He sent federal immigration agents into Southern California communities, farms and workplaces vowing to drive “illegal aliens” back across the border.

His raids regularly netted hundreds of arrests a day and he once boasted about apprehending 70,000 people in a single month in San Diego County alone.

Newsletter

You’re reading the Essential California newsletter

Our reporters guide you through the most important news, features and recommendations of the day.

Enter email address

Sign Me Up

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

When L.A. declared itself a “sanctuary city” for Central American migrants, he vowed to have Washington cut off the city’s federal funding. He took pride in arresting undocumented workers when they showed up to collect their lottery winnings.

Time magazine once captured him surveying a crackdown on the border that netted nearly 2,800 arrests in one 24-hour period.

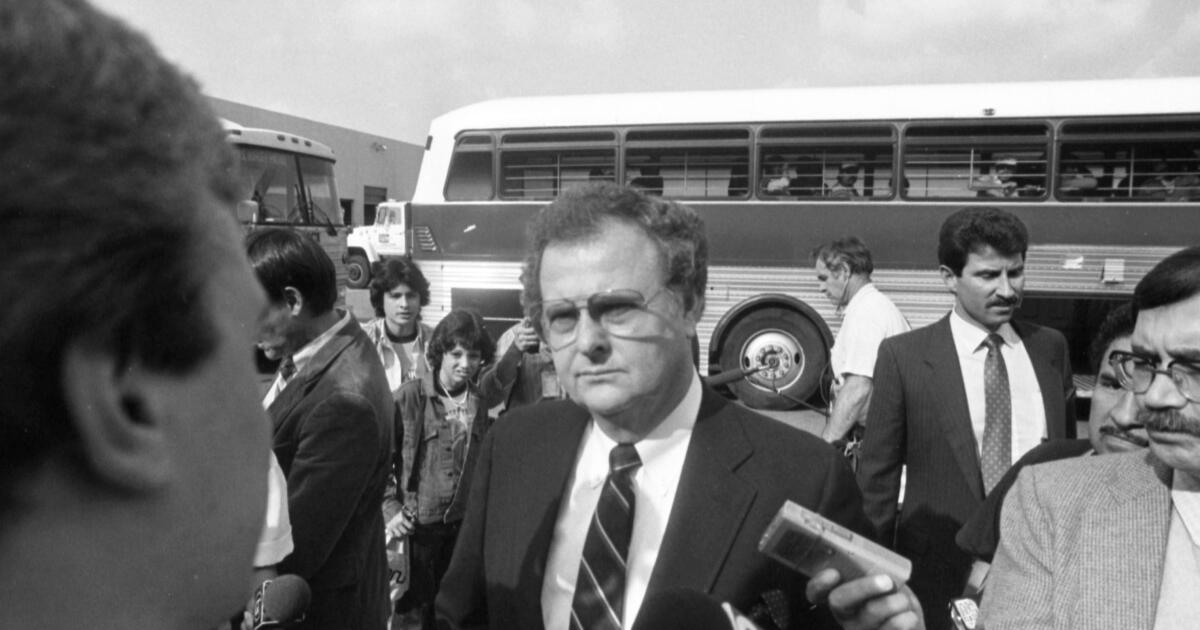

Before Donald Trump and Stephen Miller and Kristi Noem, there was Harold Ezell.

Harold Ezell

(Todd Bigelow/For the Times)

The original deporter-in-chief

Ezell was a mid-level manager in the federal immigration bureaucracy who nonetheless ran one of it — not the — biggest deportation operation in California history. His title was regional commissioner of the Immigration and Nationalization Service. But with the blessing of Ronald Reagan in the early 1980s, Ezell eagerly emerged as a national figure of both scorn and love, railing against illegal immigration and using his troops to, as he put it, turn back the “invasion” and return America to “Americans.”

“The reason why you have control of immigration is that you can assimilate a certain number of people every year into your culture, into the American way, into America, America’s lifestyle,” he once explained to Times reporter Laurie Becklund. “Already, you need to know Spanish to navigate your way around downtown.”

Ezell is a largely forgotten name in a largely forgotten immigration war.

It was an era before a powerful immigrant rights movement, before the rise of Latino politics in California. Until recently, it seemed to many like a throwback to an outdated, crude form of border enforcement we’d probably never see again.

But it’s worth considering Ezell’s war and its aftermath as we try to make sense of what’s happening before our eyes on the streets of Southern California.

Federal agents have arrested 2,800 people since the beginning of President Trump’s immigration sweeps a month ago.

It feels like a stunning number, a quantification that adds to the sense of terror and upheaval spreading across immigrant communities.

But compared to the heights of the Ezell raids, these numbers seem small by comparison.

Of course, California was a different place in the 1980s – much more white, more Republican (Reagan won big in 1980 and 1984) and, according to polling, much more concerned about illegal immigration. As late as 1993, a Times poll found a whopping 86% of respondents said illegal immigration was a problem.

Ezell is easier to understand from the prism of Reagan’s “Morning in America” era. The son of a pastor from Wilmington, Ezell made his name as an executive at the Wienerschnitzel hot dog chain before getting into Republican politics (he once quipped “It’s hamburgers that hire illegals because they have kitchens.”).

Even critics who considered his policies cruel and racist – and there were many – admitted that behind the bluster there was the charm of a true believer. There was a scorched-earth quality to his raids. The feds targeted race tracks (forcing Del Mar to temporarily close), public transit and, notably, factories with the hope employers would get the message and hire citizens. This traffic sign — showing a family running across a road —came to symbolize his era.

Harold Ezell dons a sombrero as other members of the “Trio Amnistia” look on.

(Chris Gulker)

The cycle of crackdown

But it did not take long to see a certain futility in the crackdown.

Ezell himself admitted in 1986 that all the arrests were not keeping up with the estimated 2,000 new border crossings each day. He insisted it was about sending a message. That same year, Congress passed the landmark Immigration Reform and Control Act, which gave a path to citizenship to more than three million immigrants here illegally. Ezell turned to getting the word out about amnesty, infamously donning a mariachi hat and singing “Trio Amnestia” at one event.

Ezell eventually became a major supporter of Proposition 187, the California measure that prohibited undocumented workers from receiving public assistance. The measure passed, but it began a political backlash to anti-immigration policies. Changing attitudes and demographics made California much more supportive of immigration as a benefit to the economy and the culture.

Ezell died in 1998 and did not live to see the remarkable transformation.

But as my colleague Gustavo Arellano noted in his excellent podcast on Prop. 187, the extremism of the 1980s and 1990s anti-immigration movement were also the seeds of its destruction.

I asked Arellano about all this. “Stephen Miller should learn well from Ezell, but not in the way he would like to think.” History has not been kind to Ezell, he said, and “that’s how history is already remembering Miller. It’s not too late to change that.”

This week’s must readMore great readsFor your weekend

Awan ice cream’s new Melrose Avenue flagship offers more than a dozen flavors of the fully vegan ice cream made with coconut cream and Balinese vanilla.

(Stephanie Breijo / Los Angeles Times)

Going outStaying inA question for you: What’s your favorite California beach?

William Barnes writes: “My favorite California beach is the one of my youth, Moonlight Beach in Encinitas, Calif.”

Jot McDonald writes: “Ancillary Beach. It has the whitest sand!”

Amy writes: “Easy. Huntington Beach.”

Email us at essentialcalifornia@latimes.com, and your response might appear in the newsletter this week.

L.A. Timeless

A selection of the very best reads from The Times’ 143-year archive.

Have a great weekend, from the Essential California team

Diamy Wang, homepage intern

Izzy Nunes, audience intern

Kevinisha Walker, multiplatform editor

How can we make this newsletter more useful? Send comments to essentialcalifornia@latimes.com. Check our top stories, topics and the latest articles on latimes.com.