San Diego Unified has officially taken the big housing leap. In fact, officials have taken the biggest housing leap ever attempted by a K-12 school district – by far.

During Monday and Tuesday night’s board meetings, district trustees approved four joint-occupancy housing proposals that could bring thousands of affordable housing units reserved for their workforce to district owned land.

With the addition of a proposal approved in December, the district has advanced proposals to build a total number of 2,500 units. That’s nearly triple the number of such units built throughout California. The district’s potential housing portfolio jumps to more than 2,800 units when you add the district’s sole existing complex and another planned project.

What stands out in San Diego Unified’s recent housing decisions is that district officials didn’t just go big, they uniformly went as big as they possibly could. Experts say the district’s unprecedented moves could be the tipping point of a years-long, but slow growing, movement to build housing on K-12 district owned land in California.

But even as officials watch the efforts with elation, there are a slew of unknowns to be figured out.

“San Diego Unified is positioning itself as the undisputed leader in workforce housing in the state, and actually in the country,” said Greg Francis, the education workforce housing project lead at the California School Boards Association. “The district is setting a new bar and other districts should be inspired by what they’re doing.”

The Slow Start and the Tipping Point

Affordable education workforce housing gained considerable momentum with the release of a 2022 report that found that California districts had at least 75,000 acres of developable land. State Superintendent Tony Thurmond has been a cheerleader of the approach, advocating for districts to build 2.3 million units of housing. That sum could nearly wipe out California’s housing shortage.

That’s why lawmakers have also sought to grease districts’ housing wheels in recent years, passing multiple laws that do things like remove rezoning requirements for housing on district land and exempts such projects from environmental reviews.

For proponents of affordable education workforce housing, the strategy is a sort of twofer. If built at scale, they could help ease the housing crisis that’s gripped California. The units may also decrease costs for often financially burdened school staff, helping districts recruit and retain employees.

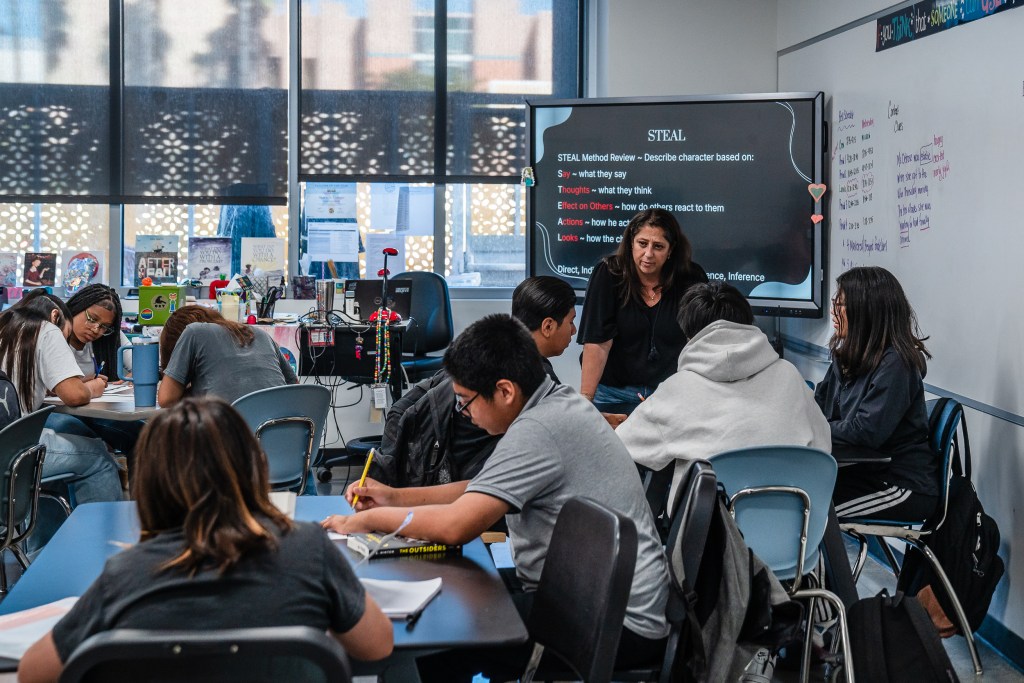

A teacher speaks to eighth-grade students at Logan Memorial Educational Campus in Logan Heights on Nov. 7, 2025. Ariana Drehsler for Voice of San Diego

A teacher speaks to eighth-grade students at Logan Memorial Educational Campus in Logan Heights on Nov. 7, 2025. Ariana Drehsler for Voice of San Diego

In areas with eye popping housing costs, like San Diego, the impact may be especially impactful, said Kyle Weinberg, the president of San Diego Unified’s teachers union. Those costs exacerbate districts’ struggles to fill hard to staff positions like special education teachers, and also chase away families with young children, fueling the the region’s enrollment decline crisis.

“Educators are feeling the brunt of the regional housing crisis,” Weinberg said. “That’s why we have declining enrollment in schools that then lead to layoffs and transfers that destabilize our school communities. That’s why we made affordable housing a priority for our union.”

Still, despite the enthusiasm, a paltry number of units have been built thus far. That’s frustrated some researchers, like Dana Cuff founder of cityLAB, a center in UCLA’s architecture and urban design department that helped author the 2022 report that identified district housing as such an opportunity.

“The process … is much slower than we might have originally imagined, which is really shocking, given all of our research shows these developments are an unqualified success for districts,” Cuff said.

Cuff points to reports that show that existing workforce housing routinely fills up and often accrues waiting lists. San Diego Unified officials, for example, say they received 2,000 applications for the 54 units that went up for rent at its sole existing complex.

That opportunity is why she thinks San Diego Unified’s moves could be such a gamechanger.

“I think once San Diego is successful at this, other districts are going to follow suit,” Cuff said.

A More Expansive Affordability

The district’s recent leap into housing has been years in the making. But the scale is entirely new.

That’s because during their decisions, the board embraced a simple mantra: more. Instead of weighing projects based on how affordable the units they proposed were, at every site trustees chose the proposal that would produce the highest number of units.

That produced even more units than officials had set their sights on. Initially, the board aimed to create housing for 10 percent of its district staff – about 1,500 units. The nearly 2,500 they greenlit would fit closer to 17 percent of its staff.

Board trustees and district officials during a San Diego Unified School Board meeting on Monday, Jan. 26, 2026. The board listens to presentations for proposed housing developments. / Vito Di Stefano for Voice of San Diego

Board trustees and district officials during a San Diego Unified School Board meeting on Monday, Jan. 26, 2026. The board listens to presentations for proposed housing developments. / Vito Di Stefano for Voice of San Diego

In prioritizing quantity, the board disregarded all of the recommendations made by a district committee that reviewed the proposals, which seemed to place a priority on price of units rather than number.

While the district’s YIMBY-maxing inspired some protest from local residents, there seemed to be just as much enthusiasm for it. When the district first began pondering big housing moves nearly a decade ago, that balance was drastically different, Board President Richard Barrera said. He thinks it’s a sign of the times.

“I think that reflects the degree to which housing affordability has just become the issue. Not only for a school district, but for people in this city,” Barrera said.

Even given the more expensive units, all of them met the district’s bar for affordable housing. That more expansive definition stipulated that an affordable unit is one that costs no more than 30 percent of an employee’s pay.

So, even units that would cost 30 percent of the pay of employees who made well over the area median income – of which there are hundreds across the projects – were considered affordable. That eschews the standard method by which federal and state agencies determine affordable housing, which ties rent prices to a region’s area median income.

The district’s method was useful because not all of its employees are eligible to live in traditional affordable housing. Other districts that have faced this paradox, like Los Angeles Unified, have found that their teachers made too much to qualify for the affordable units they built for them.

“The push got us to more of that middle income teacher housing and family housing,” Barrera said. “We were able to get more and provide more affordability to a group of employees that are typically excluded from affordable housing.”

While a significant step, though, the votes don’t seal the deal. They essentially just authorized district staff to begin final negotiations and due diligence on each of the proposals. And the board already had a number of directives for negotiations, from trying to bring down rents to adding additional parking.

‘San Diego Is the First District to Really Go Deep on This’

Exactly how this process will continue to unfold, and how it will work long-term, is still something of an open question. Construction projects face infinite hiccups and renderings never quite come true. Barrera said he’s paying closest attention to whether developers can actually secure the financing they said they could.

The unknowns are also amplified because San Diego Unified’s approach to building affordable education workforce housing is extremely unique.

Instead of building housing with district money, they opened up the process to developers to pitch joint-occupancy projects. That gave them less control over proposals but also meant they wouldn’t have to foot the bill for planning or construction and could make some dough from leasing the land to chosen developers.

People walk to the San Diego Unified School District office in University Heights on Monday, Jan. 26th, 2026. / Vito Di Stefano for Voice of San Diego

People walk to the San Diego Unified School District office in University Heights on Monday, Jan. 26th, 2026. / Vito Di Stefano for Voice of San Diego

The projects they advanced could bring billions in revenue into the district over the proposed 99-year lease terms. Board members, however, made clear they’d prefer to rake in less dough if developers could bring rents down.

The joint-occupancy model also required developers to create district uses at each of the sites. At the largest of the five sites, a proposed 1,500-unit development on the district’s former headquarters in University Heights, developers pitched a public pool, sports courts, parks, retail and a teacher training facility. At multiple other sites, developers plan to build childcare centers for district staff.

“San Diego is the first district to really go deep on this,” said Francis, the CSBA project lead. “A lot of people just don’t know about this option yet. Our role, we feel, at CSBA is to really spotlight this and get the word out.”

The organization is so bullish about the strategy’s potential that they’ve scheduled a workshop at the Livia complex, an existing development on San Diego Unified-owned land in Scripps Ranch. The site is the only existing joint occupancy educator workforce housing project in California. In addition to 53 units for district employees, it features more than 200 market rate units and a newly opened STEAM for district students.

There are also still a whole slew of questions to be answered about how the complexes will work day to day. What happens when a district educator takes a job elsewhere? How will applicants for units be prioritized should there be a waitlist?

Officials approved a resolution last January that lays out recommendations for how the projects should operate. They include everything from discouraging application fees to union-friendly policies to setting timelines for continued eligibility should a resident be laid off (39 months) or leave voluntarily (12 months, or end of lease, whichever is greater.)

Those recommendations, however, are just that – recommendations.

Trustee Cody Petterson said that finalizing details like this will be a key part of the district’s work in the coming months. The goal is also to iron out any kinks in the process, so it can be shared with officials excited about the strategy’s potential. Petterson said he’s already heard from a slew of local officials eyeing the possibility.

“We’ve used zero taxpayer dollars, we’ve lost no land and we’re going to get thousands of units of housing,” Petterson said. “If we can improve and tighten up our process so it can be generalized across the 1,000 districts in California, it has the possibility to establish a whole new paradigm.”

A New Housing Authority in Town

These five projects, however large, aren’t the end of the district’s housing plans. Barrera said they’re eyeing four more potential sites for which requests for proposals could be issued as early as this year. There’s also the $206 million in Measure U bond funds the district set aside to build housing, none of which was touched.

Looking forward, San Diego Unified Superintendent Fabiola Bagula has her heart set on creating more permanent housing opportunities for district employees.

Fabiloa Bagula, superintendent for the San Diego Unified School District, during a community meeting at Bethune K-8 School on Sept. 24, 2025 at Bay Terraces. / Ariana Drehsler for Voice of San Diego

Fabiloa Bagula, superintendent for the San Diego Unified School District, during a community meeting at Bethune K-8 School on Sept. 24, 2025 at Bay Terraces. / Ariana Drehsler for Voice of San Diego

“I’m really proud of what we accomplished, but I’m also going to pursue this notion around how might we offer this housing to new teachers to recruit them and then potentially actually help them become homeowners?”

But another move from the district could prove to be even more impactful.

Early last year, officials at San Diego Unified and the San Diego Community College District launched announced the formation of a joint Regional Housing Finance Authority. The authority is the third such entity in California, and the first comprised of educational agencies. The agency would be able to generate funds and finance projects via bonds and tax measures.

Bagula said that while the district’s workforce housing efforts were more inward looking, what she hopes to accomplish with the financing authority would have a broader regional impact. This isn’t just about staff, but about strengthening communities.

“I see that as a long term strategy to promote walkable neighborhoods for families,” Bagula said. “I see schools being closed all across the nation, and I’m thinking, how do we think differently? Instead of shutting down a school and having an abandoned building, why don’t we actually build affordable housing and bring families back?”

San Diego Community College District Chancellor Greg Smith echoed that sentiment. His goal is to build a substantial number of units that everyone can afford, he’s open to adding additional agencies to the authority, should their service areas and vision comport with the school districts’.

But it’s the kind of units he wants to build that are most notable. He’s like the agency to focus on high density housing with proximity to employment centers and transit. He hopes they can develop some solid initial plan and put a bond or tax measure on the ballot as soon as 2028 to fund it.

Like many budding urbanists, what’s fueling his ambition is a recent trip to Vienna, the western world’s public housing Mecca. For over a hundred years, the city has continued to evolve its approach, purchasing existing apartments by the thousand and even building sprawling 5,000 unit developments. About half of residents now live in hundreds of thousands of city-owned or rent subsidized apartments.

“That really became my north star. If we can work ourselves up to the point where we can do something at that scale, that would be my goal,” Smith said.