Medics say more nuanced policy needed with greater regulatory distinction between harmful PFAS and essential fluoropolymers used in medical devices

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), often referred to as ‘forever chemicals’, are frequently treated as a single class by the media, legislators and the public. However, articles recently published in Heart Rhythm – the official journal of the Heart Rhythm Society, the Cardiac Electrophysiology Society, and the Pediatric & Congenital Electrophysiology Society – have emphasised the need to distinguish between hazardous PFAS and fluoropolymers, which are widely used in healthcare and have not been shown to pose the same risks to human or environmental health.

PFAS comprise more than 12,000 compounds used across a broad range of industries including textiles, aerospace, electronics, pharmaceuticals, and healthcare. Due to their chemical stability, certain small-molecule PFAS – such as perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) – have been linked to water contamination and adverse health outcomes. These two substances are classified as environmental contaminants by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

In contrast, fluoropolymers – a specific subset of PFAS – are large, inert compounds that are not considered environmental contaminants by the EPA and have undergone extensive testing for biocompatibility.

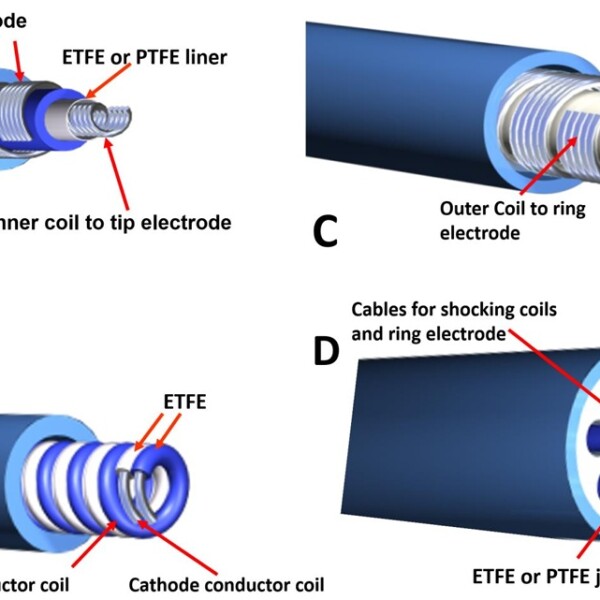

According to the US Food and Drug Administration, approximately 250,000 approved medical devices contain fluoropolymers. These include cardiac implantable electronic devices, ablation catheters, and vascular grafts. Their unique combination of lubricity, flexibility, temperature resistance and electrical insulation makes them vital in manufacturing, performance and the safe delivery of modern medical devices.

Writing in Heart Rhythm, clinician Dr Pierce J. Vatterott, of the Minneapolis Heart Institute, Minnesota, together with biomaterials scientists Dr Paul D. Drumheller, Dr Nadine Ding and Dr Joyce Wong explained that no other class of materials replicates the essential performance characteristics of fluoropolymers. The authors noted that fluoropolymers have been used safely for more than five decades in devices such as catheters, pacemakers, defibrillators, cardiac valves and brain shunts.

In a related commentary, Dr Roger Carrillo, chief of surgical electrophysiology at Palmetto General Hospital, Florida, highlighted the clinical importance of fluoropolymers:

“These compounds have enabled key advances in cardiac technologies, including miniaturisation of devices and improved insulation. Unlike the small PFAS molecules linked to health risks, fluoropolymers have not been associated with environmental or clinical harm,” he said.

A second article in the same issue examined the potential impact of legislative developments on the availability of fluoropolymers. Lead author Dr Drumheller, from the American Institute for Medical and Biological Engineering in Washington DC, warned that many legislative efforts in the United States, Canada and the European Union propose regulating PFAS as a single class.

This includes fluoropolymers, despite their distinct properties and proven medical value. Although some exemptions exist for medical devices, regulatory uncertainty is already affecting supply chains, as manufacturers pre-emptively exit the market.

An editorial by Professors Kenneth A. Ellenbogen, of the Medical College of Virginia / VCU School of Medicine, Richmond, Virginia, and Charles D. Swerdlow, of the Smidt Heart Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, California has expressed concern that conflating toxic small-molecule PFAS with fluoropolymers risks disrupting clinical practice. They noted that the ongoing regulatory uncertainty could jeopardise the future availability of many medical technologies.

Dr Vatterott concluded that without a clearer regulatory distinction, the withdrawal of fluoropolymers from the market could have serious consequences for patient care.

“It is essential to strike a balance between protecting the environment and ensuring continued access to materials that are critical for safe, effective and minimally invasive medical procedures,” he said.

The call comes in response to The American Chemical Society (ACS) statement earlier in the year which defended the current OECD definition of PFAS as scientifically sound and essential for effective monitoring. The OECD classifies PFAS based solely on molecular structure – specifically, substances containing at least one fully fluorinated methyl or methylene group.

This approach captures a wide range of persistent chemicals, including lesser-known precursors and degradation products such as trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) – and includes fluoropolymers – which underpins many environmental monitoring and compliance methods.

The ACS warns that efforts to revise the definition, including those led by IUPAC – the international authority on chemical nomenclature – risk undermining public health protections and regulatory coherence. Industry groups have lobbied for a narrower definition that would exclude commercially and medically valuable substances such as fluorinated gases, fluoropolymers and certain pharmaceuticals.

Scientists from the ACS stress that while exemptions for specific uses may be warranted, these decisions should be made transparently within regulatory frameworks, not by weakening the foundational chemical definition. Narrowing the scope could disrupt laboratory methods, exclude important PFAS precursors from oversight and lead to inconsistent policies across jurisdictions.

The statement concludes with a call to retain the OECD’s structure-based definition as the global standard, warning that any move away from it would compromise the integrity and effectiveness of PFAS regulation.

For further reading please visit: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2025.05.057

Other related articles:

“The role of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in medical devices and delivery systems: Why the electrophysiologist should care,” by Pierce J. Vatterott, MD, FACC, Paul D. Drumheller, PhD, Nadine Ding, PhD, and Joyce Y. Wong, PhD (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2025.05.057). It is openly available for 60 days as of July 14 at https://www.heartrhythmjournal.com/article/S1547-5271(25)02518-4/fulltext.

“PFAS regulations and the potential impacts on patient care,” by Paul D. Drumheller, PhD, Nadine Ding, PhD, Joyce Y. Wong, PhD, Dawn Beraud, PhD, and Pierce J. Vatterott, MD, FACC, (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2025.05.058). It is openly available for 60 days as of July 14 at https://www.heartrhythmjournal.com/article/S1547-5271(25)02519-6/fulltext.