Moises Saman won two Pulitzer Prizes for photography in May. One was in the Feature Photography category for his coverage of Syria after the fall of dictator Bashar al-Assad, which he undertook for The New Yorker. The other was in the International Coverage category, as part of The New York Times team covering the war in Sudan.

In a video call with EL PAÍS from his home in Jordan, the 51-year-old Samán explains that he came to his profession by chance. He was born in Lima, Peru, moving to Barcelona at the age of two. And, in his teens, he moved to the United States. There, he distributed phone books, washed dishes and waited tables in restaurants. Without fully understanding English, he randomly enrolled in a sociology program at a college “where they let anyone in.” And there, he saw them: several photos of the then-active Yugoslav Wars that his professor showed him. “I reacted to that,” he recalls.

Today, he’s a photographer for Magnum Photos, the most prestigious photographic agency in the world. He has covered extensively the conflicts in countries such as Afghanistan, Libya, Iraq, Syria, Sudan and Egypt, among others. He contributes regularly to The New York Times, The New Yorker and Time — among other giants — and has been recognized with several World Press Photo awards for his work.

Question. Many journalists dream of winning a Pulitzer Prize. You won two. How does that feel?

Answer. It’s obviously profound and moving for me, but also somewhat uncomfortable. I wish the value given to those images was given to the lives of the people I photographed, but the world doesn’t work that way. They’re the ones who have lived — and continue to live — with the consequences of war.

Q. You arrived in Syria two days after the fall of the Assad regime. What did you find?

A. An exhausted country. There was a mixture of resignation and a lot of dignity. People who have only known war — especially young people — find it hard to imagine the future, to imagine something they don’t know. The end of the dictatorship doesn’t mean happiness or freedom, but rather the beginning of another form of uncertainty: not knowing what happened to your children, your cousins, your mother, your father.

Q. What did it mean to return to Syria at that time?

A. I felt compelled to return. I covered Syria intermittently since the early days of the war. It was like coming full circle on a conflict that shaped my career, both professionally and personally.

Moises Saman, a Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist for the Magnum agency, in a courtesy photo.

Moises Saman, a Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist for the Magnum agency, in a courtesy photo.

Laura Boushnak

Q. In what way?

A. It changed the way I approach my work and understand the complexity of these conflicts. In war, the roles of victim and victimizer are constantly interchanged. And I wanted to convey that complexity visually. It meant rejecting objectivity and the idea of the journalist as someone trying to change what’s happening. That idealism was shattered.

Q. Your photos of Syria have a strong aesthetic component. How can one beautifully portray something so horrendous?

A. I always try to keep in mind that I’m photographing people; I don’t want to reduce them to the category of “victim.” I try to be more ambiguous visually. That opens other aesthetic doors; you can take other liberties, like this idea of photographing what’s not photographable — absence, what remains, pain — which was very important in the photos of Syria. This has forced me to look for different aesthetic solutions; I don’t know if it’s beauty.

Q. Is there an image from the series that has particularly impacted you?

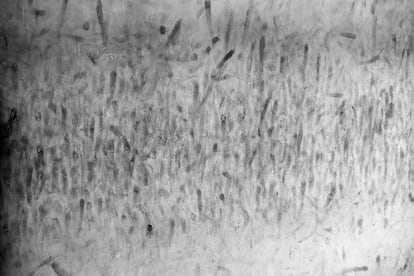

A. A very simple one, of a wall in a prison filled with faded fingerprints. The fingerprints of people who — upon being prosecuted — were made to mark their fingerprints [in ink]. Perhaps they then wiped their fingers on the wall. Each fingerprint represents a person with a story, with a family. We don’t know if they’re still alive, but that’s what’s left of them. That left its mark on me.

Fingerprints on a wall in the prison known as “Palestine Branch,” the last physical trace of detainees who disappeared under the Assad regime.Moises Saman (Magnum Photos)

Fingerprints on a wall in the prison known as “Palestine Branch,” the last physical trace of detainees who disappeared under the Assad regime.Moises Saman (Magnum Photos)

Q. There’s one photograph of a former prisoner on the floor of that same prison, recreating his torture, while his father looks on. How did that photo come about?

A. It was incredible. The boy’s name is Motasem Kattan; he’s in his twenties. We interviewed him at his home, two or three days after he left prison when the regime fell. He and his father insisted on taking us to the prison for the first time since he’d gotten out. I think that was his way of taking back control of his life: returning to that place, but in a completely different context than the one he’d been in just three days before. He showed the truth of what had happened to him. He wanted to touch the same walls, the same cell, so there would be no doubt that this had indeed happened to him.

Q. What makes a good photo?

A. A photo you can interact with. One where all the information isn’t there. One that forces you to look twice, where you find a personal connection, even if it’s about something you have nothing to do with. You have to feel something. It’s not so much about information, but about the heart — something visceral, even if you can’t quite define that connection in the moment.

Motasem Kattan recreates his captivity in the Syrian prison known as “Palestine Branch,” where he was detained and tortured for over a year.Moises Saman (Magnum Photos)

Motasem Kattan recreates his captivity in the Syrian prison known as “Palestine Branch,” where he was detained and tortured for over a year.Moises Saman (Magnum Photos)

Q. Jon Lee Anderson — your colleague in Syria and legendary journalist for The New Yorker — writes in the text accompanying your photos: “Along with the physical evidence of violence, there was a less obvious register of human loss — a phenomenon that Moises observes with singular sensitivity and skill.” Can you describe that register of human loss?

A. They’re elements that can humanize a situation that’s inhuman, or that has lost all humanity. Details that allow the viewer — someone who’s never been in these contexts — to connect with the person in the photo. With the photos we see every day from Gaza, for example: how many more photos can we continue to see of dead children — right in your face, the strongest photos — and we don’t react? There’s something there that we’ve lost, the power to react to something so inhuman, so unjust. So, we have to try to find other solutions. Perhaps taking a photo of the bedroom of one of these children — which they left behind before they died — perhaps this could have more of a connection with the viewer than seeing a photo of a lifeless child. I don’t know.

Q. What place should journalists occupy in conflicts like those in Syria or Gaza?

A. We have to preserve the dignity of the people going through these experiences. That’s something that’s been a guiding principle for me. Telling the stories with the complexity they possess, because they’re stories of people with names, biographies, dreams, memories and fears.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition