Jazmine Locke has filled out the paperwork and checked all the boxes. As a middle-income worker, she qualifies for California-subsidized day care for her 7-month-old daughter. Yet she holds little hope she will ever make it off the waitlist. Her older son, now 12, never did.

“In my mind, I plan to pay for child care until she doesn’t need it anymore,” said Locke, who lives in Antelope Valley. “That’s not until high school, pretty much.”

Locke, like thousands of other families and providers, is confronting the effects of stalled progress to expand in California’s child-care industry after Gov. Gavin Newsom’s proposed budget — with an estimated $3-billion deficit — did not fund his promised expansion of subsidized child care for the second straight year.

The proposal is a blow for low- and middle-income working parents who were hoping that affordable child care would be in their future. But the demand is so high among eligible families that they remain on waitlists for years, and many children age out before they secure a spot. Leaders in the child-care industry are disappointed that Newsom, who has championed early childhood education, has not fulfilled his pledge.

“We are in a difficult budget situation right now, both within California, as well as so much uncertainty federally right now,” said Nina Buthee, executive director of EveryChild California. “But realizing that this is our child-care governor, there was a lot that was promised to the early care and education field, which I feel is half-done.”

Engage with our community-funded journalism as we delve into child care, transitional kindergarten, health and other issues affecting children from birth through age 5.

The median cost for full-time care for an infant in Los Angeles County is $1,209 a month at a family child-care home and $1,818 a month at a center in 2024, according to data from the California Budget & Policy Center. For a preschooler, it costs $1,121 at a home and $1,271 at a center. And for school-age children, care costs $884 at a home and $959 at a center.

“Thousands of families are on these waiting lists trying to get access to affordable child care,” said Laura Pryor, research director at the California Budget & Policy Center. “With the state not fulfilling its promise for the additional subsidized spaces and walking back that commitment, those families are just going to continue to languish on these waiting lists, and we’re not going to continue with the progress that we’ve seen in previous years.”

In 2021, Newsom pledged to open 206,800 additional subsidized child-care spaces. Roughly 129,000 have been funded. A 2024 trailer bill had promised to open an additional 44,000 child-care slots in the 2026-27 fiscal year, but funding for those slots was omitted in the current budget proposal, and no language was included indicating funding was deferred to a future year.

Under the proposed budget, Newsom has allocated $7.5 billion to child care and development to fund several subsidized care programs and provider pay, training and benefits. At approximately 2% of the total state budget, the proposed funding is similar proportionally to the previous five years.

Overwhelming need

But the need is overwhelming and demonstrates the unabated struggles low-income and middle-class working parents face in their quest for affordable child-care slots.

California is home to 2.1 million children whose families qualify for child-care subsidies based on income and need. The state funds enough slots to subsidize 16% of those who are eligible, according to 2024 estimates. If the 44,000 additional slots pledged for this fiscal year were funded, the supply would expand by 2%. In Los Angeles County as of 2024, 18% of children eligible were enrolled in subsidized care.

“Basically the clock has stopped,” said Donna Sneeringer, president of the Child Care Resource Center, a nonprofit that helps connect families in Southern California with child care and subsidies. CCRC hasn’t enrolled children since March 2025. The resource and referral agency has a waitlist of 25,000 children in their region alone. But with no new spaces and little turnover, the center doesn’t expect much movement. Children remain eligible for financial assistance until they reach age 13.

“They’re really at a standstill until there are new dollars available,” she said.

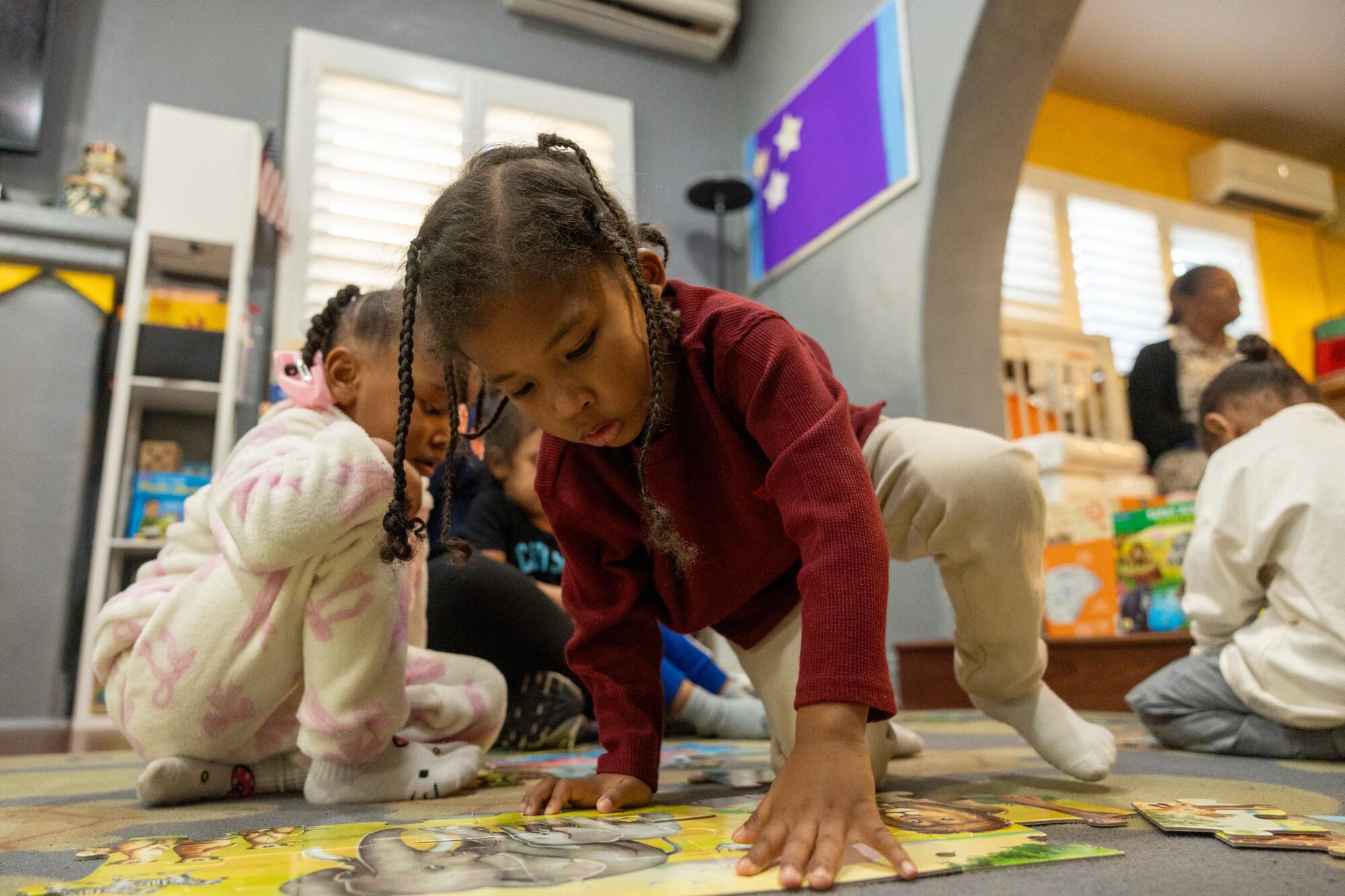

Brix Armstrong works on a puzzle at Aurora Reyes’ family child-care home on Jan. 26.

(Ronaldo Bolanos/Los Angeles Times)

Currently, 366,700 children are enrolled in subsidized child care, up from 210,000 in 2020, thanks to Newsom’s 2021 budget, which came as California navigated an unprecedented surplus and $5 billion in one-time federal pandemic aid meant for child care.

In ongoing budget negotiations, the California Legislative Women’s Caucus is pushing for the state to make good on its promises to open more slots and increase provider pay.

“California families and child-care providers are waiting on promises that haven’t been kept yet,” Assembly Majority Leader Cecilia Aguiar-Curry (D-Winters), chair of the Legislative Women’s Caucus, said in a statement. “For many, many years, we were told there would be 200,000 new child-care slots and fairer provider rates that cover the true cost of care — and that work is far from done.”

Newsom’s office did not comment on the issue and referred questions to the California departments of Health and Human Services and Social Services.

“California has made many recent, unprecedented investments to support California’s child care and early learning system,” the Department of Social Services, which oversees child care, said in a statement.

Frustrations mount

Aurora Reyes runs a family child-care home in Leimert Park and tries to help parents seeking affordable child care.

She is working on helping five families find financial assistance — including three on waitlists for state aid who are enrolled at her own child-care home through Early Head Start. While helpful, the Head Start support is limited and does not cover the number of hours of care the families need. Parents must scramble for alternative care for the remainder of the time, she said.

“They’ve been told that the waiting list could be about three years,” she said. “By the time families are able to get the services, the kids will be in elementary school. And if it’s a family that has school-aged children, by the time they’re able to get services, the kids will be too old.”

Provider Aurora Reyes carries Alijah Hithe as she picks out a book to read at her family child-care home in Leimert Park on Jan. 26.

(Ronaldo Bolanos/Los Angeles Times)

Strain on child-care providers

That lack of financial support for families has a ripple effect on providers. It makes it harder to enroll children, Reyes said.

“If parents don’t go to work because they can’t afford child care, then that pushes child-care providers out of the field,” Reyes said. “Everybody realized that child-care providers were the backbone of California … And now that the pandemic is over, it’s like, ‘OK, you guys have kind of forgotten about us again.’ ”

Stephanie Quintanilla of Koreatown has been on the waitlist to enroll her newborn in subsidized care since she was pregnant. Her oldest daughter is in transitional kindergarten and out of day care, meaning that Quintanilla had to start from scratch on the waitlist.

“There’s a long waitlist ahead of me,” said Quintanilla, who works as an early childhood and education specialist in Cheviot Hills and knows the issue firsthand. “I’m not sure how long it would take for me to get child care.”

She has no idea what she’ll do if she is not off the waitlist by the time she needs to return to work likely in April.

Calculating the cost of child care

Parents whose income is equal to or below 85% of the state median income — currently $9,020 a month for a family of four — and can demonstrate they need child care qualify for California subsidized care. Need is defined by work, schooling, or time required to search for a job or home.

Families are largely ranked for waitlist placement based on what medical, legal and social service programs they qualify for and how much they earn, with those who earn the least securing higher spots on the waitlist.

Those whose income is below 75% — currently $7,959 a month for a family of four — essentially get free care. Those who earn between 75% and 85% must pay a fee capped at 1% of their income, up to $68.60 a month per child for full-time care — the state subsidizes the rest.

In 2023, Quintanilla had to wait about a year before a spot opened up for her oldest daughter. Her time on the waitlist was easier then because she was working from home. This time, her need is more urgent because she’s back in the office and the wait could potentially be longer now that her family’s gross income is higher.

Locke is facing similar worries. To stay afloat, she has had to make sure her family keeps child care front and center.

“I have to make arrangements to make sure that my day care is a priority so that I can be able to go to work,” Locke said. “If that means that I have to sacrifice in other areas, I try to. Even sometimes my day care payments are late.”

Locke pays $1,200 a month for all-day infant care and after-school care at a child-care center for her two children. She feels fortunate because her provider offered her a significant discount that makes the cost more manageable while she is on the waitlist.

Still, it’s her biggest bill after rent.

Promises unfulfilled

Newsom has championed expansion of early childhood education and support for the child-care industry. Under his leadership California fully inaugurated a new grade this academic year, offering free transitional kindergarten to all 4-year-olds at a cost of $2.7 billion. He approved legislation creating Child Care Providers United, which unionized child-care workers across the state, increasing provider pay and establishing healthcare and retirement funds. Family contributions for subsidized care were capped at 1% of a family’s income rather than nearly 10%.

Yet many child-care providers and advocates are disappointed the proposed budget did not include startup funding for a union-backed initiative to overhaul how child-care providers are paid. The long sought change would allow subsidies to better reflect the actual cost of running a day-care home or center.

Current state subsidies in the Los Angeles region are based on the 2018 market rate for care: up to $1,122 for full-time infant care, $1,006 for toddler care and $753 for school-age care at family child-care homes. The rate is below median costs and isn’t an accurate reflection of what they spend to operate today.

Kataleya Lasane, right, listens to child care provider Aurora Reyes speak as Aaron Francis, left, holds in laughter at a family child-care home run by Reyes in Leimert Park.

(Ronaldo Bolanos/Los Angeles Times)

Leaders in the child-care industry fear progress will backtrack.

“It’s really anxiety-producing because it brings a lot of advocates back to those recession-era days where spaces were dramatically cut,” she said, referencing the economic downturn that led to the elimination of 110,000 subsidized child-care slots beginning in 2008.

Although California stepped up to lessen the blow, the threat of federal cuts also worsens the outlook.

As the budget proposal moves forward, the state must also brace for federal child-care cuts. A federal judge extended a temporary block on the Trump administration’s move to freeze $10 billion in child-care funds after alleging “potential for extensive and systemic fraud.” That includes about $1.4 billion in California, which accounts for roughly a quarter of the state’s child-care funding, according to the Legislative Analyst’s Office.

This article is part of The Times’ early childhood education initiative, focusing on the learning and development of California children, from birth to age 5. For more information about the initiative and its philanthropic funders, go to latimes.com/earlyed.