Get Starting Point

A guide through the most important stories of the morning, delivered Monday through Friday.

For three dollars, Americans could create a meal using “pork, or eggs, or whole milk, or cheese, tomatoes, other fresh and frozen fruits and vegetables, whole grain bread, corn tortilla,” Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins said at a news briefing after the guidelines’ debut. Calley Means, special adviser to health secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., shared a post on X comparing the cost of two Walmart grocery hauls — with a guidelines-approved basket featuring ground beef and full-fat yogurt coming out cheaper than one stocked with ultra-processed foods the guidelines discourage.

At the same time, some nutrition experts have criticized the prominent placement given in the guidelines to beef and beef tallow — foods that are not only higher in saturated fat, but also more expensive than chicken and plant-based sources of protein like beans and tofu.

Both camps have valid points, according to food economists and nutrition experts who spoke with STAT. Overall, the MAHA agenda of eschewing ultra-processed foods is an affordable one, said Masters, a professor at Tufts University. “When you choose the least expensive options in food groups to meet dietary needs, you go with whole foods,” he said. Plain dairy products, canned beans, and tinned fish pack a lot of nutrients at a relatively low cost.

On the other hand, Masters noted, the pyramid also features pricey shrimp and ribeye steak at a time when beef prices are up 16 percent from a year ago. And the guidelines’ recommendations that people more than double their protein intake compared to previous standards would likely increase spending, said Joelle Johnson, deputy director for healthy food access at the Center for Science in the Public Interest.

“That recommendation, along with choosing higher-fat dairy, would likely have the biggest impact on a person’s food expenses if they were to follow it,” Johnson said via email.

Ultimately, the costs and nutritional impact of the new guidelines vary based not just on where Americans live and shop, but how each individual might interpret the new guidelines. Still, as a thought exercise, STAT found a food economist and registered dietician who used Masters’ spreadsheet to calculate the costs of a couple versions of a MAHA diet — both financially and nutritionally. To understand the results, it’s helpful to take a step back to explain what nutrition experts mean when they talk about affordability, and why it matters for Americans’ health.

What affordable food really means in the US

Food prices are up 27 percent compared to five years ago, said Michigan State University food economist David Ortega. Forces including the COVID-19 pandemic, bird flu, droughts, tariffs, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and flesh-eating screwworms, among others, have all combined to increase the cost of beef, eggs, and other sundries.

Prices today aren’t rising as much as they were. But economists don’t expect grocery bills to go back to pre-pandemic levels, since generally, the prices consumers pay aren’t out of line with the costs of production.

“They’re expensive because labor, rent, and [other costs] are expensive,” said Masters.

What a person considers affordable will depend on their income. In the US in 2023, the lowest-income households spent about $14 a day on food, while middle-class households spent $25 and the highest-income households spent $47, according to government data. People on food benefits, meanwhile, receive an average $6 a day per person to spend on food.

Affordability is also about more than how much you pay at the grocery store, say nutrition experts.

“When you’re trying to assess the cost of whether people can afford food, the most important is the time cost” — how much time people spend planning meals, acquiring ingredients, and preparing them, said Jerold Mande, who worked as a policymaker under three presidential administrations and currently heads the nonprofit Nourish Science.

A one-pound bag of dried chickpeas, for example, is nutritious and costs less than $1.50 at Walmart. But before they’re ready to eat, they have to be soaked for at least an hour (some prefer overnight), then cooked a couple hours on the stove over low heat, then combined with other ingredients — presumably ones that require some preparation of their own — into a complete dish.

It’s true that there are plenty of nutritious meals that can be prepared relatively cheaply and quickly. But it’s also easy to see why a busy family juggling work, school, and childcare might grab some frozen pizza instead.

“Maybe a meal can cost three dollars, that’s not inherently a wrong statement,” said Ortega. “But those types of calculations often rely on best-case scenarios that don’t reflect how many households actually eat.”

Amelia Finaret, a clinical dietician and food economist at Allegheny College, notes that there’s another, less direct concern when it comes to affordability:

“Sometimes, more affordable items don’t taste as good to us, such as the difference between fresh and canned vegetables, which could make it less enticing to include our vegetables if we need to go with the more affordable option.”

All this means that in the fight against chronic disease, diets that are affordable as well as nutritious are a key part of the equation.

The cost of MAHA’s new protein recommendations

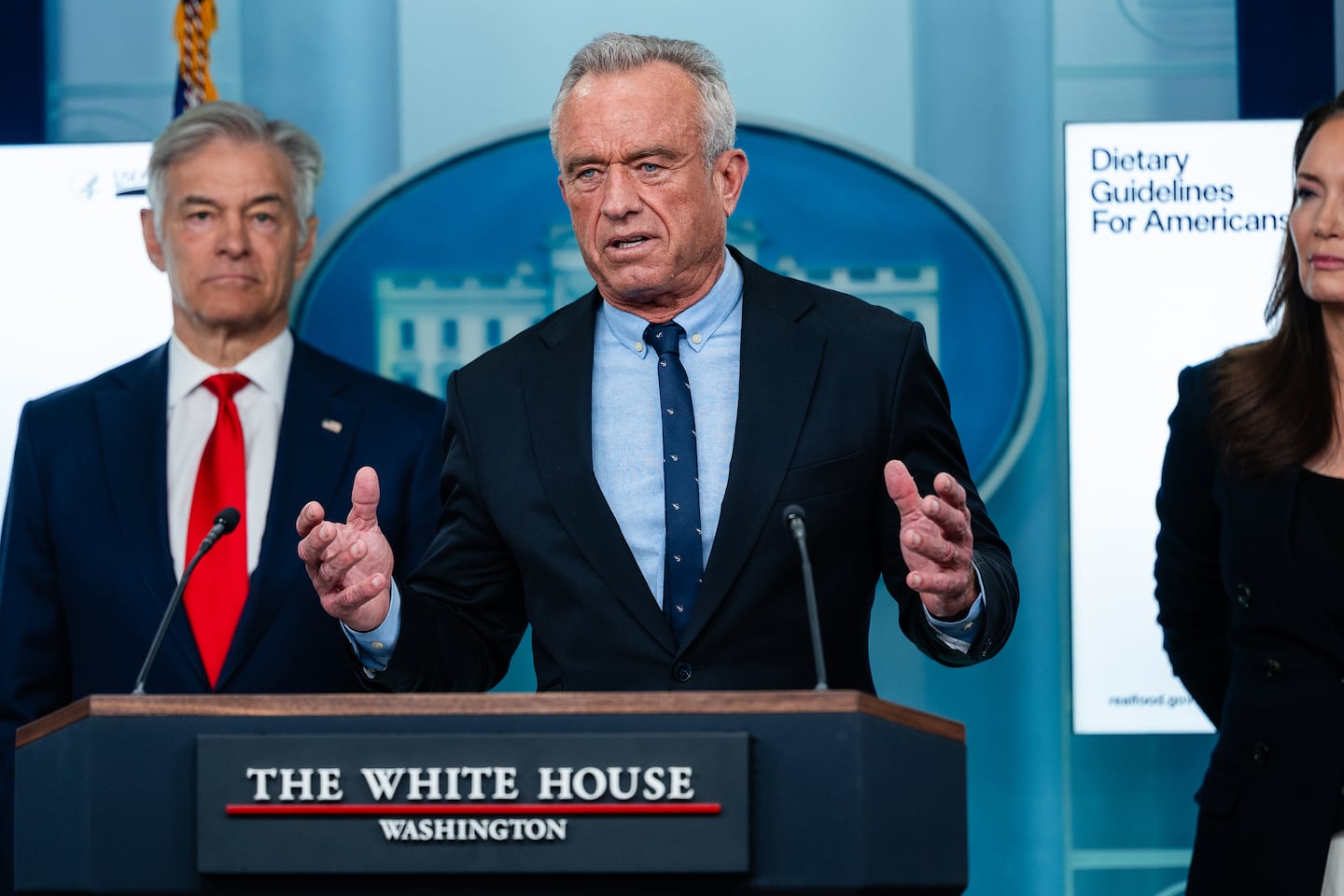

Secretary of Health and Human Service Robert F. Kennedy Jr. spoke about new dietary guidelines during a briefing for reporters at the White House in Washington on Jan. 7.ERIC LEE/NYT

Secretary of Health and Human Service Robert F. Kennedy Jr. spoke about new dietary guidelines during a briefing for reporters at the White House in Washington on Jan. 7.ERIC LEE/NYT

Many experts cheered the guidelines’ strong stance against ultra-processed foods, with Masters praising the administration’s apparent willingness to stand up to major food manufacturers. There are other bright spots, too. The new food pyramid features a bag of frozen peas. Frozen vegetables are often cheaper than their fresh counterparts.

On the other hand, Finaret worries about people spending money on protein they don’t need.

“Most adults who are not critically ill and who are not elderly and losing muscle mass don’t need more than about 0.8-1 gram per kilogram of body weight,” she said. The new guidelines recommend 1.2-1.6 grams of protein per day per kilogram of body weight. (For a 150-pound person, that would be 109 grams of protein at the high end of the range, equivalent to about 18 eggs or four chicken breasts.)

But unlike fats or carbohydrates, “we can’t really store protein in our bodies,” Finaret said. “I don’t know where all this protein is going to go or why you would buy it, because it seems pretty wasteful.”

Eating by the new food pyramid

Finaret was game to test out the new MAHA guidelines using Masters’ spreadsheet, which tallies up the cost per day of a diet that aims to meet daily recommendations for nutrients like protein, fat, fiber, and calcium. It’s based on online grocery prices at Stop & Shop in Boston, which he often used as a classroom exercise for helping his students at Tufts University understand the costs of adequate nutrition.

In designing two versions of a daily diet for a 30-year-old woman, Finaret explained, “I tried to meet the new protein guidelines and have two servings of fruit, three servings [of] veggie, and three servings [of] whole grains, just like the new pyramid advises.”

For her first version, she said, she wasn’t trying to keep costs as low as possible — just choosing foods she thought she’d like to eat. She included servings of beef and blueberries, and aimed for about 90 grams of protein based on the new recommendations. She also chose chicken breasts over the cheaper chicken thighs. Her total cost per day: $8.59. The second time, she tried to keep costs down as much as she could while staying within the guidelines’ recommendations. She chose canned tuna and chicken thighs, apples and bananas, frozen peas, cabbage, and canned green beans. Total cost: $5.08.

Nutritionally, Finaret said, there was at least one big problem. She wasn’t getting enough energy (she’d need around 2,300 calories) to maintain her body weight. “Two to four servings of grain is insufficient,” she said. “I don’t think people know how small a serving of grains is” — equivalent to one slice of bread, or six Triscuits.

The more expensive diet did a better job of meeting her micronutrient needs, though vitamin E and calcium were still pretty low.

Overall, Finaret wouldn’t recommend that her patients adhere strictly to the new guidelines, especially because of their emphasis on animal proteins and her concerns about relying too much on produce rather than whole grains for fiber. Also, she said, “I wouldn’t be able to ask my patients to spend that much money.” If one person is spending $8.58 on food each day, she said, for a family of five, that’s $300 a week. That’s a lot for people on a budget.

The good news, she said, is that most people can spend less food and have healthier diets in the process, particularly if they focus on plant-based proteins like beans. That’s especially true if people stop spending so much money on unnecessary supplements and alcohol. Notably, the new guidelines actually feature weaker language about limiting alcohol consumption.

The upshot, according to Masters, is that some parts of MAHA’s new guidelines are both affordable and nutritious, and some aren’t.

“That’s a characteristic feature of the movement, “ he said, “where it’s rebelling and declining to follow consensus. Sometimes that provides a breakthrough that’s really helpful, and sometimes it’s just incorrect.”

STAT’s coverage of chronic health issues is supported by a grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies. Our financial supporters are not involved in any decisions about our journalism.