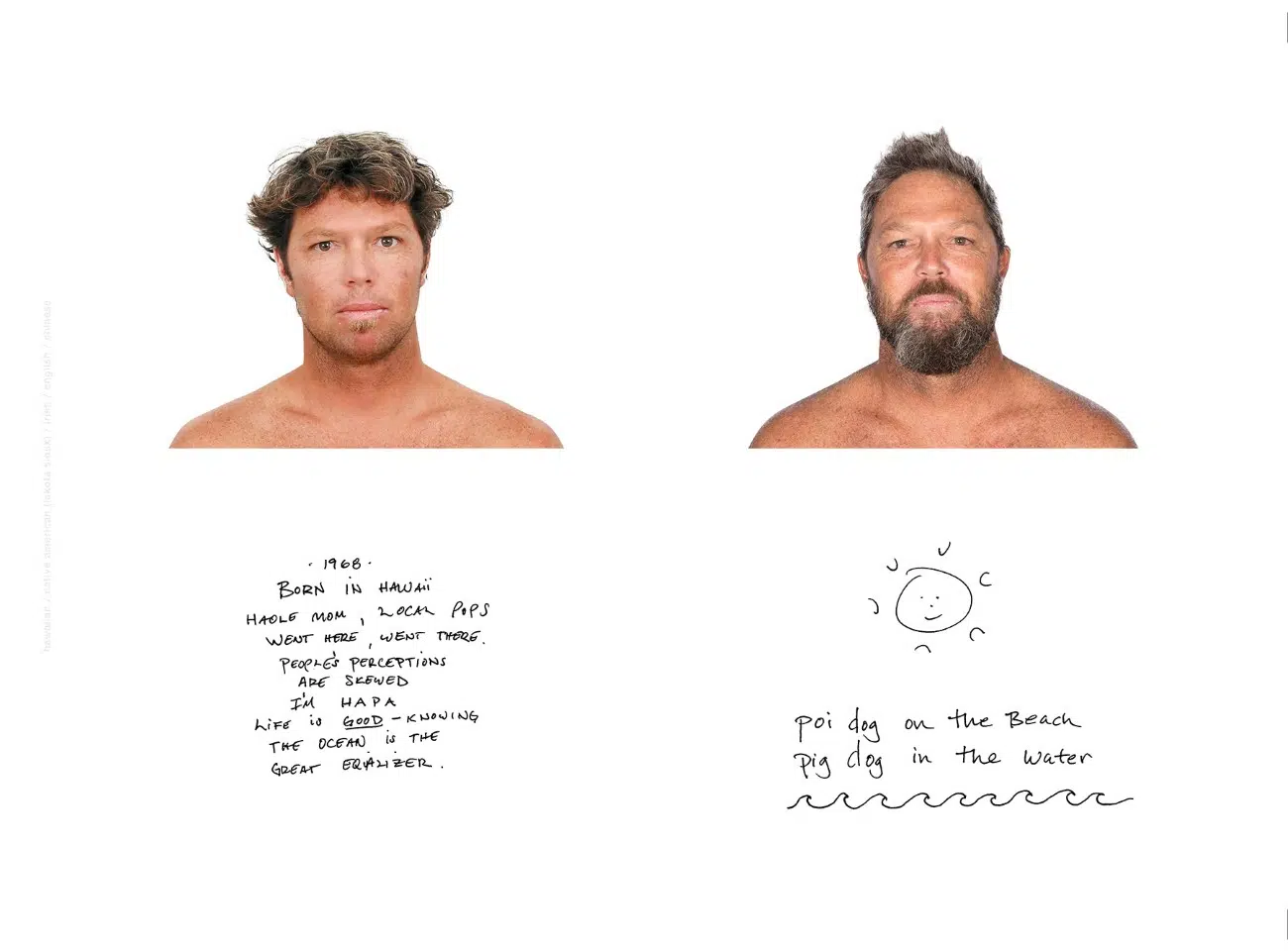

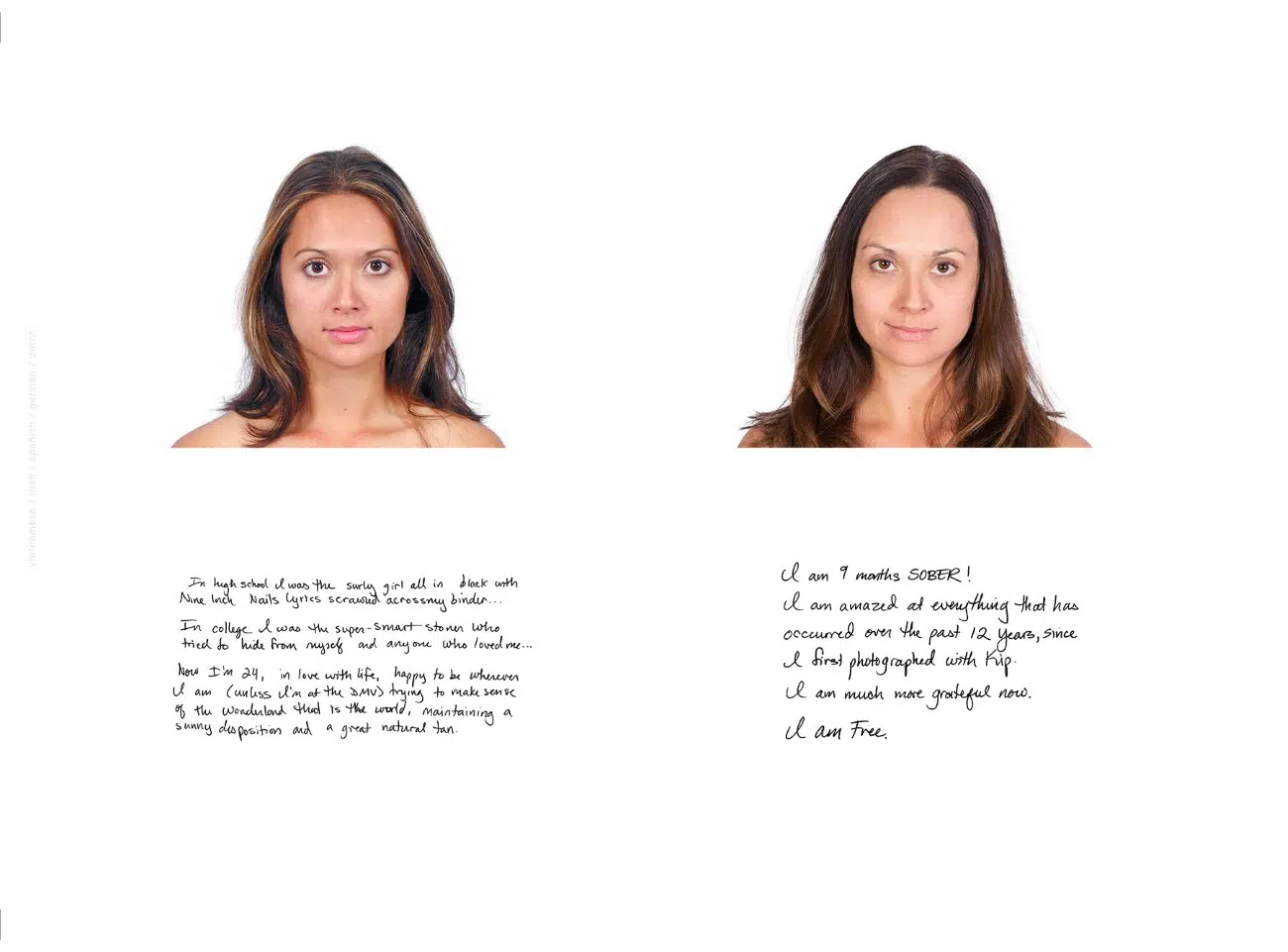

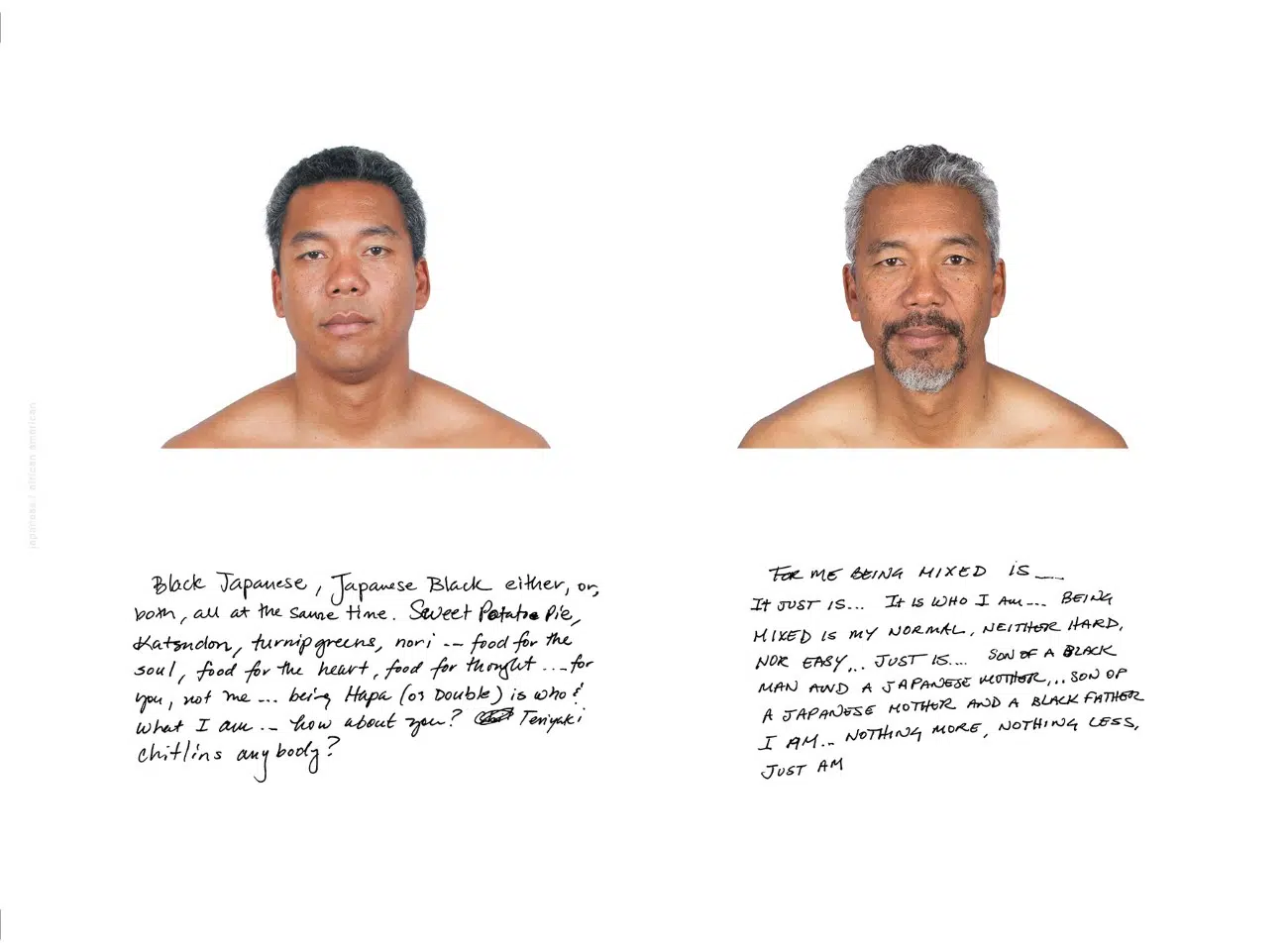

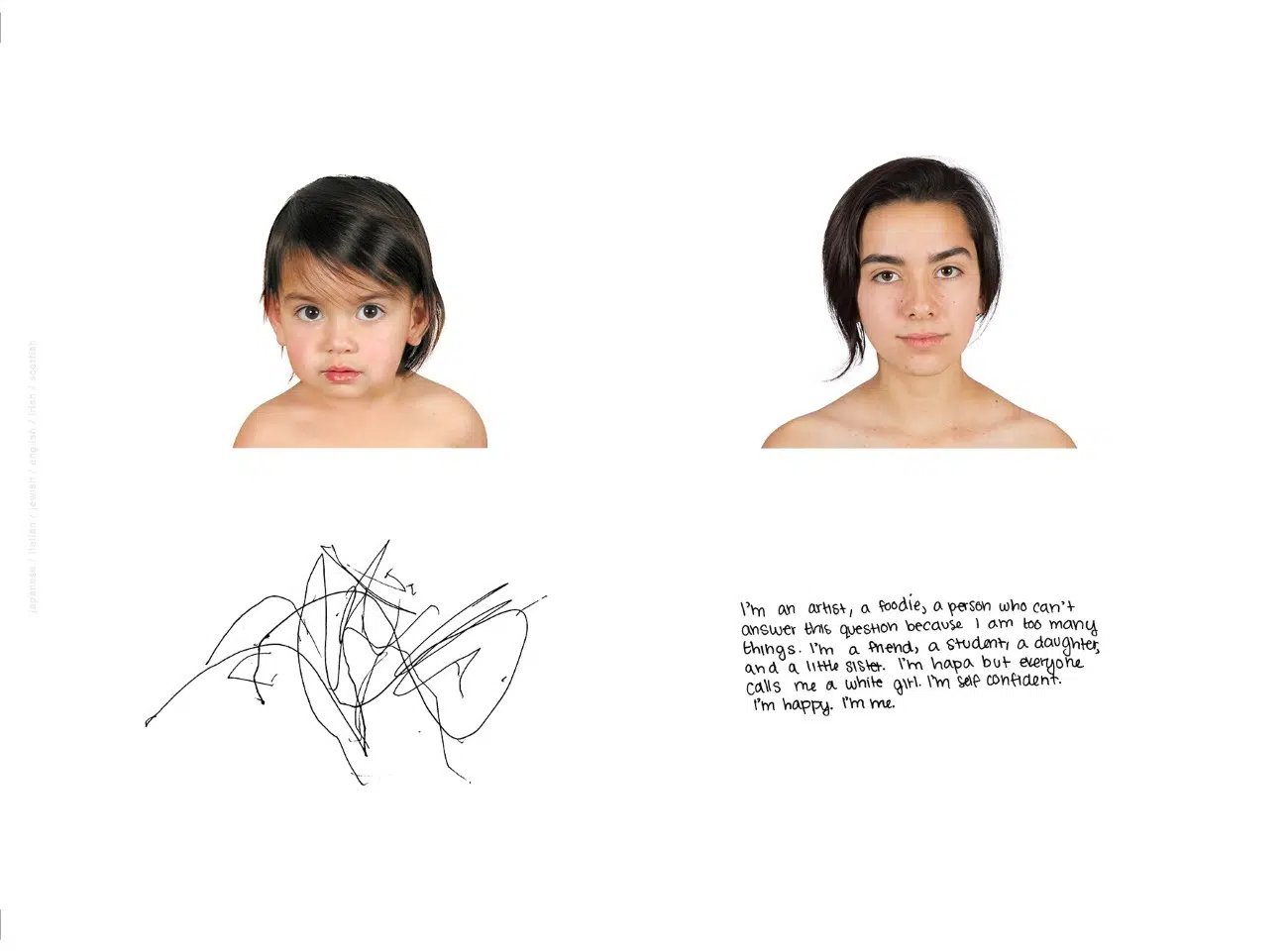

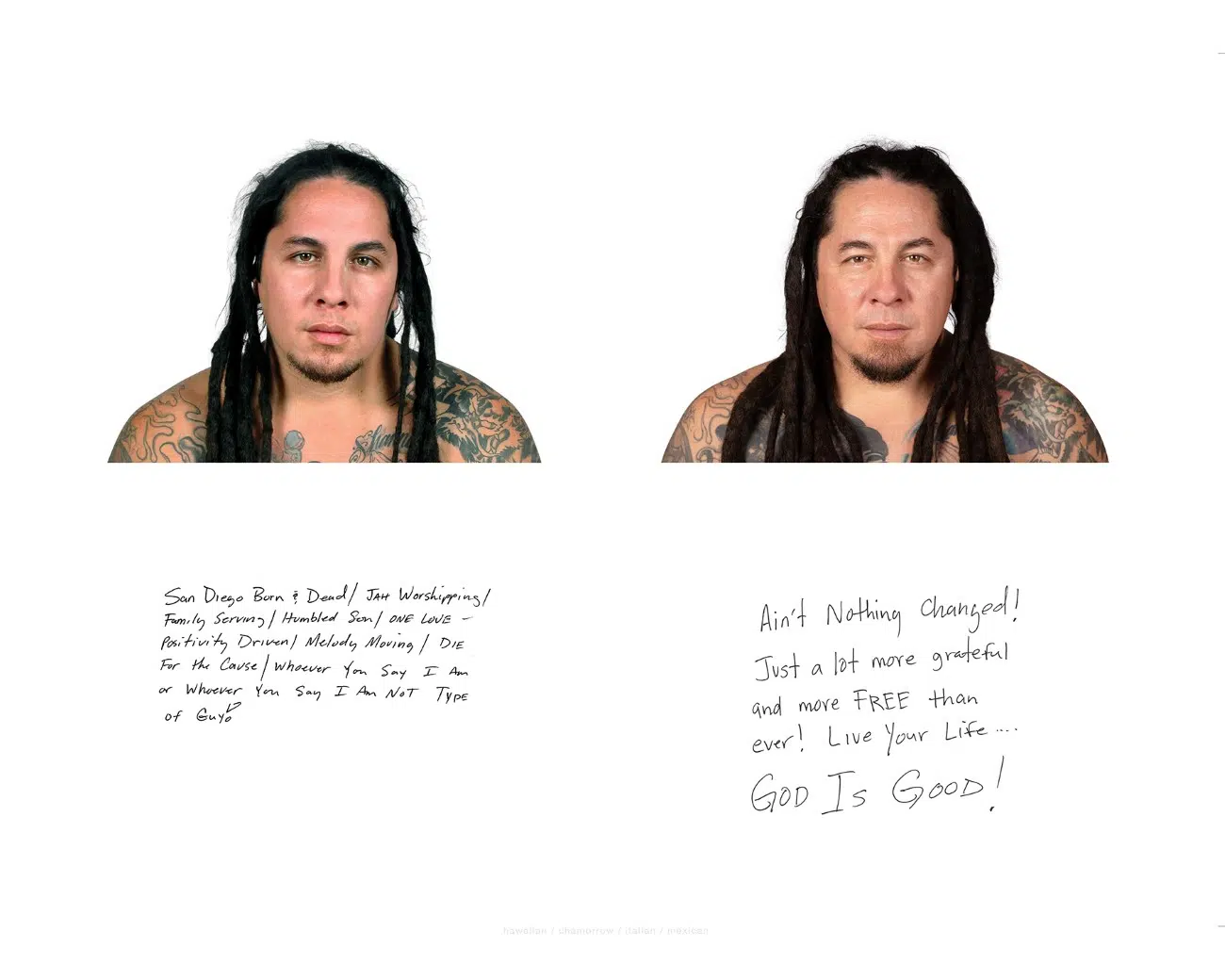

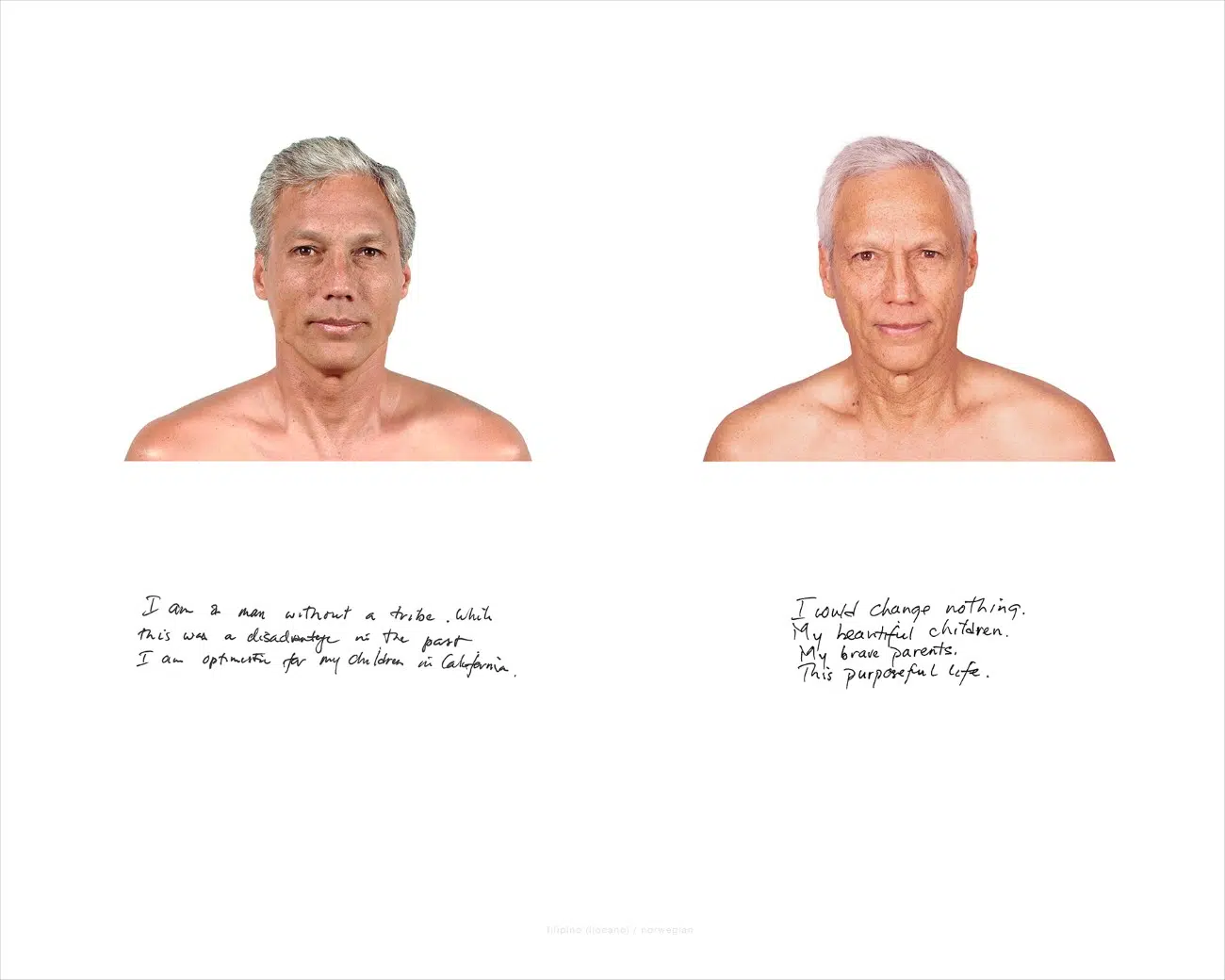

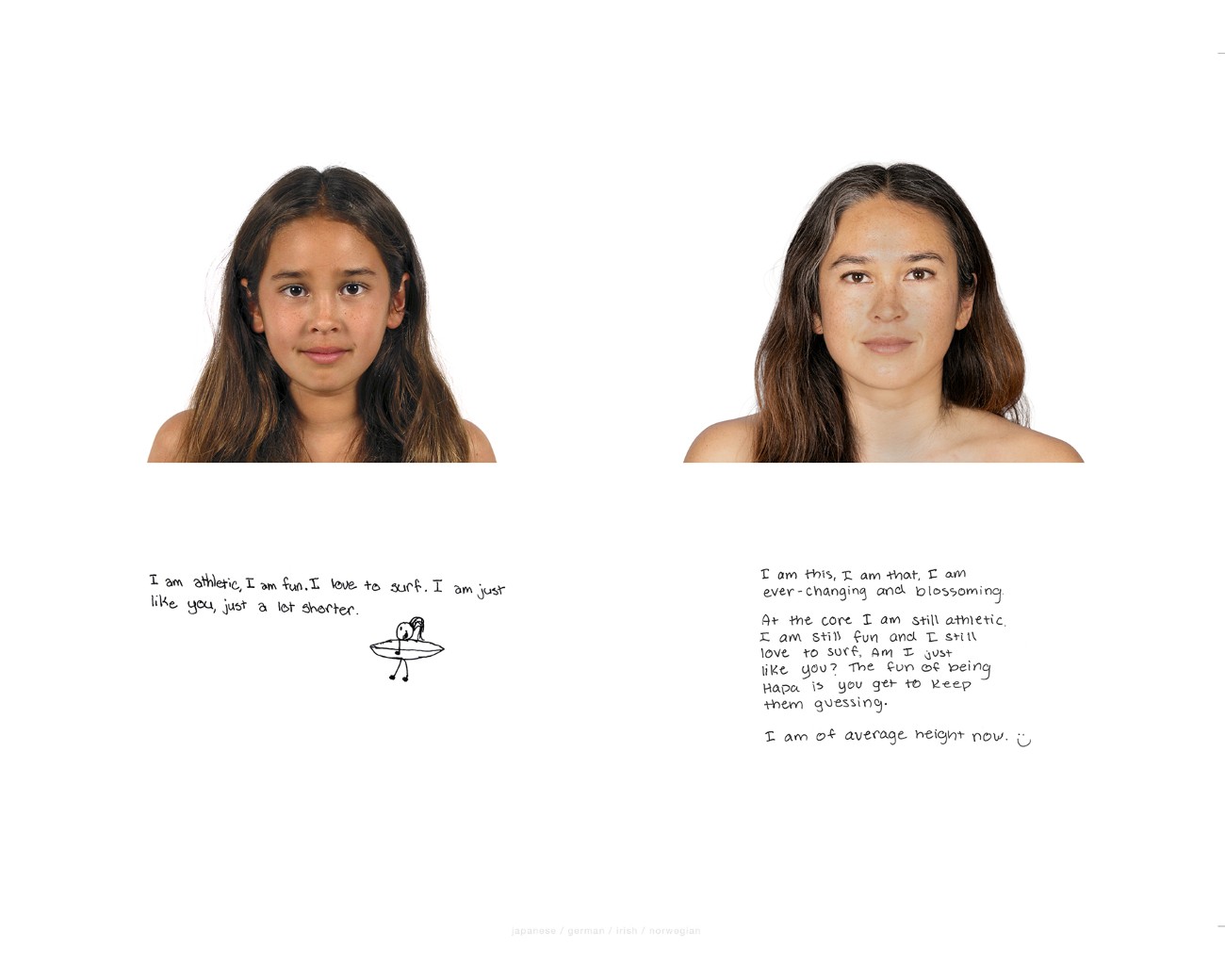

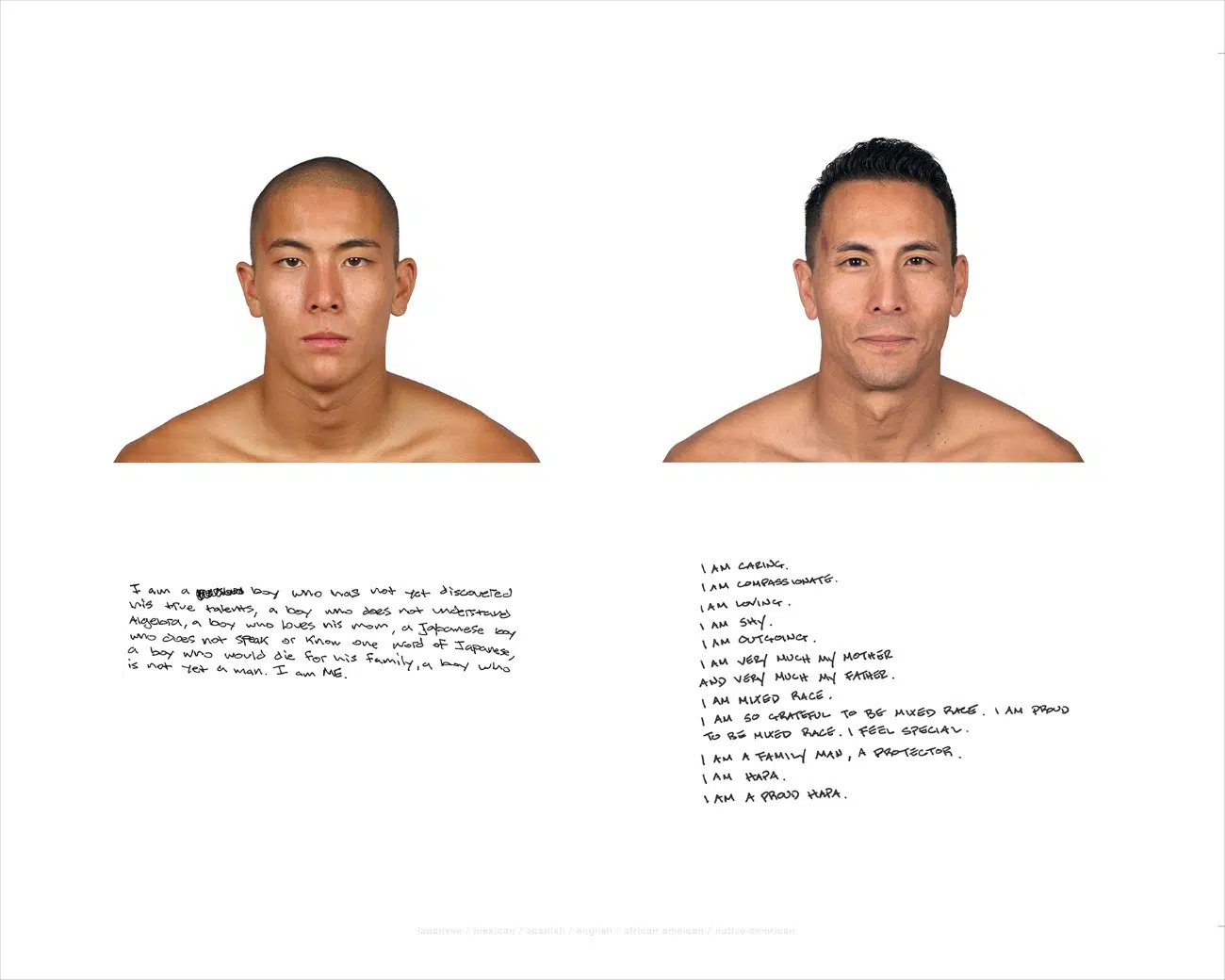

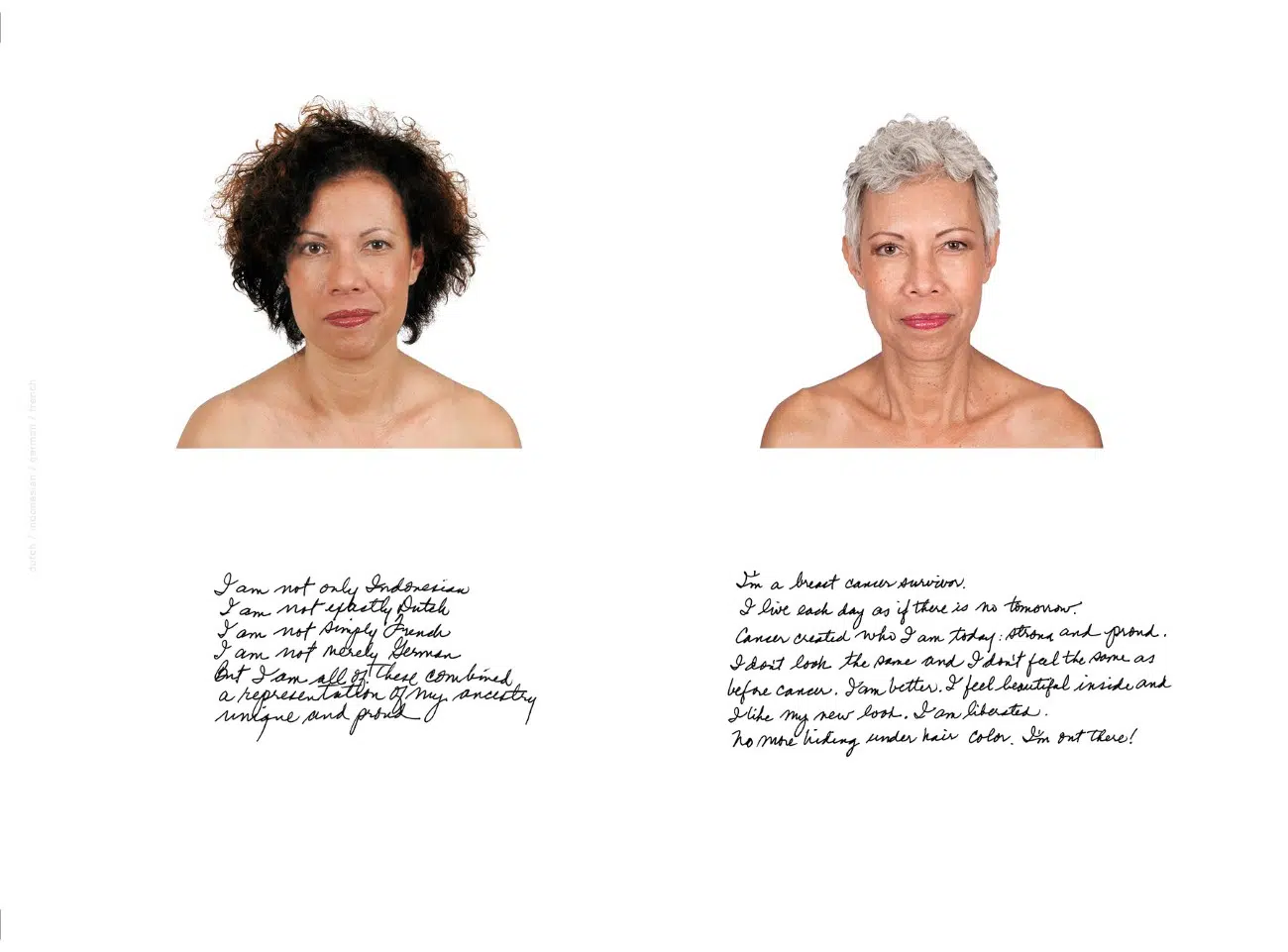

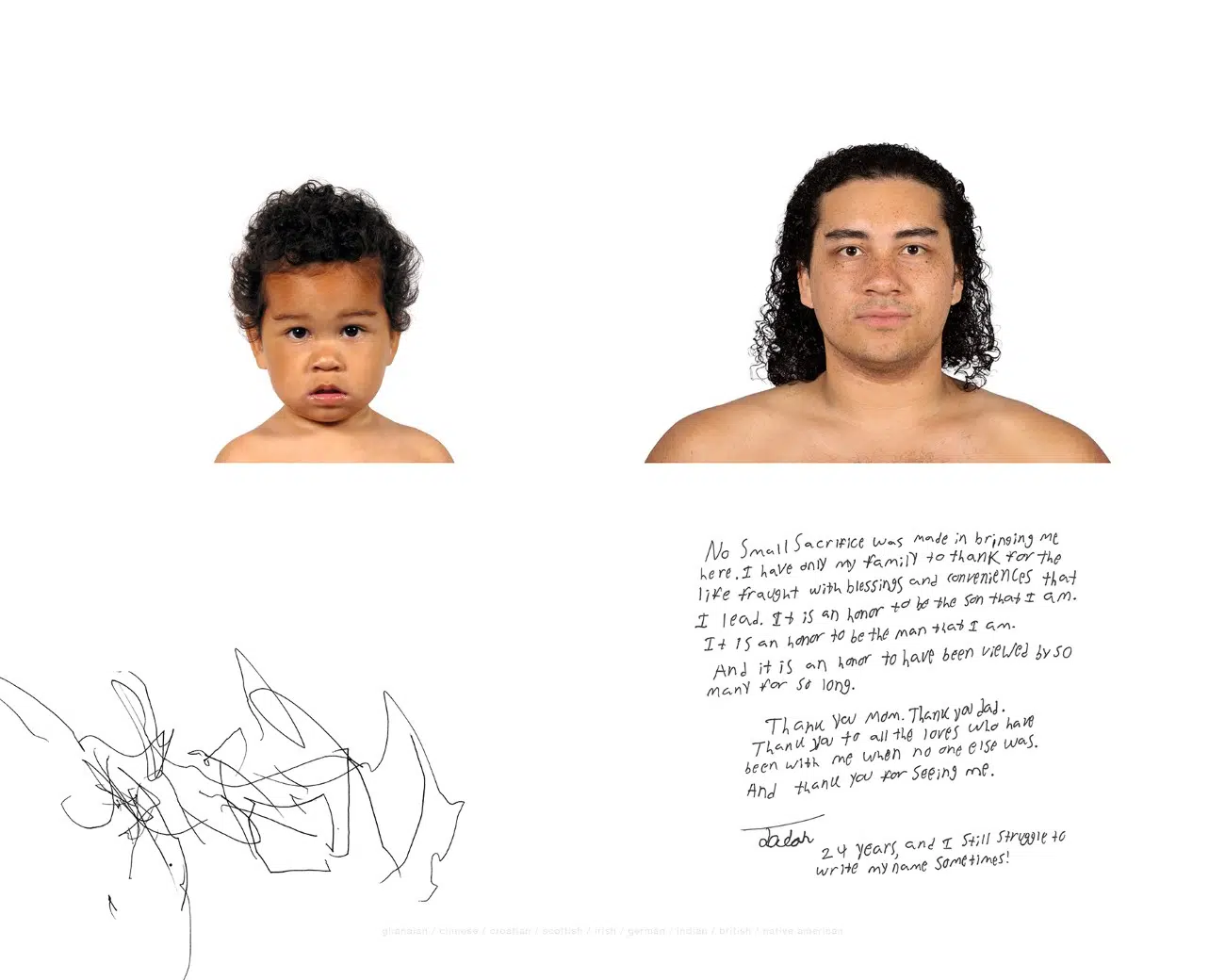

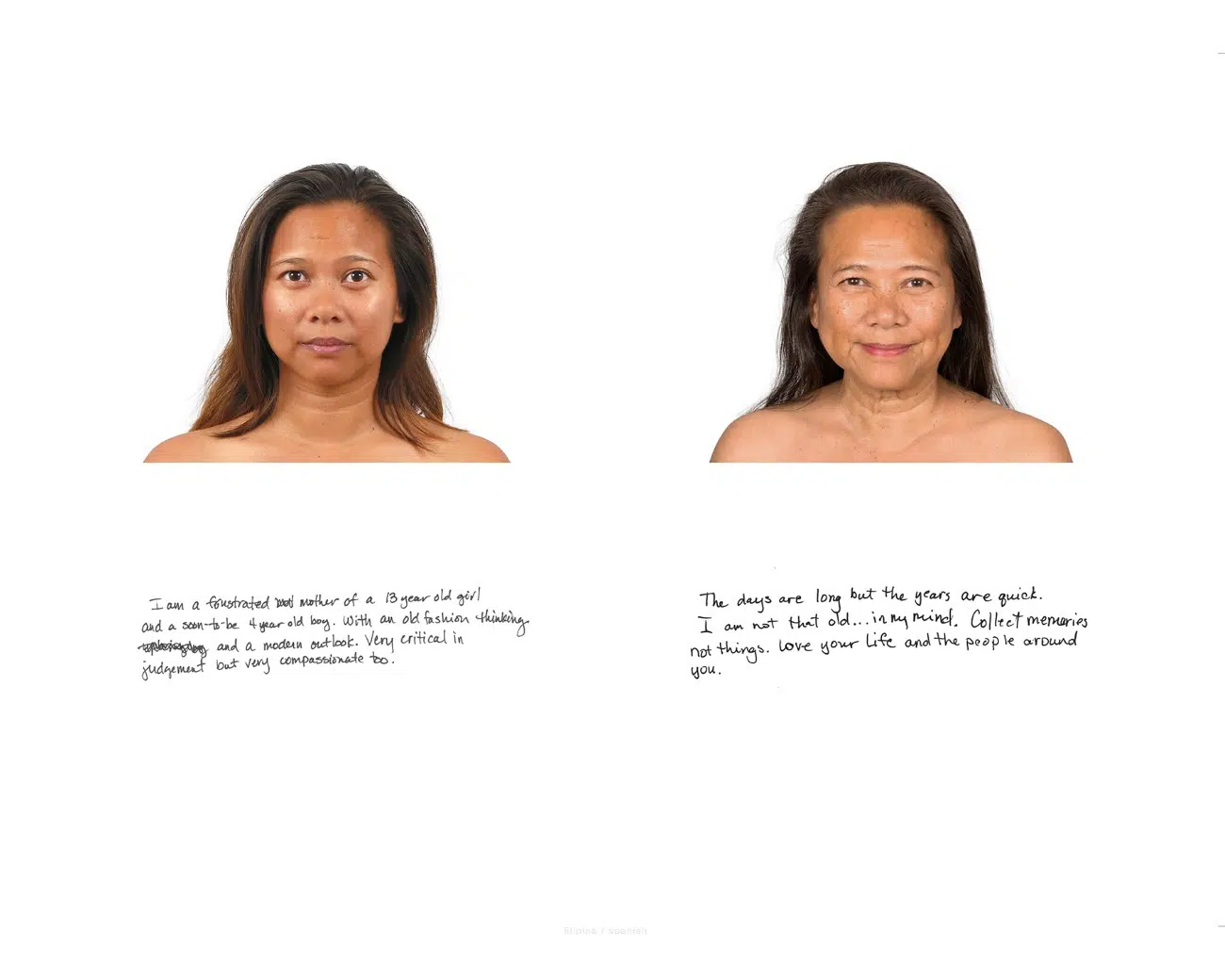

Artist and photographer Kip Fulbeck is revisiting his examination of identity as someone of mixed Asian descent. In 2000, he set out to create The Hapa Project, photographing people, like himself, of mixed heritage. Now, 25 years later, he has returned to photograph 130 of the original participants and to add to The Hapa Project in an effort called hapa.me.

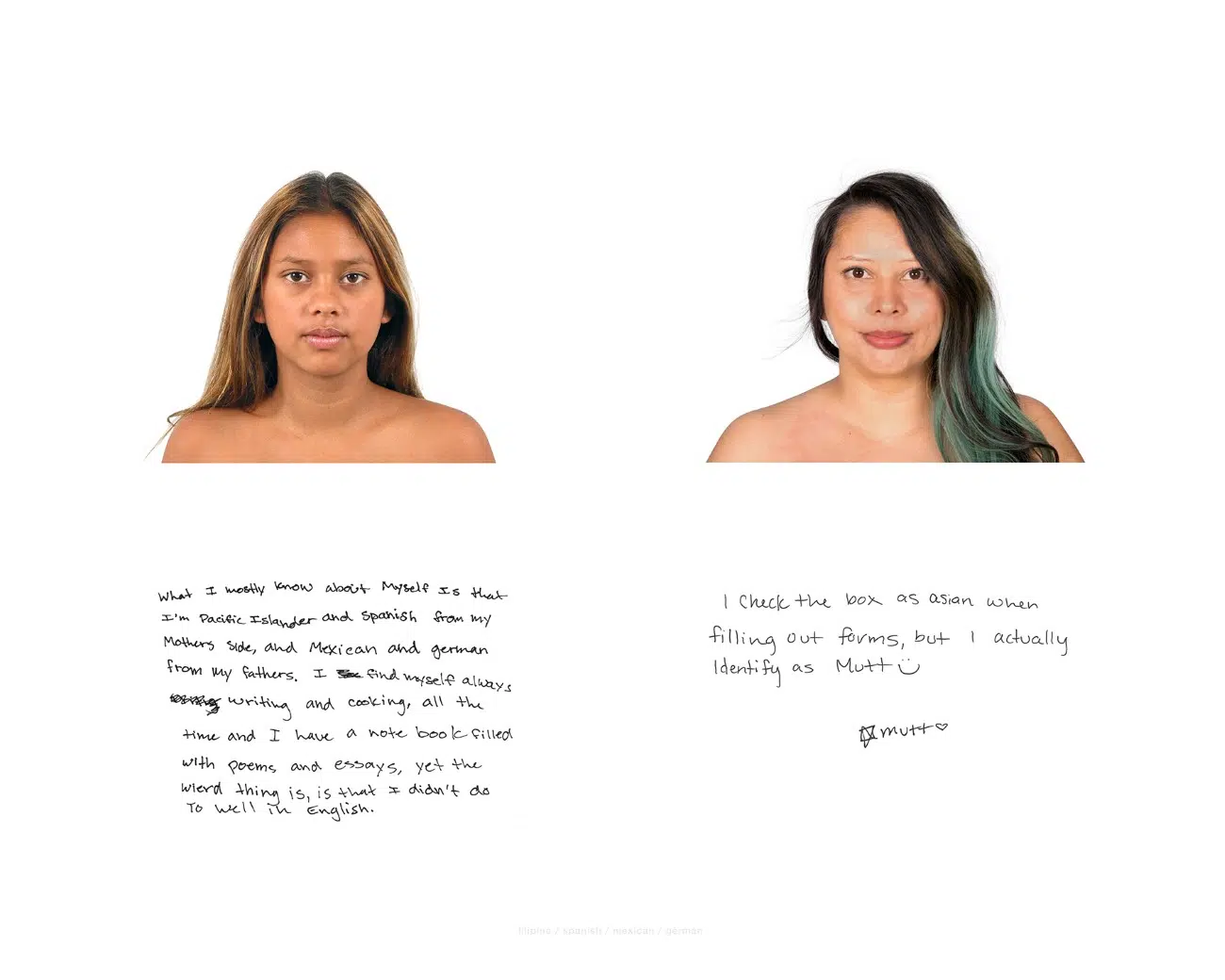

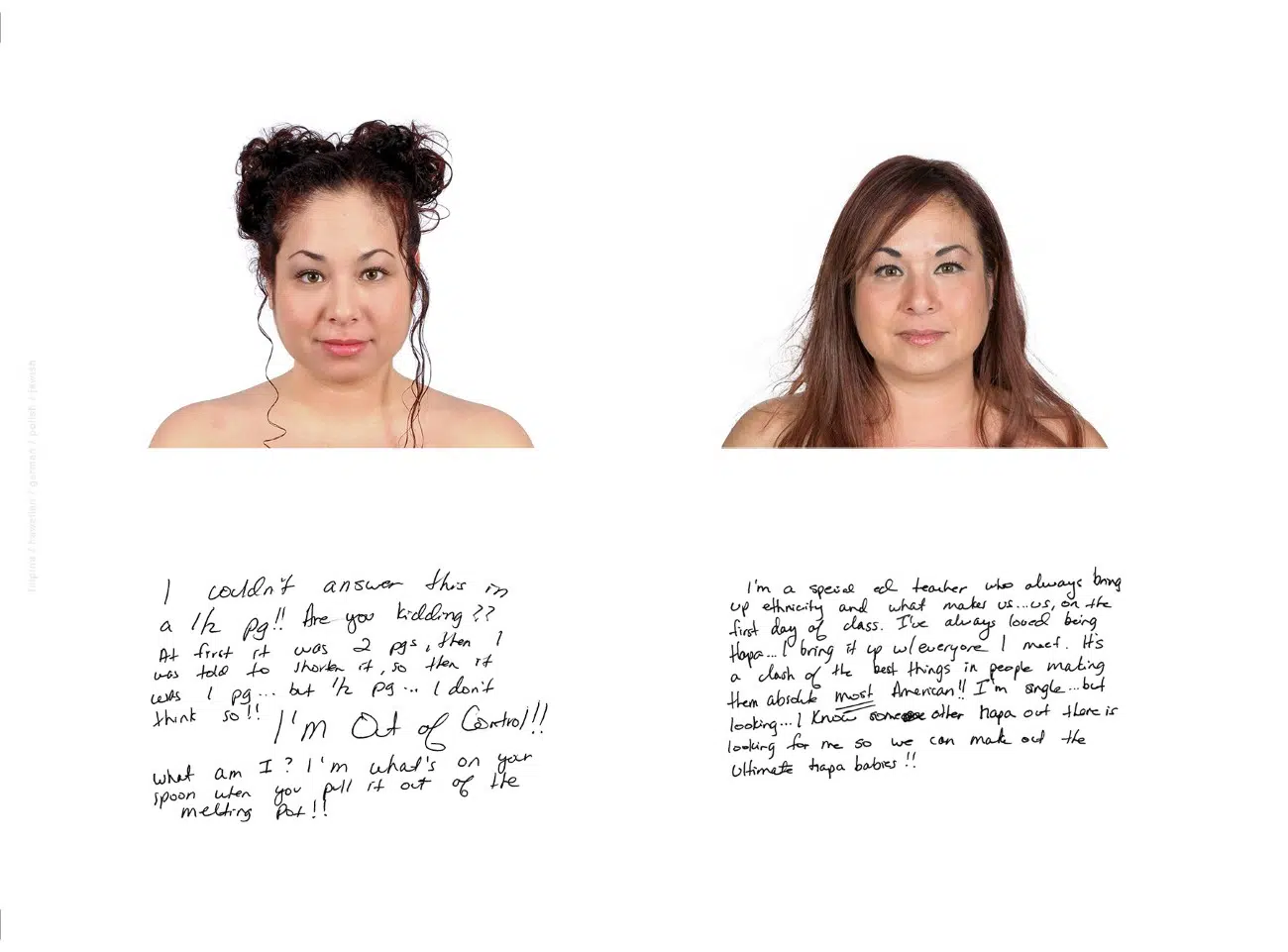

The word “hapa,” meaning “half” in Hawaiian, is the starting point of this reflection on identity and self. This word, which was first used to describe those of mixed Hawaiian and European descent, has not been enlarged to encompass anyone with mixed heritage. Fulbeck has used the word as a starting point for discourse, taking the portraits of participants and then asking them to write their response to a seemingly simple question—“What are you?”

Now, more than ever, Fulbeck’s project has taken on new meaning. In an era in which American attitudes toward race are rapidly evolving, these reflections are more important than ever. The new evolution of the project is currently on display at San Diego’s Museum of Us through summer 2027, allowing the public to interact with the work and, on select dates, have their own portraits taken for inclusion in the exhibition.

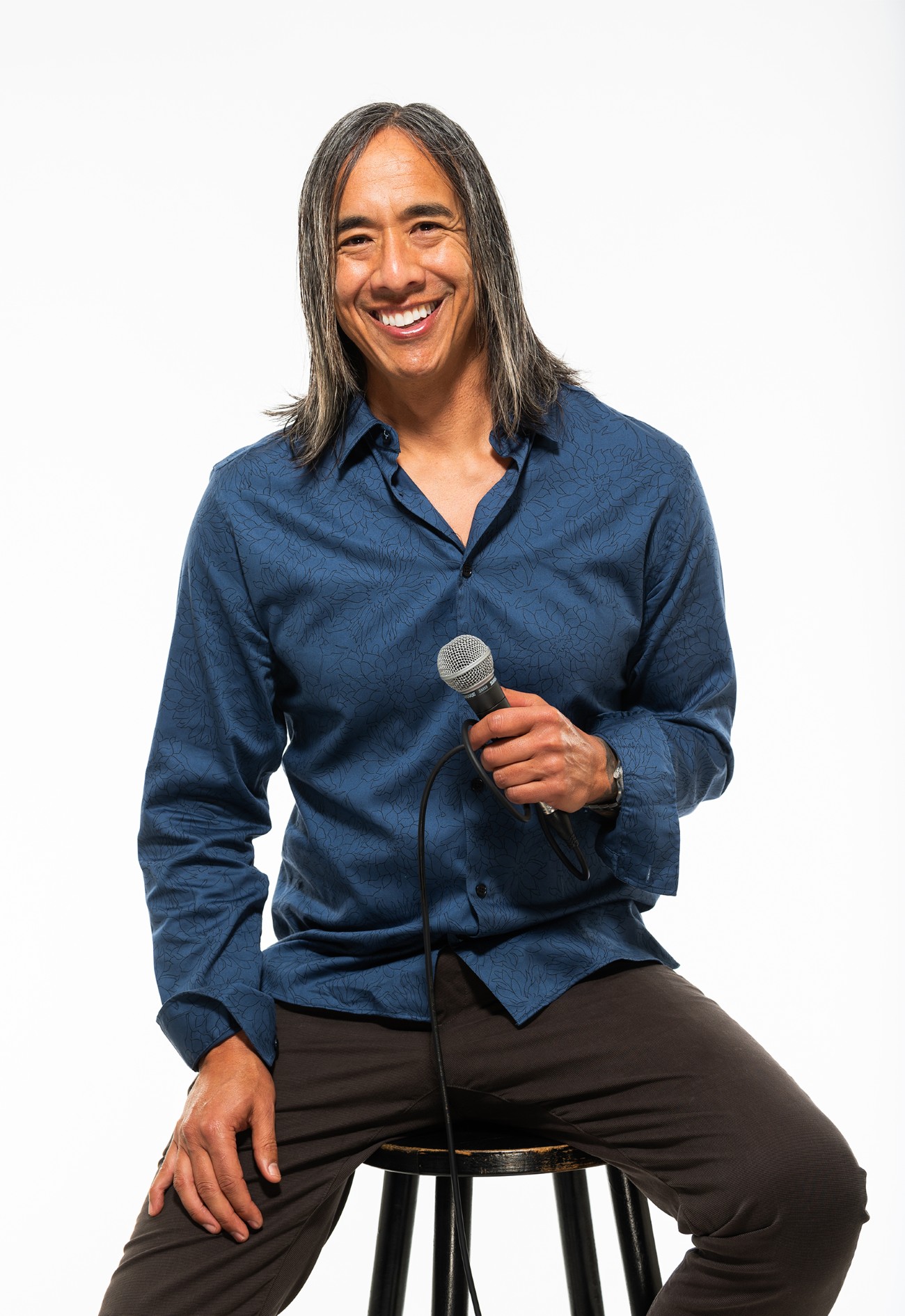

We had the opportunity to speak with Fulbeck about The Hapa Project, its initial inspiration, and how it—and he—has evolved over the past 25 years. Read on for My Modern Met’s fascinating interview with the photographer.

What does the word “hapa” mean to you?

I first heard the word “hapa” as a child in the early 70s, when one of my cousins told me that’s what I was. This was in Monterey Park, a predominantly API city in LA County often referred to as the First Suburban Chinatown. My mother had immigrated here from Taiwan with five children (My siblings are all full-blooded Chinese, as are my cousins. I was the only mixed kid in my extended family). She met my father at USC, and when they married, anti-miscegenation laws were still common throughout the country. To think of their marriage and my subsequent birth as somehow illegal is bizarre by today’s standards, and rightfully so.

Etymologically, “hapa” is the Hawaiian transliteration of the English word “half.” Much of its current usage derives from the phrase “hapa haole,” meaning “half White” or “half foreigner.” The phrase was originally coined by Native Hawaiians to describe people of mixed ethnicities resulting from encounters between islanders and white settlers. As migration increased between the islands and the mainland, the word was re-borrowed back into conventional English, gaining particular popularity on the West Coast.

Kip Fulbeck

How did you find the participants?

For the original shoots, they mostly found me. I’d announce a session, and people would just turn up. In places like LA, San Francisco, or New York, I’d often arrive early for set up and find people already waiting outside. I realized I was onto something—that people really wanted to be recognized for who they are, that they were tired of being put into others’ boxes, and that there was importance in finding others who shared similar experiences. I also shot in Boise, Chicago, Honolulu, Madison, San Diego, San Jose, Seattle, and Waimanalo. Every city was different. Not just in terms of numbers, but often also in their attitudes and the topics they chose to write about.

When I rephotographed people 20 years later, I wanted to open it up to new participants as well. But I wasn’t prepared for such an overwhelming response. My first shoot in LA filled every appointment 30 minutes after announcing. I scheduled a second one, and the same thing happened. I ended up doing eight shoots in LA alone and could have done more. One person even told me, “I’ve been waiting 15 years to be part of this.” This was really meaningful to me personally, as prior to this, I really had no way of understanding the work’s impact.

What has most surprised you about answers you’ve seen to “What are you?”

Two things. The first is how brilliant people are when given the opportunity to tell their story. I am constantly amazed at what people come up with—their humor, their poignancy, but most of all, their honesty. The second is how difficult it can be for some individuals to answer the question. I had one woman stay over two hours with pen in hand but never writing a thing. I encouraged her to just start the process, to try writing a bit and throw it away and start over, to cross things out, but she just shook her head. At the end of the session, I told her I was sorry but had to leave, and she tearily said, “I can’t do this,” and walked off. Sometimes the simplest question or the simplest task can be so powerful.

What made you decide to revisit the project 25 years later?

The easy answer is that people asked for it. I’d often field questions about a possible update or sequel, about ways to expand the project. People wanted to participate. Looking at it now, though, I understand it’s more than that. This project was a gift to me as an artist. I was given a platform and people put their faith in me—people who gave me their time, their energy, their presence. Realizing this, I felt I owed it to them to continue the work.

On a larger scale, we all witness society continually changing, sometimes incrementally but often quite quickly. I’m grateful to have witnessed some positive cultural shifts (gay marriage acceptance, electing a biracial president, increasing climate change awareness) while at the same time I’m often left speechless as I watch my fellow patriots embrace racism, deny science, and enable a police state.

As our country further divides, where does personal identity sit in all of this? And how much do people’s perspectives change over time? Revisiting this project gave me small windows with each participant to sit with these questions. I reconnected with people who, for the most part, were simply acquaintances (or even strangers); yet at the same time, also people with whom I’ve shared a real intimacy with.

It’s a personal dynamic I’ve never experienced before and it’s not just me. At the exhibition opening, I witnessed participants meeting for the first time, but they’ve also known each other’s faces and statements for decades. In some ways, they both know and don’t know each other. Adults got to meet other adults who had grown up seeing their image. Individuals got to hear how something they jotted down at a photo shoot profoundly affected someone else’s life.

What was the process like of reconnecting with the participants?

Logistically, quite difficult. Keep in mind that in the early 00s, people had flip phones (or no phones at all). And their email addresses were typically Hotmail or AOL accounts. By the time I began searching for people, most of the participants had changed their contact information or moved. Some had died. One thing I did discover was that every single person I eventually connected with was fully on board with re-participating in the project. That meant a lot to me.

How has working on this project changed you as a person?

Hard question, as so much else has personally occurred over a quarter century…I married and divorced, came close to death with sepsis, fell in love, and survived the deepest depression of my life. I also created the first college course on Spoken Word, and together with my colleague and mentor, Paul Spickard, started a critically important class titled Race & Masculinity. Both are classes I continue to teach.

Most importantly, I became a father to my two children, Jack and Pepper. And as important as making art is to my being, I can’t really parse it out from raising kids or teaching. I can say that overall, I am much more grateful for my role as an artist and as a guide. And that I have far less interest in arguing, especially online.

The core of this project was always human interaction and the human touch. It is the opposite of social media, the opposite of an online environment. I spend time and interact with every participant; they handwrite ink on actual paper, and they tell their story in their own words. I guess in that way, the project has changed me in that it has made me even less tolerant of online discussions and digital reviews, even as it has made me more thankful for real-life experiences.

A great deal is currently happening in the United States regarding identity, culture, and immigration. How do you think this project can contribute to the discussion?

If someone is truly able to tell their story, and another is truly able to hear it, we can start solving our problems. That’s not to say we still won’t have conflict—of course we will. But, the importance of developing the skill sets necessary to seek and cultivate shared values has been diminished, even discarded, by algorithms rewarding outrage and encouraging divisiveness and tribalism. And in this era of AI and the ever-increasing corporate ownership of media and information dissemination, I believe hearing and understanding the individual voice is a necessary foundation to saving our democracy. This may seem like a grandiose statement. Perhaps it is.

But in reality, this simple premise—hearing and understanding someone—is actually much more difficult than it seems. Most of us are actually unable to speak honestly about how we feel outside of anger—this is especially true of men. So we are functionally unable to tell our story with honesty and vulnerability. Listening and understanding is even harder, as our collective attention spans continue to shorten amidst a world of sensationalist “news” and TikTok brain.

In the 90s, I made a film about white men with Asian women that was intentionally hyperkinetic—back-to-back edits of Hollywood film clips plus multiple voiceovers, images, and crawling texts…purposely overwhelming. At the time, viewers complained that they couldn’t follow it. Today, it seems almost slow.

So I stick to the fundamentals with The Hapa Project. A simple, handwritten statement by participants along with the image of their choice, their pen to paper, a tactile photograph on a wall, or in a book. It may or may not reach millions, but when it does reach someone, it hopefully does so in a way that opens further thought, contemplation, or reflection—a process that is more than a swipe, click, or scroll.

And I am hopeful as I watch younger Gen Zs and older Gen Alphas embracing the idea of process and the beauty of investing time—valuing the ritual of shooting film or playing vinyl records and cassette tapes (when I was a teen there was nothing more important than buying a band’s new record, bringing it home, turning out the lights, and listening to the entire album). Maybe that makes me old. But I think there’s something valuable there we’ve collectively lost and need to reclaim.

What do you hope people who visit the exhibition or view the work online will take away from it?

I always hope they can see it in person. Or at least hold it in their hands.

Exhibition Information:

Kip Fulbeck

hapa.me – 25 years of The Hapa Project

May 23, 205–Summer 2027

Museum of Us

1350 El Prado, San Diego, CA, USA

Kip Fulbeck: Website | Instagram

My Modern Met granted permission to feature photos by Kip Fulbeck.

Related Articles:

Powerful Portraits Explore Zimbabwean Identities Through High Fashion

Artist Combines Floral Patterns and Portraiture to Explore Pan-African Identity

1,000 Refugees Share Their Hopes and Dreams in Powerful Portrait Series [Interview]

Powerful Portraits of Native Americans Highlight Their Spirit and Cultural Identity [Interview]