Keep up with LAist.

If you’re enjoying this article, you’ll love our daily newsletter, The LA Report. Each weekday, catch up on the 5 most pressing stories to start your morning in 3 minutes or less.

Del Rey resident Devora Roberts says she often has difficulties knowing who to call for city services like tree cleaning and trash pick ups.

The area, a neighborhood on the westside along Washington Boulevard, jaggedly straddles the border between Culver City and the city of Los Angeles. She says the area’s “wacky” boundaries had got her and her neighbors intrigued.

“ This kind of all made us think about what was this neighborhood before,” she said.

She and her husband did some digging and discovered it had once been its own city: Barnes City. And more — it had been the home of a huge traveling circus.

When she emailed me with its fascinating history, I knew I had to find out more.

A reason for cityhood

Most of the 88 cities in L.A. County are pretty old, some going back more than 100 years. One by one, this scenario repeated itself: Residents got behind the idea of forming a city, a municipal government got elected and the area grew.

But like a fast blip on radar, a handful barely got off the ground.

That’s what happened to Barnes City.

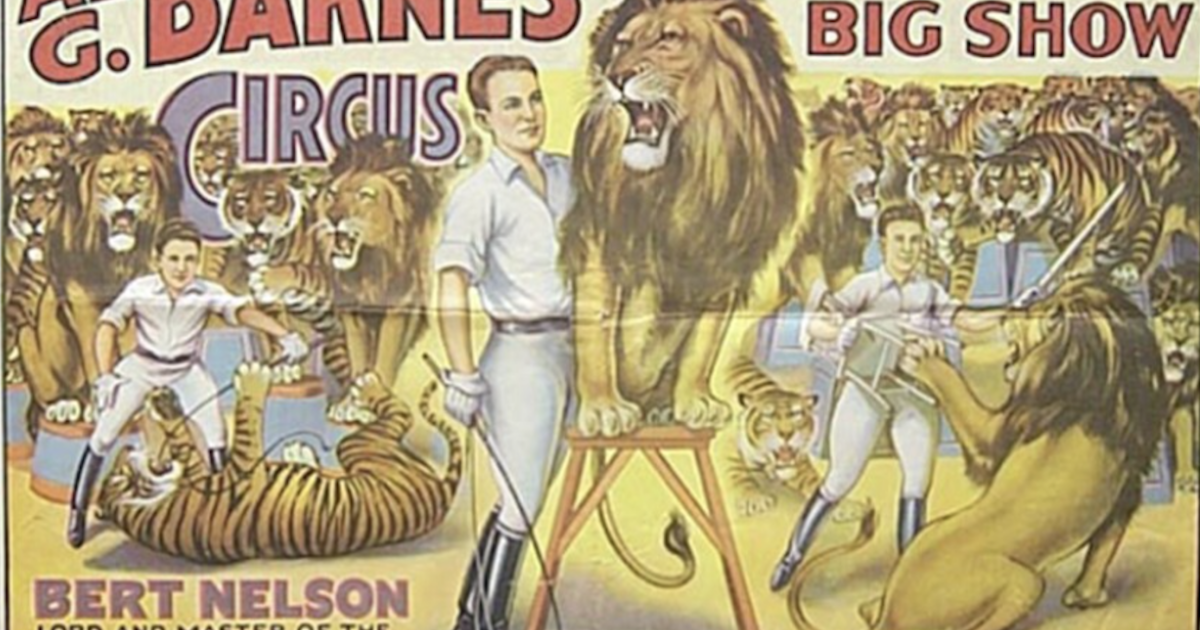

In the early 1900s, the area was simply ranch land before being purchased by Alpheus George Barnes Stonehouse, who ran the immensely popular Al G. Barnes wild animal circus and zoo, said to have “1,000 performing animals.”

The entertainment offered was the kind you’d expect in those days: zebras dressed up as clowns, elephants reenacting battlefield scenes and daring human stunts. One “girl trainer” would enter a cage of 30 lions and feed them strips of raw meat with her teeth, according to newspaper reports of the time.

A flyer for Al G. Barnes’ 1,000 animal circus, paired with a portrait of him.

(

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

)

Shows reached as far as Canada and as close as Pasadena and Long Beach. During the winter offseason, the circus stayed around L.A. County. And at the end of the 1920 season, Barnes moved the circus’ permanent winter quarters to his ranch land. The homes and later local zoo were by the corner of Washington Boulevard and McLaughlin Avenue.

An undated aerial view of the entrance and layout of Al G. Barnes Circus, headquarters and zoo located near Culver City.

(

Security Pacific National Bank Collection/Los Angeles Public Library

)

While the land was unincorporated, it was right next to the border of the newly created Culver City. (In fact his animals were regularly hired out for the growing number of movie productions there.)

That’s where the circus staff and animals would stay, relatively without issue, until Culver City came knocking in 1925. The city was looking to expand its boundaries and had begun the process of annexing a swath of his land. Barnes tried to stop it in court, arguing it would affect the value of his property and that his front porch would be in Culver City limits while his sleeping rooms would be outside of it.

The circus’ facade advertised its large animal shows, Tusko the elephant and Lotus the hippo.

(

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

)

To get around the annexation, Barnes petitioned the L.A. County Board of Supervisors to permit the area to become its own municipality, to be known as Barnes City.

After much legal and political wrangling, county supervisors set an election in February 1926 for the area’s roughly 400 registered voters, which included much of Barnes’ staff. Cityhood passed with 145 voting in support and 128 opposed.

The ‘political war’

Once the city became officially recognized on Feb. 13, 1926, elected trustees took office. Among those were Barnes’ allies, including his brother Albert T. Stonehouse, who became mayor. But it took less than a month for problems to brew.

Another group of residents, the La Ballona Improvement Association, were unhappy that Barnes’ name — and the name of the circus — had become the moniker of the city. They’d already unsuccessfully challenged it with the L.A. County Board of Supervisors, claiming it would negatively label the area as “Monkeyville.”

This group, and other factions against Barnes, pushed to have a second city election on April 12 in line with state regulations.

During this time, Barnes had been out performing. So he moved his entire circus back home for a one-day stint to allow his 350 performers to vote.

It was a tight race, but it ultimately went against him. Almost all of Barnes’ opponents won official city roles like trustee and city attorney.

Many residents felt there was only one way to deal with the issue of Barnes City: eliminate it and become part of another city. They opposed becoming part of Culver City because of its onerous regulations, but joining the nearby city of L.A. was another option.

So in September 1926, residents voted to merge with Los Angeles.

Barnes City had lasted a mere seven months.

For Roberts, learning the history has been eye-opening.

“ All of us complain about the fact that we don’t know if we’re supposed to call Culver City or L.A.,” Roberts said. “But knowing why that happened is useful. At least it gives us some context.”

It also gives her something to search for. On Roberts’ walks, she likes to look for spots that could’ve been interesting fixtures in Barnes City, like a ticket office or an elephant area.

“ I think it’s part of the funny, quirky history of Los Angeles,” she said.