Fort Worth’s century-old Sagamore Hill Negro School, with its slanted roof and gabled porches, has no historic marker and no sign above the door — yet it merits landmark status. Originally a four-room schoolhouse for Black children learning their ABCs, the building was constructed in 1924 with blueprints and partial funding from a Jewish philanthropist.

It is one of 464 Rosenwald Schools that opened in Texas between 1913 and 1932, years of stark racial disparities. Thirty-six of these little schoolhouses still stand in Texas in some form, many as community spaces, according to the Texas Almanac.

Fort Worth’s rare, Rosenwald School has been modernized and well maintained by the Fort Worth Independent School District, yet it hosts few educational activities. Its doors at 5100 Willie St., on the campus of the Dunbar Young Men’s Leadership Academy in Stop Six, are usually locked.

“It’s still used, but not to the degree it could be,” according to former Fort Worth City Councilman Frank Moss, 79, one of the school’s alumni. He and his four brothers attended the school house in the 1940s and 1950s. He views the landmark as a time capsule that teachers and students should visit on field trips to envision the past.

“Our Rosenwald School grew out of the Black churches,” said Moss, president of the Center for Stop Six Heritage, which has an office in the building. “It has a proud story to tell.”

Former Fort Worth City Councilman Frank Moss on the porch of the former Sagamore Hill Negro School, which he and his brothers attended when public schools were racially segregated. The building, which is the size of a portable classroom, is on the grounds of the Dunbar Young Men’s Leadership Academy at 5100 Willie St., the exact spot where the original wood frame schoolhouse was constructed in 1924.

An exhibit running until Aug. 17 at the Dallas Holocaust and Human Rights Museum, “A Better Life for Their Children,” tells the history of the Rosenwald Schools. They grew out of a partnership between Julius Rosenwald, president of Sears & Roebuck, and Black educator Booker T. Washington, author of “Up From Slavery.” Their collaboration led to the construction of 4,977 rural school buildings in 15 states where Black youngsters learned to read, write, add and subtract.

During the Jim Crow era, if Black children went to school at all, it was often in crude shacks with rickety desks, torn textbooks, broken pencils and no chalkboards.

In Fort Worth’s Stop Six neighborhood, two churches — Prairie Chapel and Cowan McMillan African Methodist — provided school rooms for African American youngsters. In 1921, farmer Alonzo Cowan donated land on Willie Street for a future Black school.

Three years later, on April 12, 1924, the Sagamore Hill ISD held a controversial election to allocate $5,000 in bond money for a Black school house. With 55 percent of the vote, the measure passed. Using blueprints supplied by the Chicago-based Rosenwald Foundation, construction began. Black families pitched in on the work. The building opened in the fall of 1924 with R.H. Hines its principal.

By then, Sagamore Hill schools had been incorporated into the Fort Worth school district. Superintendent Burl Carroll, whom the Ku Klux Klan had endorsed, inspected the premises along with an instructional superintendent from Austin. The latter approved an additional $1,100 from the Rosenwald Fund to furnish and finish out the building.

Rosenwald Fund established by Russian Jewish immigrant

The Star-Telegram mistakenly reported on Sept. 25, 1924, that the Rosenwald Fund was established by a wealthy Black person from Chicago, rather than a Russian Jewish immigrant with a nationwide mail-order catalog.

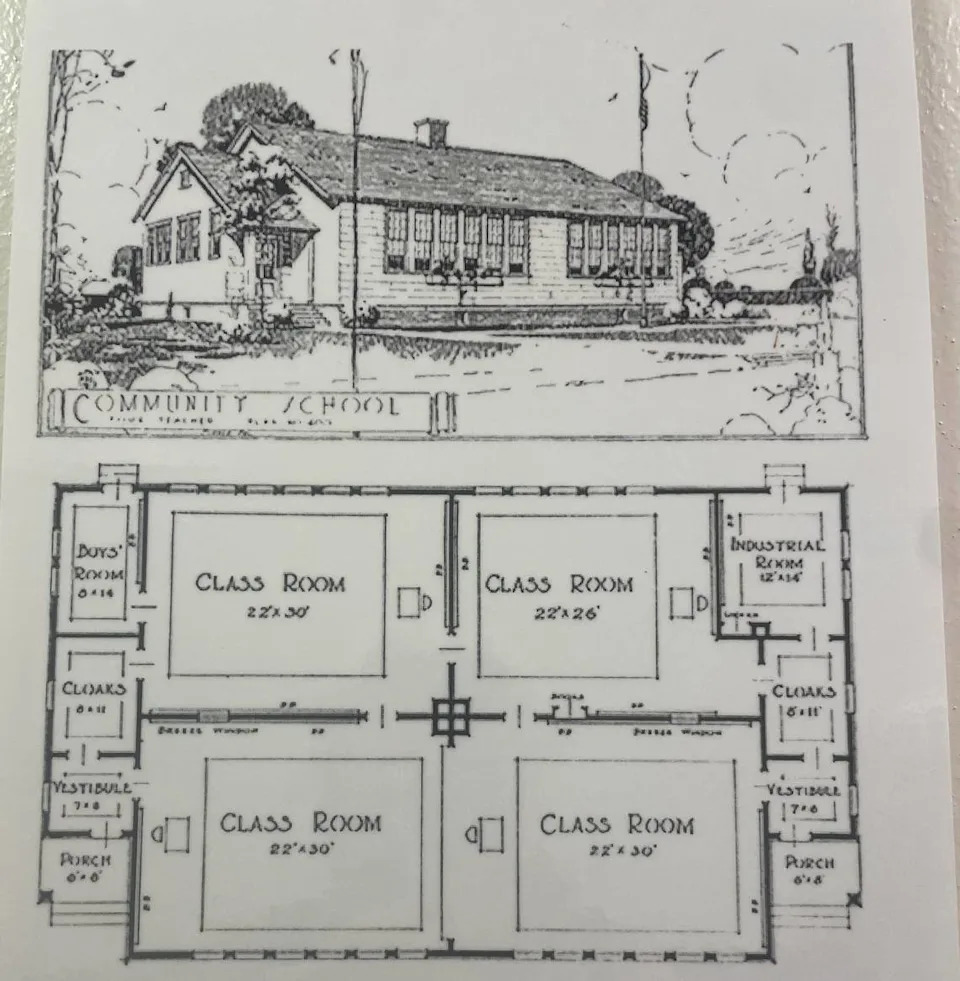

The original Sagamore Hill Negro School had four classrooms — three measuring 660 square feet and a fourth with 572 square feet. A small vocational room was 12 feet by 14 feet and focused on agriculture. That space was the FWISD’s only “industrial” room for Black students. White schools had “day trade” classes that included auto mechanics, printing, cabinetry, electrical wiring and machine shops.

The sketch and floor plan of the Sagamore Hill Negro School are posted on the wall inside the building, where Frank Moss periodically leads tours about the history of Rosenwald Schools and the Stop Six neighborhood.

The Sagamore School had no indoor plumbing. “I remember when I went to school here, we had outdoor toilets,” Moss recalled.

Because it lacked electricity, it was designed with more than two dozen vertical windows that let in natural light and a breeze.

“The rooms were bright with sunshine,” Moss said. “They were hot but well ventilated.”

The segregated school had wooden walls, inside and out, and wood floors. During its first five years, classrooms filled with elementary students. On Sept. 8, 1931, the Star-Telegram announced that enrollment had grown so large that the school would have to accommodate students up to seventh grade.

In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that integration of public schools was the law of the land. The FWISD resisted. For more than three decades it fought lawsuits filed by the NAACP and Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund. Moss and his brothers remained in segregated public schools.

Frank Moss graduated from the all-Black Dunbar Junior/Senior High in 1964 and enrolled at the University of Texas at Arlington. For the first time, he sat in classrooms with white students. Ultimately, he earned a bachelor’s and a master’s degree from UTA. He completed post-graduate work at Harvard University.

School preserved after desegregation

When complete desegregation finally came to the FWISD, the historic Rosenwald School was not forgotten. In was modernized in 1978-1979. Updates included a handicap-accessible entry ramp, aluminum siding and new windows. The vocational room was converted into restrooms.

The modernized version of the former Sagamore Hill Negro School has fewer windows than the original and is covered in steel siding, which would likely disqualify it from being listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Nowadays, blue carpet covers the original wood floor. An air conditioner hums. Walls are painted pale yellow. Instead of classrooms, the building’s interior is a large, inviting meeting room with a circular reception counter in the center. At various times, the building has served as an alternate school and a branch of the school district’s Family Action Centers.

Several modern updates — such as aluminum siding — would likely disqualify the building from being listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It could, however, become a registered Fort Worth Landmark, because it is the site of historic events illustrating the social, economic and ethnic heritage of the city. Landmark status would impose a 90-day demolition delay should the school district decide to move or demolish the school building.

The school would qualify for a bronze marker from the state. The Texas Historical Commission has made an ongoing effort to identify, document and award markers to Rosenwald Schools.

Hollace Weiner, an author, archivist and director of the Fort Worth Jewish Archives, was a full-time Star-Telegram reporter from 1986 to 1997.