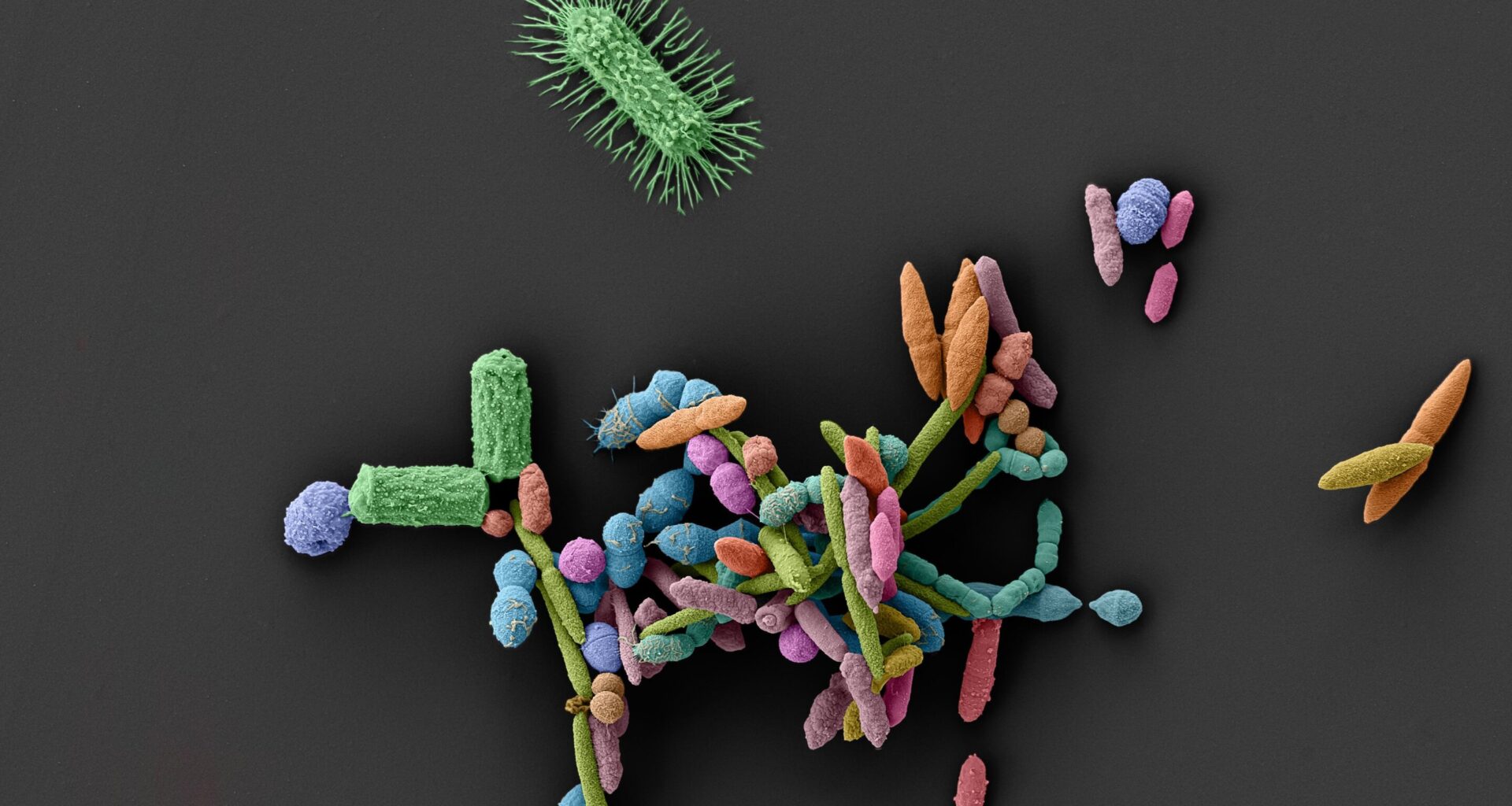

Scanning electron microscopy image of a gut bacterial community comprising (1:1.000.000). These interacting microorganisms form an ecosystem that is vital to human health. Medications can sever-ely disrupt this fragile balance – they eliminate beneficial bacteria and thereby promote the growth of harmful species.Credit: Image produced by the Maier Lab (Lisa Maier, Anne Grießhammer, Leonardo Boldt) together with the Tübingen Structural Microscopy Core Facility (Michaela Wilsch-Bräuninger, Stefan Fischer); Colouring: Elke Neudert.

The human intestine is home to a dense network of microorganisms, known collectively as the gut microbiome, which actively helps to shape our health. The microorganisms help with digestion, train the immune system and protect us against dangerous intruders. However, this protection can be disrupted, and not just by antibiotics, which—when used for treatment—are intended to prevent the growth of pathogenic bacteria.

A new study shows that many medications targeting systems in the human body can also change the microbiome so that pathogens can colonize the gut more easily and cause infections. The study, directed by Professor Lisa Maier of the Interfaculty Institute of Microbiology and Infection Medicine Tübingen (IMIT) and the Cluster of Excellence Controlling Microbes to Fight Infections (CMFI) at the University of Tübingen, has been published in Nature.

The researchers studied 53 common non-antibiotics, including allergy remedies, antidepressants and hormone drugs. Their effects were tested in the laboratory in synthetic and real human gut microbial communities. The result was that about one-third of these medications promoted the growth of Salmonella, bacteria that can cause severe diarrhea.

Maier, senior author of the study, says, “The scale of it was utterly unexpected. Many of these non-antibiotics inhibit useful gut bacteria, while pathogenic microbes such as Salmonella Typhimurium are impervious. This gives rise to an imbalance in the microbiome, which gives an advantage to the pathogens.”

Pathogens remain, protective bacteria vanish

The researchers observed a similar effect in mice, where certain medications led to greater growth of Salmonella. The consequence was severe disease progression of salmonellosis, marked by rapid onset and severe inflammation.

This involved many layers of molecular and ecological interactions, report the study’s lead authors, Anne Grießhammer and Jacobo de la Cuesta from Maier’s research group: Medications reduced the total biomass of the gut microbiota, harmed biodiversity or specifically eliminated microbes that normally compete for nutrients with the pathogens. This resulted in a change in the microbiome, creating a more favorable environment for pathogenic microbes such as Salmonella, which were then able to proliferate unimpeded.

“Our results show that when taking medications we need to observe not only the desired therapeutic effect but also the influence on the microbiome,” says Grießhammer. “While the necessity of drugs is unnegotiable, even drugs with supposedly few side-effects can, so to speak, cause the microbial firewall in the intestine to collapse.”

Maier adds, “It’s already known that antibiotics can damage the gut microbiota. Now we have strong signs that many other medications can also harm this natural protective barrier unseen. This can be dangerous for frail or elderly people.”

Call to revise assessments of drug effects

The researchers recommend that the effect of medications on the microbiome should be systematically included in research during development—especially for drug classes such as antihistamines, antipsychotics or selective estrogen-receptor modulators as well as for combinations of several medications.

Maier’s team has developed a new high-throughput technology, which quickly and reliably allows testing of how medications influence the resilience of the microbiome under standard conditions. These findings call for pharmaceutical research to be rethought: in the future, medications should be assessed not only pharmacologically, but also microbiologically.

“If you disrupt the microbiome, you open the door to pathogens—it is an integral component of our health and must be considered as such in medicine,” stresses Maier.

President Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. (Dôshisha) Karla Pollmann emphasizes, “Microbiome research in Tübingen has made an important discovery here. If the effect on the microbiome is incorporated in the development of medicinal products, the hope is that in the long term, patients could receive more suitable treatments with reduced side effects.”

More information:

Anne Grießhammer et al, Non-antibiotics disrupt colonization resistance against enteropathogens, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09217-2

Provided by

University of Tübingen

Citation:

Unexpected side effect: How common medications clear the way for pathogens (2025, July 16)

retrieved 16 July 2025

from https://medicalxpress.com/news/2025-07-unexpected-side-effect-common-medications.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.