sirenRNA clusters were enriched for 24-nucleotide siRNAs (Extended Data Fig. 3e), differing from the size distribution of PMsiRNAs that accumulated predominantly 21- and 22-nucleotide siRNAs (~50%) and only ~21% of 24-nucleotide siRNAs (Fig. 2f). The vast majority of PMsiRNA clusters (164 of 169) were also detected in wts/wtr endosperm (Extended Data Fig. 3d). In the endosperm, those clusters accumulated substantially higher levels of siRNAs compared with pollen (Extended Data Fig. 3f–h). However, unlike in pollen, siRNAs were not restored in the endosperm upon grafting (Extended Data Fig. 3f–h). These data reveal that PMsiRNAs are present in both pollen and endosperm, but the mobile signal after grafting is only transmitted from roots to male reproductive cells.

PMsiRNAs do not restore DNA methylation after grafting

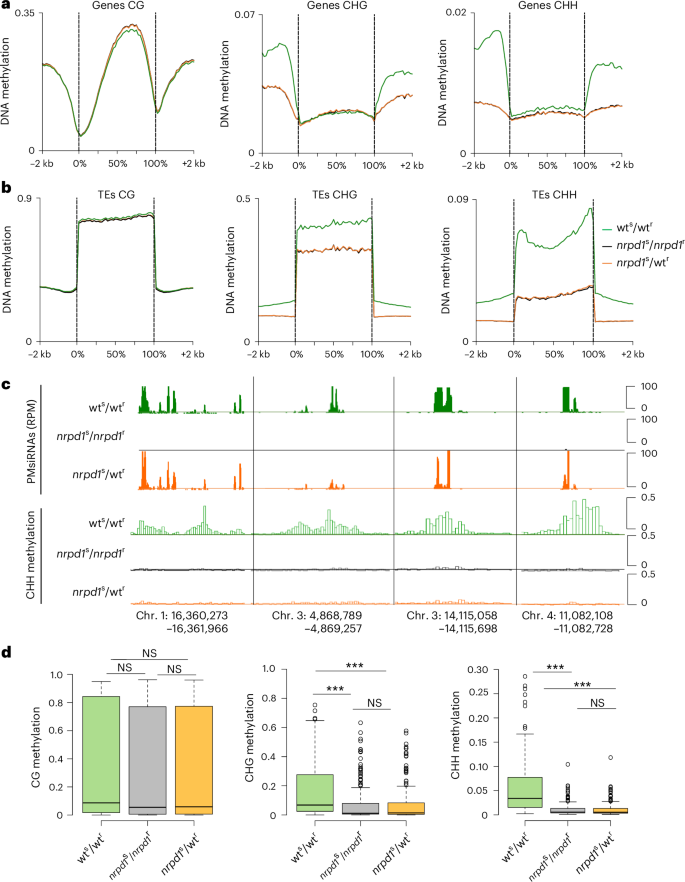

Because NRPD1-dependent siRNAs have a functional role in guiding DNA methylation through the RdDM pathway32, we addressed the question of whether PMsiRNAs induced DNA methylation in nrpd1s/wtr and thereby contribute to restoring pollen viability. We conducted bisulfite sequencing of scion leaves, microspores and mature pollen grains (MPG) from three grafted genotypes: wts/wtr, nrpd1s/nrpd1r and nrpd1s/wtr. We observed a global depletion of CHG and CHH methylation on TEs and genes in nrpd1s/nrpd1r and nrpd1s/wtr microspores, pollen and scion leaves, revealing that grafting did not restore global DNA methylation (Fig. 4a,b and Extended Data Figs. 4a,b and 5a,b). Of 169 PMsiRNA loci, only 25 were methylated in the CHG and CHH context in wts/wtr leaves, microspores and pollen; however, their methylation status remained depleted in nrpd1s/wtr (Fig. 4c,d, Extended Data Figs. 4c and 5c and Supplementary Fig. 4). These data suggest that PMsiRNAs restore pollen viability after grafting by functioning through a pathway distinct from RdDM. It furthermore suggests that the restoration of DNA methylation by graft-transmissible siRNAs requires a functional Pol IV, consistent with previous data8. We also tested whether DNA methylation would be restored in the progeny derived after self-fertilization of grafted nrpd1s/wtr by bisulfite sequencing of leaves from 10-day-old seedlings. However, the DNA methylation profile of the graft-derived progeny was depleted for CHG and CHH methylation, similar to leaves from nrpd1s/nrpd1r (Extended Data Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig. 4), revealing that PMsiRNAs had no transgenerational effects on DNA methylation in the absence of a functional Pol IV.

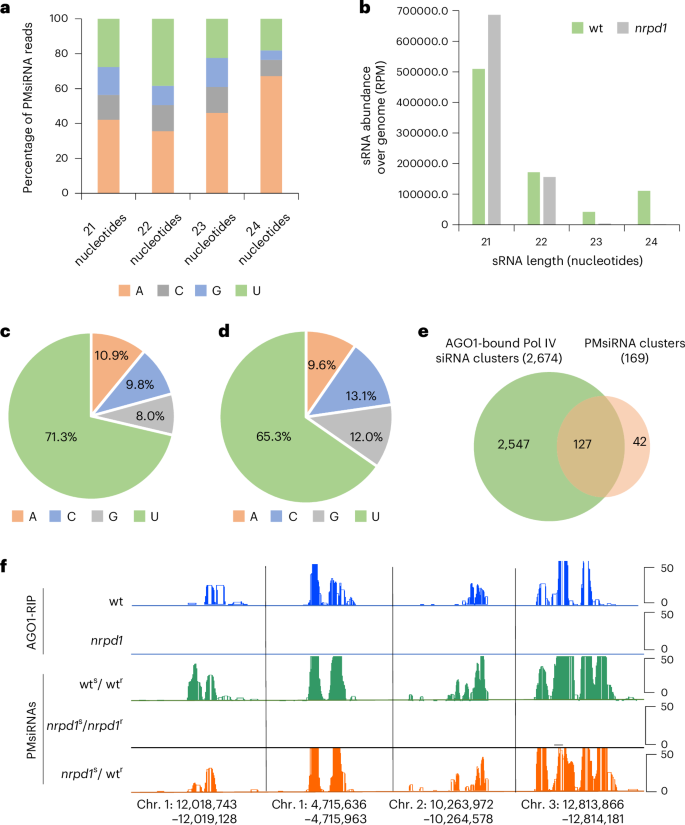

Fig. 4: Grafting does not restore DNA methylation at PMsiRNA loci in microspores.

a,b, Metagene plots showing global DNA methylation levels of genes (a) and TEs (b) at CG, CHG and CHH positions. c, Examples of CHH methylation in microspores at four PMsiRNA loci of indicated genotypes. d, Boxplots showing methylation levels of all PMsiRNA loci (n = 169) of the indicated genotypes. Means of two biological replicates were computed. Centre lines show the medians; box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles; and whiskers extend 1.5× the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th percentiles. The asterisks mark statistically significant differences (***P < 0.001). Statistical significance of differences was determined using the pairwise two-sided Mann–Whitney U-test; exact P values are provided in the source data. kb, kilobase.

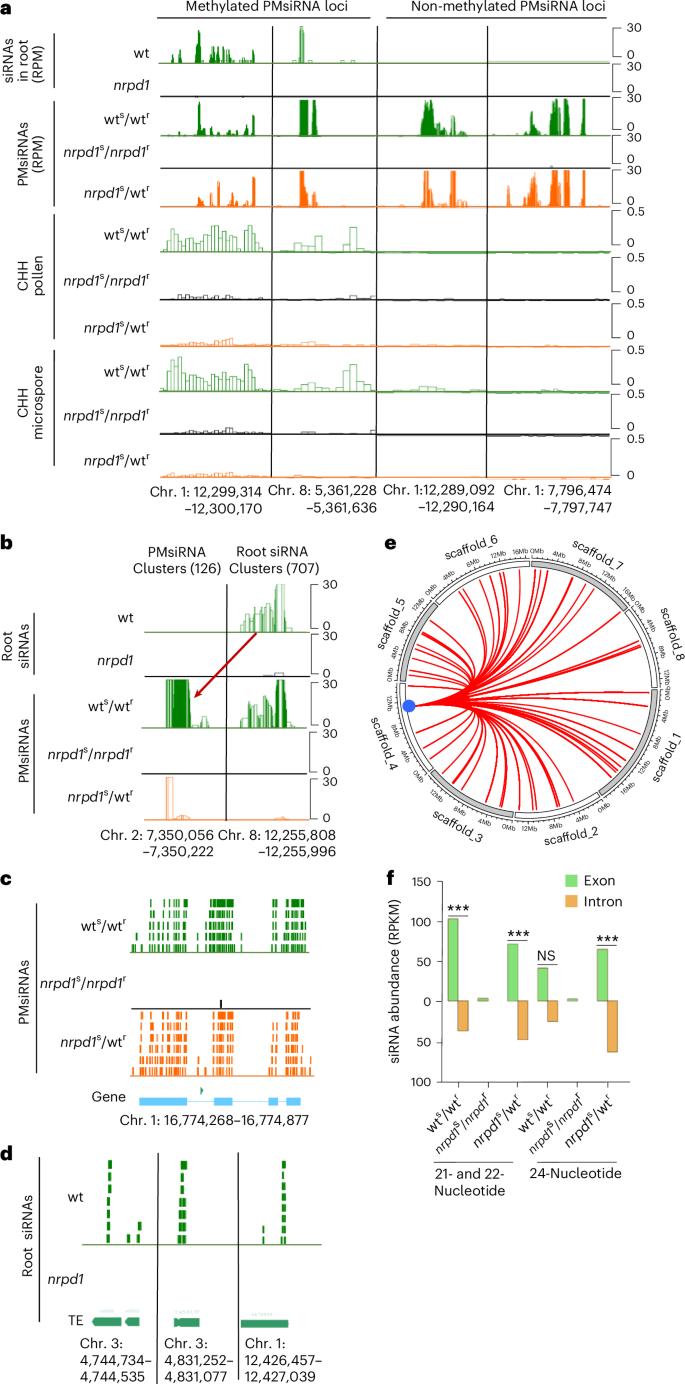

Pol IV-dependent siRNAs from roots trigger amplification of PMsiRNAs

To test whether PMsiRNAs are indeed generated in roots, we isolated and sequenced sRNAs from wt and nrpd1 roots, identifying 9,085 NRPD1-dependent siRNA loci in wt roots, with most of them generating siRNAs of 21 or 22 nucleotides and 24 nucleotides (Extended Data Fig. 7a–c). Only 25 of these loci perfectly overlapped with PMsiRNA loci (Fig. 5a and Extended Data Fig. 7d). However, when allowing for up to three mismatches to their predicted target mRNAs, we identified 707 root loci generating Pol IV-dependent 21- and 22-nucleotide siRNAs that aligned to 126 of 169 PMsiRNA loci (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). In contrast to PMsiRNAs that accumulated over longer genomic regions, root-derived siRNAs were preferentially derived from TEs and accumulated as highly abundant siRNAs over very narrow regions (Fig. 5c,d and Extended Data Fig. 7e,f). The vast majority (84%) were generated from both strands, ruling out that these loci are new miRNAs. Root loci significantly overlapped with helitrons and Harbinger DNA elements (Extended Data Fig. 7g) and were enriched for specific sequence motifs (Extended Data Fig. 7h), suggesting specific binding of transcription factors to those motifs.

Fig. 5: siRNAs generated from root loci induce amplification of secondary siRNAs.

a, Examples of CHH methylation and siRNA abundance in roots and microspores. The first two loci are examples of methylated PMsiRNA loci that accumulate siRNAs in roots. The third and fourth loci are unmethylated PMsiRNA loci without siRNA accumulation in roots. b, An example showing siRNAs in roots targeting pollen PMsiRNA loci. The red arrow indicates siRNAs from the original root locus that can be mapped to the PMsiRNA locus with up to three mismatches. c, Example of PMsiRNAs in pollen mapping specifically to exons of a coding gene. d, Examples of root siRNAs accumulating in narrow regions of TEs. e, Circos figure showing an example of root siRNAs from multiple root loci targeting a single PMsiRNA locus in trans. Root siRNAs from 55 loci can trans target a single PMsiRNA cluster indicated by a blue circle (Cluster_17934: Chr. 4, 11082108–11082728). Scaffold indicates chromosome. f, The abundance of 21- and 22-nucleotide and 24-nucleotide PMsiRNA over exons and introns of coding genes. Asterisks indicate statistically significant enrichment calculated by a two-sided Fisher’s exact test (***P < 0.001). RPKM, reads per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads.

Interestingly, we found that siRNAs from many distinct root loci could target one specific PMsiRNA cluster (Fig. 5e and Supplementary Table 4). Thus, 35 of the 126 PMsiRNA loci were targeted by siRNAs from at least five different root loci. For example, PMsiRNA cluster_2988 (Chr. 1: 12299314–12300170) is trans targeted by siRNAs from 121 root loci, cluster_17934 (Chr. 2: 11082108–11082728) by siRNAs from 55 root loci, cluster_4816 by siRNAs from 27 root loci, and cluster_33527 by siRNAs from 24 root loci. Interestingly, many of the PMsiRNA loci that are targeted by multiple root loci overlap with helitrons: PMsiRNA cluster_2988 contains three helitrons, cluster_17934 overlaps with one helitron, cluster_4816 intersects with gene Carubv10011462m.g, encoding a pectin methylesterase inhibitor that contains a helitron in the intron region, and cluster_33527 intersects with gene Carubv10026508m.g, encoding a member of the ARF GAP domain family and also contains a helitron in the intron region. These data align with the enrichment of root siRNA loci for helitrons (Extended Data Fig. 7g), indicating that helitron-derived root siRNAs target conserved regions in trans.

We speculated that NRPD1-dependent siRNAs produced in roots may target PMsiRNA loci in trans and induce secondary siRNA amplification, as previously proposed33. Consistent with this idea, we found that there was a preference for PMsiRNAs to be generated from exonic regions of genes (Fig. 5f), with several (21) PMsiRNA loci exclusively accumulating over exons (Fig. 5c). We quantified the accumulation of PMsiRNAs over exons and introns and found a comparable exonic bias for 24-nucleotide and 21- or 22-nucleotide siRNAs in pollen of the nrpd1s/wtr grafts (Fig. 5f). Target cleavage by miRNA-loaded AGO1 can trigger the biogenesis of secondary siRNAs that have a distinctive phased configuration34. However, we did not detect elevated phasing scores at PMsiRNA-generating clusters, suggesting that the trigger for secondary siRNA formation is not one distinct cleavage event, but possibly multiple cleavage events causing out-of-phase secondary siRNA formation.

We addressed the question of whether PMsiRNA formation is indeed specifically triggered from root-derived siRNAs or whether the trigger is also present in other sporophytic organs. Indeed, the majority of siRNAs of the 707 root clusters were also present in non-grafted wt leaves (Extended Data Fig. 7i), suggesting that the trigger siRNAs for PMsiRNA formation are not root specific but are generated in different sporophytic organs. Consistently, pollen of wts/nrpd1r grafts developed normally and accumulated PMsiRNAs (Fig. 1f–h and Supplementary Fig. 5). We thus conclude that the trigger for PMsiRNA formation can also be generated in other sporophytic tissues than roots.

Secondary siRNA formation requires the activity of RDR6, which processes cleaved messenger RNA substrates into double-stranded RNA molecules that serve as substrates for DCL2 and DCL4 to produce 22-nucleotide and 21-nucleotide siRNAs, respectively7. To further investigate whether the amplification of PMsiRNAs relies on a conventional PTGS mechanism, we used CRISPR–Cas9 to generate two loss-of-function mutant alleles of the single RDR6 orthologue in Capsella (Supplementary Fig. 6a,b). These alleles featured deletions after amino acids 432 and 434, resulting in truncated proteins that lacked the conserved catalytic Asp867 residue (Supplementary Fig. 6b)35. Both mutant alleles exhibited severely reduced pollen numbers, attributable to impaired anther locule formation and disrupted pollen gametogenesis (Extended Data Fig. 8). Frequently, only one or two of the four anther locules developed, and pollen in these locules was partially inviable (Extended Data Fig. 8m–x). Inviable pollen arrested at various developmental stages, with a predominant arrest at the microspore stage (Extended Data Fig. 8m–r), mirroring the defects observed in Capsella nrpd1 mutants (Extended Data Fig. 8g–j)22. However, unlike nrpd1, which does not have notable tapetal defects (Extended Data Fig. 8g–j)22, rdr6 mutants exhibited a significant delay in tapetal degeneration (Extended Data Fig. 8m–r). In rdr6 mutants, we frequently observed anther locules filled with tapetum-like structures (Extended Data Fig. 8s–x) or undegraded tapetum with no or few pollen grains inside (Extended Data Fig. 8s–x).

Because of the severe defects in pollen formation in rdr6, we focused on isolating and sequencing sRNAs from mature anthers of wt and rdr6 plants rather than from pollen (Extended Data Fig. 9a–c). In wt anthers, siRNA accumulation was detected at 154 of 169 PMsiRNA loci. Surprisingly, PMsiRNA accumulation was also observed in rdr6 anthers of both mutant alleles, with the level of accumulation being substantially higher in rdr6 compared with wt anthers (Extended Data Fig. 9d,e). The general trend was similar between both alleles, with some variation due to variable numbers of developed locules. The increased accumulation of PMsiRNAs in rdr6 anthers is possibly a consequence of the impaired tapetal degradation in rdr6 (Extended Data Fig. 8m–r), suggesting that PMsiRNA generation occurs in the tapetum. By contrast, the formation of RDR6-dependent TAS3 siRNAs1 was strongly impaired in rdr6 mutants (Extended Data Fig. 9f), confirming that Capsella RDR6 functions as a canonical orthologue of RDR6. We thus speculate that other RDRs are involved in this process and possibly act redundantly with RDR6 in PMsiRNA formation32.

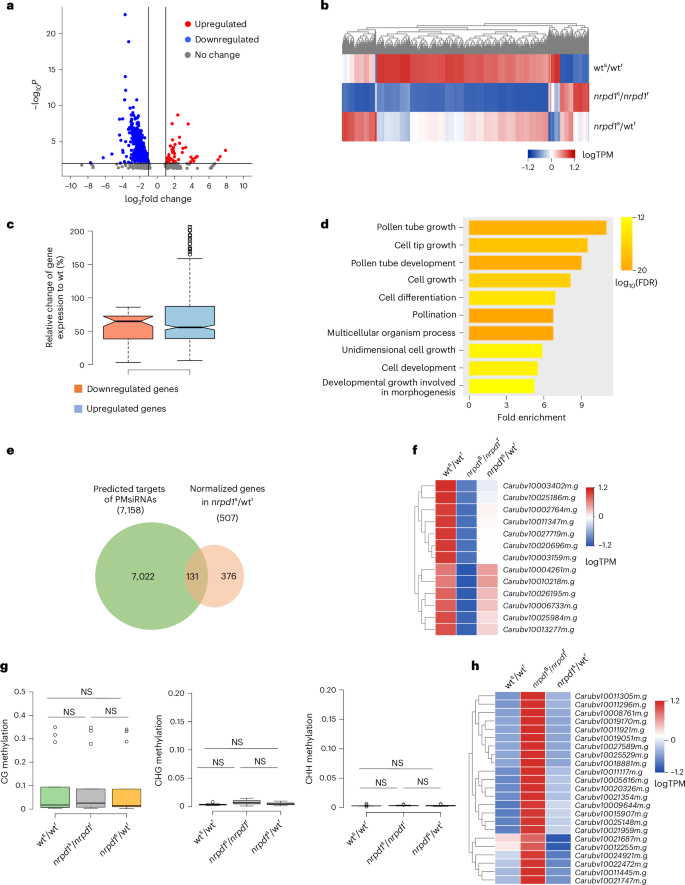

Grafting partially restores gene expression in microspores

To dissect the functional role of PMsiRNAs in regulating pollen development, we conducted RNA sequencing of microspores of wts/wtr, nrpd1s/nrpd1r and nrpd1s/wtr genotypes. Transcriptome analysis of microspores identified 751 differentially expressed genes in nrpd1s/nrpd1r compared with wts/wtr; of these, 629 genes were downregulated and 122 genes upregulated (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Table 5). The expression of the majority of deregulated genes (454 downregulated genes and 53 upregulated genes) was partially restored in nrpd1s/wtr (Fig. 6b,c and Supplementary Table 5). Transcripts for NRPD1 were not among the restored genes, ruling out that long-distance movement of NRPD1 mRNAs is responsible for the normalization of pollen development. Restored genes had functional roles related to pollen development and pollen tube growth (Fig. 6d) and 131 overlapped with predicted targets of 21- or 22-nucleotide PMsiRNAs (Fig. 6e and Supplementary Table 6). The majority of PMsiRNAs were directed against genes that were downregulated in nrpd1, although 13 targeted upregulated genes (Fig. 6f). The restored expression of those 13 targets was not connected to changes in DNA methylation (Fig. 6g) or to the accumulation of siRNAs, suggesting that PMsiRNAs directly or indirectly contribute to male gametophyte development by mechanisms that are probably independent of RdDM and the slicing of mRNA targets.

Fig. 6: Grafting normalizes gene expression in microspores.

a, Volcano plot showing differentially expressed genes in nrpd1/nrpd1 compared with wt/wt. Blue, downregulated genes; red, upregulated genes. b, Heatmap showing genes with recovered expression after grafting in nrpd1s/wtr microspores. c, Graph showing the relative change of upregulated (n = 53 ) and downregulated (n = 454) genes in comparison with wt after grafting. Means of two biological replicates were computed. Centre lines show the medians; box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles; and whiskers extend 1.5× the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th percentiles. d, Enriched Gene Ontology terms of biological processes of normalized genes after grafting in nrpd1s/wtr microspores. The top ten Gene Ontology terms are shown. e, Overlap of normalized genes in nrpd1s/wtr microspores and predicted targets of PMsiRNAs. f, Heatmap showing expression of potentially PMsiRNA targeted genes that are deregulated in nrpd1 and normalized after grafting. The log(transcripts per million (TPM)) value is shown. g, Methylation levels of normalized PMsiRNA target genes (n = 13) shown in f. Means of two biological replicates were computed. Centre lines show the medians; box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles; whiskers extend 1.5× the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th percentiles. P > 0.05. Statistical significance of differences was determined using the pairwise two-sided Mann–Whitney U-test; exact P values are provided in the source data. h, Heatmap showing grafting normalized expression of genes that accumulate PMsiRNAs at the gene body or 2 kb promoter regions. FDR, false discovery rate.

We also considered that the regulation of transcript abundance from PMsiRNA-generating loci themselves might be critical for pollen viability. To investigate this, we examined transcript accumulation at PMsiRNA loci across wts/wtr, nrpd1s/nrpd1r and nrpd1s/wtr genotypes. Our analysis revealed that most loci exhibited transcript hyperaccumulation in nrpd1s/nrpd1r microspores, with approximately half showing reduced transcript levels following grafting (Fig. 6h and Extended Data Fig. 10). We speculate that the ectopic accumulation of transcripts from PMsiRNA loci in nrpd1 pollen may underlie the observed pollen arrest phenotype. We propose that a key function of sporophytically derived siRNAs is to suppress RNA accumulation from PMsiRNA loci, thereby supporting proper pollen development.