“The only thing that you absolutely have to know is the location of the library.”

That’s a quote often attributed to Albert Einstein, though it’s probably apocryphal. Regardless of who said it, this reporter believes it. If you do too, you’re in luck — because there are probably more libraries in the county than you think there are. But you’d be forgiven for missing them.

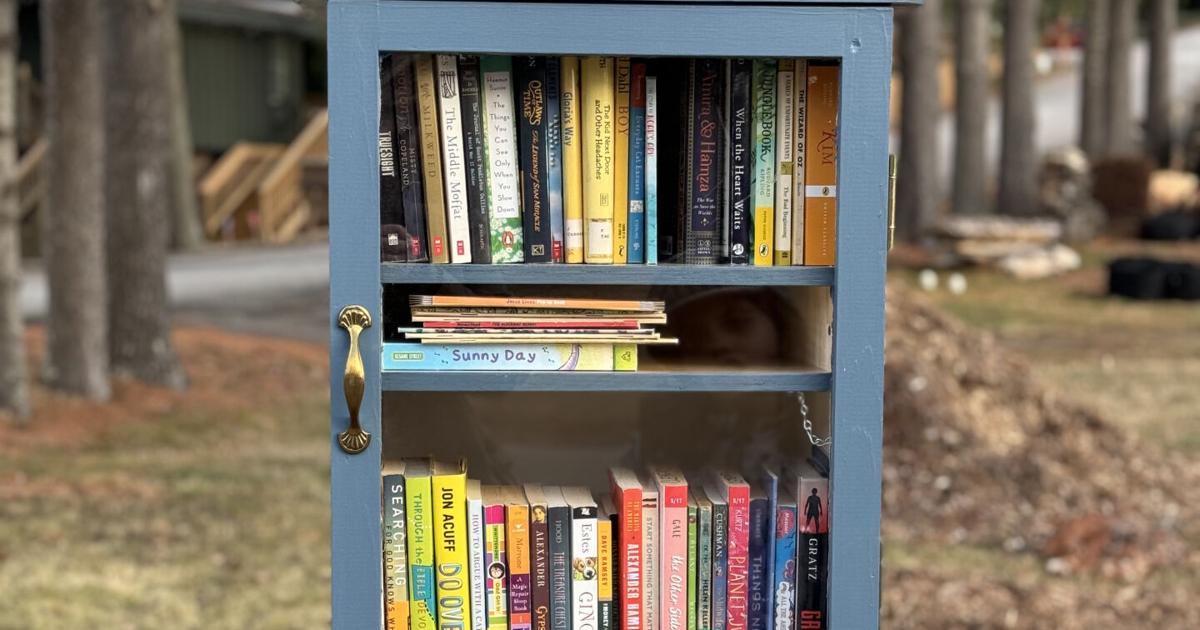

Tucked away next to playgrounds, huddled outside of businesses, standing in front lawns, and inhabiting other odd little corners of the county, Little Free Libraries are exactly what they say they are. Often slightly larger than a milk crate, freely available for any passerby to browse, and stocked with books by whatever noble soul put them up in the first place, they exist as a monument to the simple joys of the written word.

But that’s a joy that’s shrinking in American culture. Federal data points to sustained drops in reading and book ownership across virtually every demographic. Statistics on childhood literacy are even more troubling, with the National Assessment of Educational Progress reporting that 69% of fourth graders and 70% of eighth graders read below their grade level.

The tiny congregation of Maple Grove United Methodist Church, on Russ Avenue, isn’t going to stand for that in Haywood County.

Joyful hearts and prayerful missions

The church, like the libraries it peppers around the county, is small but mighty. There are 100 members on the roll but around 50 folks show up on any given Sunday. The congregation might be far from mega-church numbers, but that didn’t keep it from conducting an intensive study to see how it could best serve the county — a study that ended up convincing the members that childhood literacy would be their issue of focus.

“And in that process, we determined that free little children’s libraries would be a great way to address part of this problem,” said Barbara Timmington, who heads up the program for the church.

Two years later, and Maple Grove has placed libraries at the Waynesville Kiwanis Community Playground, Clyde Elementary, Clyde Central United Methodist Church, and, most recently, at the Maggie Valley Town Hall Park and Playground. Three locations across Bethel and Canton are in the works.

Allan Watts builds the libraries for the church, working off plans he was handed when he agreed to take on the project. The results are cheerful red and white boxes with steeply angled roofs and glassed-front doors showcasing the plethora of children’s books contained within. Sometimes the libraries are adorned with a wooden cutout of a bookshelf, or children playing. For Watts, the work’s reward is self-evident.

“It fills my heart with joy to be able to be a part of it. It’s great to see the kids when they are getting books, and they’ve got big smiles on their faces. It brings joy to mean something in some little child’s life, to brighten their day,” he said. “Giving the kids access to something that they may not have readily available.”

In memory of Anna

But before the libraries can be used, they have to be stocked. That’s where Dana Smith comes in. The long-time educator runs Anna’s Books — a non-profit that Smith says is the largest children’s book bank in Western North Carolina.

Anna’s Books is a resource for elementary school teachers, parents, and children region wide. Smith says anyone is welcome to take what they need — it’s all part of carrying on the memory of Anna Williams, the former principal of Meadowbrook Elementary School in Canton.

Williams passed away due to complications from the birth of her daughter in 2013. A few years later, Smith married Brian, Williams’ widower, and wanted to do something to honor the woman’s life.

“Her death was still very looming and still very raw and painful, and I wanted my kids to be happy. I wanted my kids to see both of their moms doing good things and not to be sad about it. So we would do Anna’s Birthday Book Bash at Meadowbrook, where we would come and give the teachers books,” Smith told The Mountaineer. “And then it just kept growing and growing and growing.”

Eventually, Smith said, all the teachers at Meadowbrook had enough books — an extraordinary statement if you know anything about how much of a teacher’s diminutive paycheck goes right back into classroom supplies.

Smith moved on to other schools, then other counties. Out of the ashes of tragedy, Anna’s Books first kindled, then arose.

While funding from Grace Church in the Mountains in Waynesville allows Smith to buy hard-to-find new books directly from a wholesaler, most of her stockpile is second-hand.

“I get books left on my doorstep. I leave my van unlocked, and people put them in my van,” she said, chuckling.

Although it started in her basement, Smith now runs Anna’s Books out of Maple Grove. She distributes the books by appointment, through book fairs and events, and Maple Grove’s libraries. Another wing of the church’s volunteer force drives around with boxes of books and replenishes the libraries whenever they need topping off.

“Last year we took in about 10,000 books and we gave out about 8,500 into the community,” Smith said.

Doing good things indeed.

Power of print

Amanda Cooke is the office manager of The Mountaineer, where she spends her days attempting to organize an unruly and forgetful group of newspaper folks into some semblance of functionality. But that hasn’t always been her fate.

“I was originally an educational assistant for 10 years. The more kids see print, the better readers they become,” she said, emphasizing the word “print” as perhaps only a newspaper employee can. “Actually holding print helps them understand it and develop better than electronically seeing it.”

So Cooke built a Little Free Library out of an old Mountaineer newspaper rack and placed it outside the building next to the newspapers. She stocks it herself, using whatever books she can scrounge up from her network of friends and former educational colleagues. Unlike the libraries built by Maple Grove, this one contains books for all ages, with adult fare proving just as popular as children and young adult offerings.

“And then each book that we put in also gets a library card style bookmark,” Cooke said. It’s a fun little addition that helps people trace the tangled travels of books through the county — or possibly beyond. You never know where a book might end up.

In fact, there are over 200,000 Little Free Libraries sprinkled across 128 countries, according to the nonprofit organization of the same name that manages them. It costs about $50 to “charter” with the organization — meaning your Little Free Library is an official part of the network.

Not everybody who builds a library takes the time or feels the need to buy a charter — Maple Grove’s libraries aren’t officially Little Free Libraries — but doing so does come with benefits. Chief among them is that a registered library is searchable on the organization’s website and mobile app.

Geocaching for bookworms

That searchability is what got Hazelwood resident Emily Fleenor and her family interested in Little Free Libraries. Fleenor and her children were traveling in Charlotte when Fleenor’s aunt suggested a trip to the neighborhood Little Free Library. Fleenor’s kids were enchanted by the experience.

“So I started looking for them in other places. And then I found there’s an app. And you can use it to find libraries near you. So it’s a really inexpensive activity when we go someplace new, to look for little free libraries. It takes you into different neighborhoods, near parks and all kinds of different places,” Fleenor said.

Her family had the Little Free Library bug, and so of course the next step was building one of their own. But Fleenor’s house wasn’t in an area that got a lot of foot traffic.

“ Then a few years ago, my in-laws bought a house on Brown Avenue with the sidewalk right in front, just three or four houses down from the middle school,” she said. “And so I said, kind of offhand one day, ‘Man this would be a great place for a Little Free Library. And that Christmas, my father-in-law made one for me.”

Fleenor’s family, along with the community on Brown Avenue, keep the library stocked. And like all official Little Free Libraries, it has the slogan “take a book, leave a book,” emblazoned across the charter plaque.

That’s the way Little Free Libraries are supposed to work. But as you may have gleaned from reading this story, more often people just take a book without leaving one in return.

And that’s OK, says every person interviewed for this story. The National Center for Educational Statistics reports that 61% of children living at or below the poverty line have no books at home.

Those are stats no educator worth their salt can abide.

And if you guessed that Fleenor — like Amanda Cooke, like Dana Smith — has a background in education, you guessed right. She’s a second-grade teacher at Junaluska Elementary.

“We’re passionate about books,” Fleenor laughs when the Little Free Library/educator overlap is pointed out.

Smith, busily cycling thousands of books through the county and beyond, agrees.

“My goal is to get books into the hands of kids. It’s important for kids to own their own books and be able to choose books that they want,” she said.

“If a kid loves a book, let them have it.”