Laundry. It never ends.

That simple truth is a drag for most people. For Mistie Osterhage, it is a dream come true.

On a recent January morning she was in flow state, zipping around her laundry room, loading and unloading the washing machine, folding jeans and socks, moving through the tasks with calm focus as she answered questions about how she works.

“Primarily I just stay home all day and process, process, process, which is my dream job, because I love being home,” Osterhage, 47, said. That morning’s deliverable was four orders that had to be returned to La Jolla, Point Loma and Pacific Beach by 8 p.m. Her husband, Steve, would drop off those orders and pick up the next round.

It. Never. Ends.

The Osterhages are some of the roughly 200 laundry providers in the San Diego area who offer services through Poplin, the fast-growing peer-to-peer app started in 2018 by a Baltimore man (and his tech savvy son) who heard his wife’s complaint about laundry and turned it into a business.

Steve Osterhage moves dry jeans out of the dryer at his at home laundry business in Clairemont. (Zoë Meyers / For The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Steve Osterhage moves dry jeans out of the dryer at his at home laundry business in Clairemont. (Zoë Meyers / For The San Diego Union-Tribune)

“She was home with our five kids, buried in laundry, and she said, ‘This is ridiculous,’” said Mort Fertel, Poplin’s co-founder and CEO. He continued relaying his wife’s lament, saying, “‘I can tap an app to get to the airport, FaceTime with someone on the other side of the world, but I’m still doing laundry like my grandmother.’”

Fertel added his own take. First, that his wife was right, “as always.” (His other job is leading marriage boot camps.) Second, it was time to revolt. “Technology has transformed every aspect of our lives, making it all so fast and easy, except for this chore that takes the longest and we hate the most. It’s actually shocking, when you think about it. We’re in the middle of this technological revolution, and yet there’s been no innovation in this space since the washer and dryer, 100 years ago,” he said.

Poplin is now in more than 500 cities and processes more than 10 million loads a year, Fertel said. In and around San Diego, one of Poplin’s largest markets, Poplin has around 2,000 customers and has processed around 460,000 pounds, a company spokesperson said. (For scale, that’s the weight of about two blue whales, or a little more than what the Statue of Liberty weighs.)

Most of Poplin’s providers are work-from-home mothers, Fertel said. “Most of the customers are also women, and most of them are also moms. So what’s really interesting about the Poplin user community is that it’s moms helping moms,” he added.

Beyond “moms helping moms,” the app is monetizing domestic labor that would otherwise go unpaid, said Elizabeth Campbell, an assistant professor of management at UC San Diego’s Rady School of Management whose research includes gender and career progress.

“In some ways, domestic labor has been outsourced for decades, even centuries,” she said. “We have lots of information about wealthier households, who would outsource a lot of their domestic labor to servants, and they used to call it the help, right? And so to some extent, that has been happening for a very, very long time. Now we’re doing it through an app.”

Converting something like laundry to a paid task from an uncompensated household chore has several effects, Campbell suggested. As unpaid housework and child care have fallen more on women’s shoulders in homes where women and men both work outside the home, outsourcing that domestic work “could free up some opportunities for women who are still disproportionately shouldering this responsibility.” And with AI leading to job losses for white-collar workers, jobs that are not seen as “glamorous,” such as doing laundry, can be a path to “good money,” she added.

On the other hand, if the women doing that outsourced work are contractors or gig workers, they benefit from flexibility but lack the benefits of a full-time job.

Women in the post-pandemic labor economy have left the labor force at a greater rate than men have, she added. “There are two sides to this coin. In some ways, it’s good that women are finding ways to supplement their income” with gig work, she said. “But, at the same time, we don’t know what other career options they may want to pursue. The flexibility of gig work is useful for balancing home demands with work, but it has its own limitations for career growth and financial stability.”

From gigs to a leading small business

Poplin’s laundry professionals fall somewhere between gig workers and small business owners. They decide where and when to work, what products to use and how to pick up and deliver the goods. Poplin handles marketing, customer service, its membership and payment platform and pricing. It takes a 25% cut of the price per pound, which is $1 in San Diego and most other U.S. cities. Turnaround is the next day, with higher prices for faster service.

“It’s like having your own business, but they’re handling the hard stuff,” Osterhage said.

Osterhage was a stay-at-home mother years ago, when her kids were young. Later, she worked part-time, then full-time, as an elementary school health care and instructional worker.

She still did the laundry.

Then the pandemic hit. She moved from Calabasas to San Diego, where her husband had grown up. “He just always wanted to move back home,” she said.

She switched to gig work. Elder care. Walking dogs. Driving kids to school. Delivering packages. “Every app you can think of, I think I had it at one point,” she said.

To keep track of all the gig apps she used, what else, a note-taking app.

She tiptoed into Poplin about three years ago, taking one or two orders a day and folding laundry on a spare bed. As that picked up, she dropped the other gig work, added her husband as a team member, converted the bedroom to a laundry room and bought a second dryer for around $300 from Amazon.

Now the couple earns on average $2,000 per week, before deductions.

Monthly costs include $400 for laundry-related utilities and an estimated $200 for detergent, dryer sheets and laundry bags. The hybrid Toyota Corolla used for deliveries gets 45 miles per gallon, and gas for those trips costs $150 a month. Those expenses, plus investments like shelves and the second dryer, are all tax write-offs, as is the laundry room.

The Osterhages aren’t just one of Poplin’s many providers. They are its best. In their converted one-car garage, they run the top-rated Poplin account in the country. Providers get points based on starred reviews, meeting requirements and a lack of complaints. The Osterhages’ more than 322,000 points indicate customers love how they do things.

A few tricks of their trade: They are highly organized. With the washer running sometimes 15 hours a day, labels keep the loads straight and they use different bins for different steps in the process. (They schedule in their own laundry between paid loads. “It all gets scheduled,” she said.)

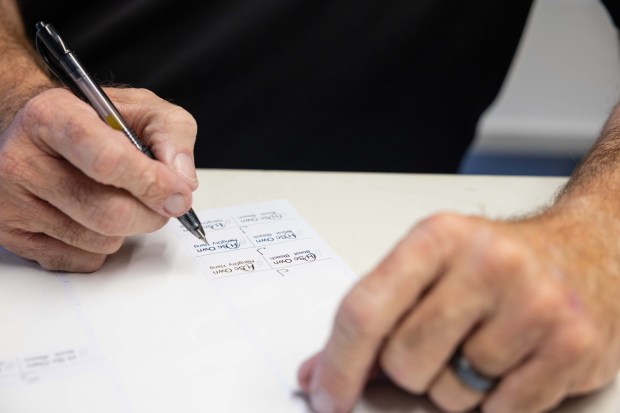

Steve Osterhage makes notes on labels at his at home laundry business, through Poplin. (Zoë Meyers / For The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Steve Osterhage makes notes on labels at his at home laundry business, through Poplin. (Zoë Meyers / For The San Diego Union-Tribune)

They customize things, to a degree. They offer a choice between Kirkland standard and hypoallergenic detergent, or people can send in their own supplies.

They build connections with regulars, who include a physical therapy office, families, and people with no in-home laundry machines. They send a baby gift to clients when they notice maternity clothes mixed in. They gave a plant to someone who had a death in the family. Top customers get Starbucks gift cards at the holidays.

They carefully curate their customer list, slashing clients who are picky, rude, too dirty (“Overwhelmingly full of dog hair. Terrible odors might be a thing,” Osterhage explained) or stingy with tips.

“We don’t take anyone under 20%. That’s our cutoff,” she said, of tips. Even as tipping is seen as optional in more and more settings, the Osterhages have more than enough clients willing to pay. “We’ve got customers that tip 150%,” she said. Clients also hand them generous Christmas bonuses, including $100 bills. “Very blessed,” she mused.

Efficiency = simplicity plus teamwork

One key that makes their business run well is simplicity.

Working on multiple apps meant losing energy to that friction. Keeping track, scheduling, managing accounts, making it all fit.

“It just was too crazy,” Steve Osterhage said. “By focusing on one thing, we could put more hours into it and make it more efficient, and that increases the dollar per hour.”

Another key is teamwork. When Steve, 63, joined Mistie, he made the process more efficient in other ways, using his know-how from running an aquarium maintenance business for 40 years. He plans the routes, added labels and he does all the administration — scheduling, recordkeeping, logistics.

Laundry never ends, but the number of orders they accept ebbs and flows. “You could have 13 (orders) one day and three the next,” she said. On a busy day, the washing machine runs 15 hours — though it’s not all active, hands-on time. A few days ago, she finished at 1 p.m. The day before, 7 p.m. “On a slow day, we go jump in the kayak,” she added.

They take one week off every quarter to travel and don’t work Saturday afternoons and Sunday mornings. That time off is a new perk. Until late 2025, they worked seven days a week.

To protect Mistie’s back, which is fragile after back surgery and a chronic disc issue, they set up a counter-high workspace for folding. “We’re very careful as far as that goes,” she said, about her back. Steve picking up and delivering orders is one more way she protects her back. Having his help is “amazing,” she said.

Steve also expressed appreciation. “All the credit goes to God,” he said.

Competing to lighten the load

There’s a reason we call a load of laundry a “load.” You drag around pounds of textiles, sort them, drop them into one machine, then another, then sort again, then fold and carry back to drawers or shelves. And that’s the easy version, thanks to modern engineering. No lye and river rocks required.

To lighten the load, companies, some using a peer-to-peer model, are sprouting up — some in local markets and others covering wide terrain. There’s Laundr, Rinse, 2U Laundry and Hampr. Hamperapp and San Diego-based Lndry are available here.

Mistie Osterhage uses stickers noting her No. 1 rating in the Poplin app on bags of clean laundry. (Zoë Meyers / For The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Mistie Osterhage uses stickers noting her No. 1 rating in the Poplin app on bags of clean laundry. (Zoë Meyers / For The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Poplin’s investors include venture capital firms and the angel investors Max Mullen, the co-founder of Instacart, and Matt Maloney, the founder of Grubhub. It raised $10 million in seed capital.

For Fertel, Poplin isn’t just about “simply laundry.” It’s about quality of life.

“We like to joke that there’s always been three things certain in life: death, taxes and laundry. So Poplin solves (one). It’s beautiful. Just tap the app, put it outside your front door and you’re done. You go on, enjoy your life,” Fertel said.

Laundry pros also get a better quality of life, he said, because “they get this unique opportunity to work from home without being tied to a desk. And many of them would otherwise not have the opportunity to work from home. Or they would have to go to work outside the home, which would not be preferable to them.”

Fertel said fixing laundry is not that different from fixing marriages.

“People sometimes joke that I went from saving marriages to saving people from their most dreaded chore. The truth is, the through line is the same: better quality of life,” he said. “Laundry is one of the biggest recurring stressors in a household. Money is another. Poplin sits at the intersection of those two pressures — we remove the chore that quietly strains one family (the customer), and create flexible income that relieves financial stress in another (the Laundry Pro). In that sense, we’re not just moving laundry around — we’re shifting weight off families’ shoulders on both sides of the marketplace.”