Case 1

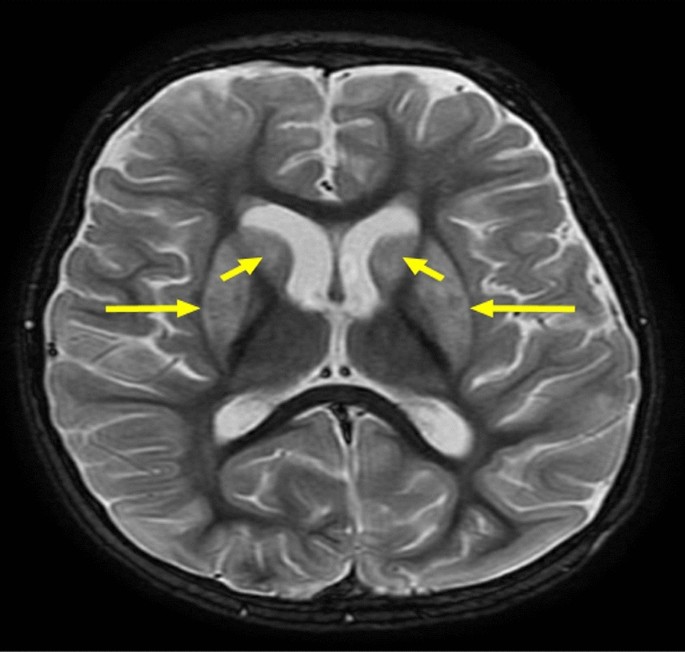

Case 1 involved a 6-year-old boy who was born full-term via normal vaginal delivery with a normal birth weight and no perinatal complications (Table 1). His mother had gestational diabetes mellitus that was treated with insulin; however, no history of neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission was noted. His health was unremarkable, and he was feeding well until the age of 6 months when he started developing abnormal movements characterized by tonic posturing of the upper limbs and uprolling of the eyes. Subsequent testing revealed hypoglycemia (2.4 mmol/L; normal range, 3.9–6.9 mmol/L) (Fig. 1) with elevated insulin levels (192 pmol/L; normal range, 12–150 pmol/L). Other laboratory findings were within normal limits. The patient was started on diazoxide therapy. During the safety fast test, he was able to fast for a few hours before developing hypoglycemia again (1.8 mmol/L), with insulin levels at 26.70 pmol/L and C-peptide insulin levels at 0.465 nmol/L (normal range, 0.26–0.62 nmol/L). Ammonia levels fluctuated between 147 and 157 µmol/L (normal range, 0–55 µmol/L) with negative urine ketones (Table 2). Metabolic screening and cortisol, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), and parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels returned normal, and he responded to the glucagon test within 30 minutes.

Table 1 Demographic data of the five cases and their management and complicationsFig. 1

The bar graph compares the initial and follow-up hypoglycemia levels (blood glucose in mmol/L) for each case. For case 2, we assumed an improvement to the normal range (3.9 mmol/L) as a demonstration, indicating no recurrent episodes after treatment. Case 5 is shown with placeholder values to illustrate potential improvement after pancreatectomy

Table 2 Initial investigations and gene mutations:

Both of his asymptomatic parents were nonconsanguineous, and none of his siblings were known to have hypoglycemia or pancreatic diseases. However, the patient had a family history of epilepsy on his maternal side. Developmentally, the boy has been meeting milestones appropriate for his age with no delays and dysmorphic features having been noted. He presented with hyperpigmented skin on the abdomen but no organomegaly; otherwise, his examination showed normal findings.

Management with diazoxide has been largely successful. However, the patient did experience a few seizure episodes in his life, with the first leading to his diagnosis and subsequent seizures occurring during periods of noncompliance with treatment or concurrent illness (Table 3). His mental and physical growth proceeded normally despite these obstacles.

Table 3 Long-term outcomes and hypoglycemia resolutionCase 2

Case 2 involved a 2-year-old girl who was the only child born to consanguineous parents and was delivered at term weighing 2.4 kg through normal vaginal delivery with no history of any perinatal complications or NICU admission. Examination revealed no family history of similar illnesses or pancreatic diseases (Table 1). Her medical history commenced at the age of 3 months when her mother witnessed episodes of tiredness, lethargy, and brief losses of consciousness lasting about 3 seconds, which initially occurred once or twice per week but escalated to three incidents in a single day. A critical sample taken during an episode, when her blood glucose level was at 2.1 mmol/L (normal range, 3.9–6.9 mmol/L) (Fig. 1), indicated elevated insulin and C-peptide levels, low ketones, and high ammonia levels at 117 µmol/L (normal range, 0–55 µmol/L) (Table 2). Following these findings, the patient was started on diazoxide and hydrochlorothiazide.

Further workup, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), revealed marked thinning of the corpus callosum and cystic changes in the basal ganglia, with no additional brain abnormalities. Clinically, although her weight was below the third percentile, her height was normal for her age at time of diagnosis. No developmental delays, dysmorphic features, organomegaly, or midline defects were observed, and her examination was otherwise normal. Genetic testing confirmed HI/HA syndrome due to a mutation in the GLUD1 gene and identified her as heterogeneous for a secondary gene PAH mutation class 2, which has been associated with recessive and early onset Mendelian diseases.

She was managed with diazoxide and hydrochlorothiazide, to which she responded effectively, with no recurrent hypoglycemia episodes having been reported since the last incident at the age of 3 months. Initially, she experienced multiple hypoglycemic attacks during 3 hours of fasting or when ill. A safety fast test revealed that the patient could now fast for up to 10 hours. Her physical and mental development continued normally without any neurological conditions (Table 3).

Case 3

Case 3 involved a 2-year-old girl with a history of frequent hospital admissions due to hypoglycemia and noncompliance with medication. Born via vaginal delivery after a pregnancy complicated by oligohydramnios, her perinatal history was otherwise unremarkable. Her parents were healthy, with no known consanguinity or family history of metabolic diseases (Table 1). At 35 days old, she exhibited an episode of abnormal movement characterized by stiffness of the hands that lasted for less than 5 minutes. Although no tonic–clonic seizures were observed, she was lethargic and difficult to arouse. Subsequent examination revealed low blood glucose (2.4 mmol/L; normal range, 3.9–6.9 mmol/L), high insulin levels (147.8 pmol/L; normal range, 12–150 pmol/L), elevated C-peptide (9.08 nmol/L; normal range, 0.26–0.62 nmol/L), and consistently high ammonia levels (214 µmol/L; normal range, 0–55 µmol/L), with negative urine ketones and low beta-hydroxylase levels (Table 2). Furthermore, blood gases and hormone levels were within normal ranges. Initial treatment included octreotide, later transitioning to diazoxide and hydrochlorothiazide. Echocardiography revealed mild left ventricular hypertrophy and pulmonary stenosis, while MRI showed significant brain abnormalities, including atrophic changes and ischemic signs.

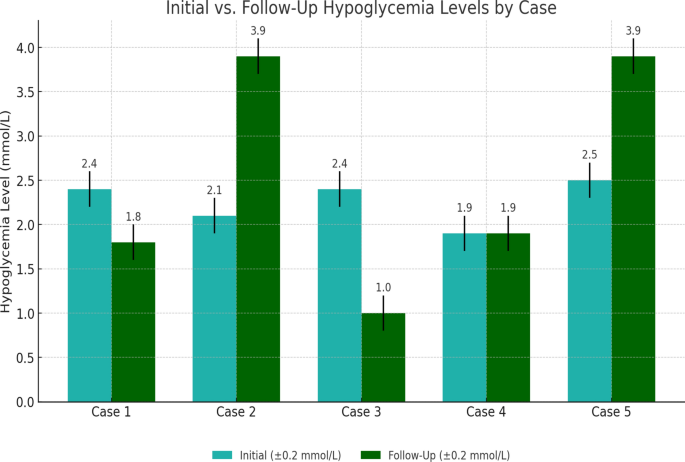

At 1 year old, she experienced a severe hypoglycemic event leading to a seizure and subsequent diagnosis of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, with electroencephalography (EEG) showing cerebral dysfunction and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) strongly indicating severe acute/subacute hypoglycemic encephalopathy (Fig. 2). Genetic testing confirmed HI/HA syndrome (GLUD1 gene mutation) and heterozygosity for secondary genes (ALDOB and SLC26A4 mutations class 1) associated with severe early onset Mendelian diseases. Currently, she is being treated with diazoxide and hydrochlorothiazide, which have effectively controlled her hypoglycemia and seizures. Clinically, her weight and height were below the third percentile for her age. Moreover, she showed significant developmental regression, currently presenting with global developmental delays, including loss of head control, inability to sit, spasticity predominantly in the lower limbs, and limited responsiveness to visual stimuli.

Axial T2-weighted brain MRI showing bilateral symmetrical hyperintense signal abnormalities (yellow arrows) involving the posterior limbs of the internal capsules and adjacent periventricular white matter. These findings may reflect demyelination, gliosis, or metabolic white matter involvement

Case 4

Case 4 involved a 5-year-old boy, born full-term with a birth weight of approximately 3 kg following an uneventful vaginal delivery and regular antenatal follow-up, who had no record of NICU admission. The boy’s health remained normal until the age of 6 months when his mother witnessed him convulsing without losing consciousness. These episodes recurred several times, prompting medical consultation. Initial investigations, including EEG, ecogradiograhpy, and comprehensive blood workup, returned normal results.

However, a safety fast test revealed low serum glucose levels at 1.9 mmol/L (normal range, 3.9–6.9 mmol/L). The critical samples showed low beta-hydroxylase levels and negative urine ketones, along with increased ammonia levels ranging from 137 to 109 µmol/L (normal range, 0–55 µmol/L), C-peptide levels of 0.651 nmol/L (normal range, 0.26–0.62 nmol/L), and an insulin level of 64 pmol/L (normal range, 12–150 pmol/L) (Table 2). Metabolic screening revealed no abnormalities, and hormone levels were within normal ranges.

He began to demonstrate abnormal movements after an illness at 22 months of age. These motions included drooling saliva and perioral cyanosis, along with generalized clonic movements and eye rolling. He went into a postictal state of sleepiness as the episode ended on its own. His blood glucose level was 1.9 mmol/L at this time (normal range, 3.9–6.9 mmol/L). The results of a subsequent EEG revealed normal findings. Hyperinsulinism nesidioblastosis (diffuse pancreatic uptake) was revealed on positron emission tomography (PET).

Although the patient had healthy siblings and no family history of endocrine disorders or similar illnesses, the patient’s parents are first-degree cousins. His weight and height were clinically below the third percentile. However, no midline deformities, dysmorphic characteristics, developmental delays, or organomegaly had been noted, with his evaluation largely revealing normal findings.

Diazoxide treatment has been effective, with the patient having no further seizure events or repeated hypoglycemia episodes for the past 2 years. His progress, both mentally and physically, has proceeded normally (Table 3).

Case 5

Case 5 involved a 39-year-old male who had been diagnosed with HI/HA syndrome secondary to nesidioblastosis following pancreatectomy at the age of 7 years for the management of pancreatic hyperplasia. The patient had a fasting insulin level of 47 pmol/L (normal range, 12–150) and a C-peptide value of 0.5 nmol/L (normal range, 0.26–0.62 nmol/L), which were particularly indicative of a history of recurrent hypoglycemia episodes (Table 2). His hypoglycemia, which was frequently uncontrollable, improved considerably after pancreatic surgery. Furthermore, the patient experienced recurring episodes of hypoglycemia-related increase in ammonia levels up to 300 µmol/L (normal range, 0–55 µmol/L) and the development of a seizure disorder as a secondary consequence. MRI revealed no anomalies. Genetic testing revealed a GLUD1 gene mutation in both the patient and his father.

The patient was managed through pancreatic enzymes, antiepileptic drugs, arginine and pyridoxine for hyperammonemia, and a specific diet. Regretfully, due to a genetic disorder, the patient has a severe intellectual handicap and static encephalopathy with lifelong neurological consequences, including cognitive impairment and a mix of spasticity and dystonia.