We make our slow way across the dying Atlantic, bound for a tiny volcanic island north of Sicily and southwest of the main Italian peninsula. Our vessel is the Solar Barque, a 59-foot vintage Hinckley sailing sloop owned by its captain, Ptolemy (“Tollie”) Quist, younger brother of my beloved mentor and friend, the expedition’s distinguished leader, Dr. Natalie Quist—to whom I’ll refer as “Dr. Q.”

Dr. Q: lean, petite, mid-fifties, close-cropped gray hair, big round glasses like a 1970s fashion designer. She wouldn’t have stood out in a high school teacher’s lounge or the check-out line of a discount supermarket to be honest, back when there were such things. First appearances can be deceptive, however. If you looked more closely you would see her as I do, as a figure of unusual luminosity and courage. Those blunt, pleasantly wrinkled, walnut-colored features. That strong chin angled out over the glittering swells, like a petite female version of George Washington peering off into the fog over the Delaware River. When she takes off her spectacles to clean the lenses on the hem of her hoodie you can really see the deep wrinkles radiating out from the corners of her twinkling eyes, a clue that she takes herself less seriously than George Washington ever did. Maybe Joan of Arc is a better analogy, though she would tease me relentlessly if I ever said that to her face.

UNDERWRITTEN BY

Each week, The Colorado Sun and Colorado Humanities & Center For The Book feature an excerpt from a Colorado book and an interview with the author. Explore the SunLit archives at coloradosun.com/sunlit.

Daughter of Cornelius Quist, famous tech wizard and billionaire of the twenties and thirties. Childhood spent rotating through various opulent dwellings around the globe, with private tutors, outback safaris, trips to Greenland and Antarctica to watch the dissolving ice caps. At the age of ten she went missing from her family’s TriBeCa apartment for three days; her panicked parents dispatched their aides and helpers, who eventually found her sitting in the front row of a conference room at Columbia, where she’d talked her way into a symposium on quantum computing. By the time she was twelve she’d solved a key problem in theoretical physics with an equation for calculating the values of dimensionless constants. Two years later she became one of the youngest students ever at MIT, and by the age of sixteen she’d coauthored a paradigm-shifting quantum field theory that resulted in her first Nobel Prize.

Dr. Q stayed on at MIT for a PhD in physics, focusing on the possibilities for real-world time dilation using insights from quantum mechanics and general relativity. After a stint at NASA she was recruited by the Centauri Project, a small, well-funded team of scientists and engineers created to lay the groundwork for a colonizing journey to an exoplanet orbiting the binary star of Alpha Centauri. A journey that never came to pass, of course; conditions on the home planet deteriorated far too quickly. But the underlying goal—saving our species from extinction—remains her animating passion.

But let me introduce you briefly to the other members of our four-person crew as well. Captain Tollie Quist, already mentioned, younger by three years than his famous sister and considerably less distinguished, sits at the wheel with his headphones on, his body convulsing almost imperceptibly to the repetitive beat of vintage electronica; James Swamp, our youngest crew member, flipping through obsolete bird guides in the shade of the forward bimini with his hoodie up as usual to conceal the severe scarring he received from his close brush with the hyperpandemic; and finally, yours truly, the team’s physician, Alejandra Morgan-Ochoa—though you’re free to call me Al, as everyone else does—leaning against the rail in my favored spot just aft the bowsprit, glancing up occasionally from this journal to make sure that absent-minded Dr. Q hasn’t somehow managed to fall overboard.

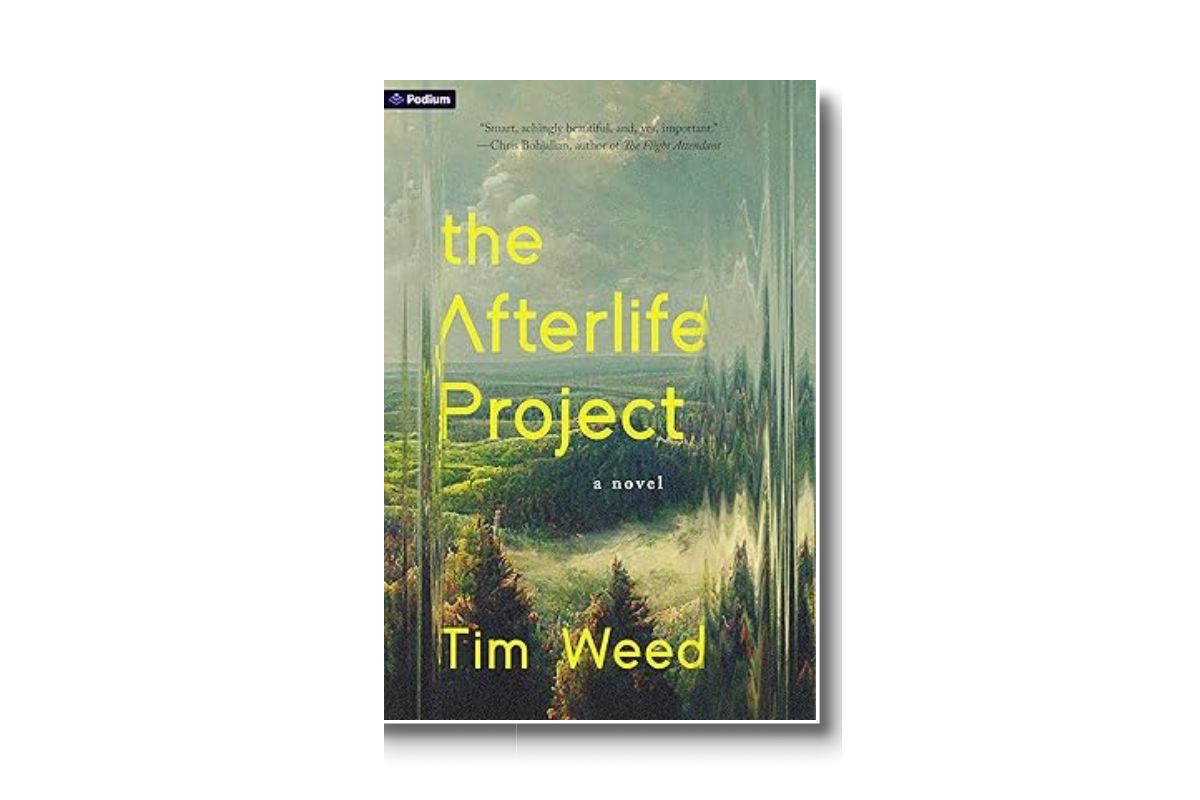

“The Afterlife Project”

>> READ AN INTERVIEW WITH THE AUTHOR

Where to find it:

SunLit present new excerpts from some of the best Colorado authors that not only spin engaging narratives but also illuminate who we are as a community. Read more.

The Quists’ vast inherited wealth meant more back in the days of banks and stock exchanges. All it means now is that we have the use of the Solar Barque and are well-supplied with food, water, and emergency fossil fuel. We do have some leftover technical equipment and a vintage Osprey mountaineering backpack half-loaded with minted gold bars. This helped smooth our way down the Connecticut River a few days after we boarded the yacht by allowing for the temporary removal of a barrier of floating oil barrels blocking our downstream passage. Gods know what use the well-armed river troll who operated that barrier is actually going to make of a dozen bars of solid gold in this day and age, but there’s no accounting for taste, and presumably he’ll find trading partners who share his fascination for that essentially useless yellow metal.

The truth is, for him and for us, there’s no escaping the grim reality of the present. The hyperpandemic was catastrophic on a scale beyond description and imagination. The number of dead will never be known, but it was the physiological changes that were discovered in the surviving population that truly rang the bells of doom for humanity across the planet. Because the microbe was an aerosolized component of the entire troposphere—the air itself—every single human being alive was exposed. Some developed immunities, yes, but even in the most asymptomatic survivors the pathogen had an invisible but irreparable effect. To be precise: surviving human females can no longer ovulate. Surviving human males can no longer generate active sperm. Which is why now, twelve years after the events we commemorate with a new calendar (A.U.C.T.) acknowledging the collapse of the international financial and telecommunications systems and the associated demise of Coordinated Universal Time, we live in a world completely devoid of children.

And we thus find ourselves contemplating a singular probability that has never been experienced since the dawn of our species on the African savannah approximately 300,000 years ago. Unless a solution can be found, Homo sapiens will cease to exist.

Unless, that is, the rumors that moved us to embark on this voyage happen to be true.

🎧 Listen here!

Go deeper into this story in this episode of The Daily Sun-Up podcast.

Subscribe: Apple | Spotify | RSS

These rumors, which are really little more than intriguing hearsay in this vast post-telecommunications world, concern a few small, remote, volcanic archipelagos thought to harbor populations with some degree of persistent fertility. That the islands are volcanic is significant: in theory, humans exposed over many generations to the aerosolized ejecta of regularly occurring geothermal eruptions—gas, steam, ash—may possess special genetic immunities to the devastating microbes that were mixed into every cubic millimeter of our lower troposphere twelve years ago. Microbes thought to have originated in geothermally heated groundwater were broadcast far and wide by the series of massive, intentionally triggered volcanic eruptions popularly known as the Pinatubo Solution. (More on this infamous colossal boondoggle later, perhaps. Trust me, you don’t want me to go into it now.)

One of these anomalous archipelagos is thought to be the Juan Fernández Islands off the Pacific coast of South America, but getting there now that the Panama Canal is closed would have required us to either sail all the way around Cape Horn and back, or to set off across the North American continent by land, with the uncertain goal of trying to beg or steal a seaworthy boat in what used to be California or Mexico, and returning. Crossing the Atlantic and part of the Mediterranean, as it happens, is a far easier lift, which is why the second anomalous archipelago—the Aeolian chain near Sicily, and specifically the small island of Stromboli—is our chosen destination. When we arrive, our goal will be to locate between one and three fertile females and to bring them back with us across the ocean to the Centauri Project Lab, which is located in the northwestern region of what used to be the state of New Hampshire.

Now the time has come for me to enjoy a few hours’ sleep before our captain passes by my berth, ringing his accursed vintage cowbell to wake me in time for my four-hour watch. My plan is to be as diligent as possible with these entries from now on. To recount everything exactly as it unfolds, with the hope that by the time you finish reading these pages you will be in possession of the complete story of our unlikely quest. If we succeed, it will be a story for the ages. If we fail, then you, dear reader, are likely nothing but the fleeting construct of one long-dead woman’s overly optimistic imagination.

Excerpted from “The Afterlife Project” by Tim Weed

Copyright © 2025 Podium Publishing LLC. Reprinted with permission.

Tim Weed is the author of “The Afterlife Project” and two previous books of fiction. He is the recipient of the Tobias Wolff Award for Fiction, the Montana Prize, the Fish International Short Story Award, and multiple Writer’s Digest Fiction Awards. He serves on the core faculty of the Newport MFA in Creative Writing and is the co-founder of the Cuba Writers Program. A former expert for National Geographic Expeditions, Tim spent the first part of his career directing international educational programs in Spain, Portugal, Australia, and Iceland. Tim grew up in Denver and Littleton, Colorado.

Type of Story: Review

An assessment or critique of a service, product, or creative endeavor such as art, literature or a performance.