“I have Type 1 diabetes.”

Miles Byrd is no longer ashamed to say it.

San Diego State’s fourth-year guard was first diagnosed in eighth grade after, of all things, stubbing his foot and breaking two toes on one of his repeated trips to the bathroom.

A close family friend had been rushed to the hospital two years earlier, also in eighth grade, with dangerously high blood sugar levels and diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes. Byrd’s mother noticed suspicious behavior in her son — craving water, urinating frequently — and, after his toes were X-rayed, asked the doctors to check his blood sugar levels.

It was skyrocketing. Good thing he was already at a hospital.

That began Byrd’s lifelong journey with the chronic condition where your immune system mistakenly attacks the pancreas’s insulin-producing capacity that facilitates the transfer of glucose (or sugars) to cells. He has dealt with it for eight years. Only now is he dealing with it publicly.

Byrd signed an NIL deal with Dexcom, a San Diego company that makes the continuous glucose monitoring devices he’s worn since age 13. Last week, he attended a camp for kids with diabetes in Baltimore as part of Dexcom U, a program with 21 college athletes who, a company press release states, “are breaking boundaries in sports and achieving their goals, despite their diagnosis.”

Type 1 diabetes differs from Type 2 in that the former typically has an earlier onset and requires regular insulin supplementation for life, either through injections or a pump. Type 2 is more prevalent and less severe, often treated through diet and medication.

Byrd told hardly anyone — not in junior high, not through four years of high school, not when he first arrived at SDSU in 2022 as a skinny 17-year-old from Stockton. He hid his glucose monitor on his lower back, under his shorts, instead of the more common, more conspicuous location on the underside of the upper arm.

“I was very secretive about it,” Byrd said in a free-flowing, candid, introspective conversation earlier this week. “My mother always encouraged me not to be, but I was always a shy kid who didn’t want to talk about diabetes. I never went to those camps to meet other kids with diabetes. I was like, ‘I don’t want to meet them. I don’t want anybody to know.’

“I think it was partly just that I didn’t want people looking at me differently. I’m a basketball player. I wanted to be known as a basketball player, not a diabetic basketball player. Now I realize I’m a diabetic basketball player who can inspire generations below me who maybe just got diagnosed and don’t know what the future looks like for them, who might think it could eliminate a dream.”

SDSU’s Miles Byrd is treated by athletic trainer Sergio Ibarra during the NCAA Tournament game against North Carolina last March. (K.C. Alfred / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

SDSU’s Miles Byrd is treated by athletic trainer Sergio Ibarra during the NCAA Tournament game against North Carolina last March. (K.C. Alfred / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

His Aztecs teammates probably suspected something when, during practice, Byrd would be summoned by athletic trainer Sergio Ibarra to the side and handed an orange, or a handful of gummy bears, or maybe a cup of sugary Gatorade. Or he would suddenly disappear into the locker room. Or suddenly become fatigued, sapped of his usual effervescence.

It’s all part of the delicate dance of diet, exertion, hydration and insulin that Byrd lives with weekly, daily, hourly.

The adjustment to college was rough at times, living on his own away from his parents and their medical oversight, calibrating his insulin injections with new eating and sleeping habits. It was a major reason he was granted a medical redshirt for his freshman season despite appearing in four nonconference games.

“If he needs to come out and get some assistance from Sergio, he does that,” coach Brian Dutcher said. “I let them manage it, but he does a magnificent job doing it. You wouldn’t know, unless you knew.”

His glucose biosensing monitor is linked to his and Ibarra’s mobile phones, with a goal of 120 milligrams per deciliters. When his blood sugar level drops into double digits, he eats a snack or drinks Gatorade to raise them. When it spikes, he injects insulin into his abdomen to lower them.

He briefly tried an insulin pump but found it too bulky. He prefers injections, which he administers himself — “I’m not freaked out by needles” — between five and 10 times per day. He uses two types of insulin, a fast-acting one before meals and another, longer-lasting one before bed.

If you see Byrd carrying his phone to the bench, he’s not a vain “screen-ager.” It must be as close as possible to the glucose monitor to receive real-time readings.

If you see Ibarra standing next to him during timeouts, it’s because Ibarra carries Byrd’s phone at games and they need to re-establish connection with the device if, while on the court, he strays too far away.

If you see Byrd sub out of a game and rush to the locker room, it’s not a bathroom break or tending to an injury. His phone alarm went off for abnormal levels, and he needs a shot or a snack. The Feb. 22 game at Utah State was a big step forward; Byrd allowed Ibarra to hold up a towel and inject him during a timeout instead of making the lengthy trek across the court and up a ramp to the locker room.

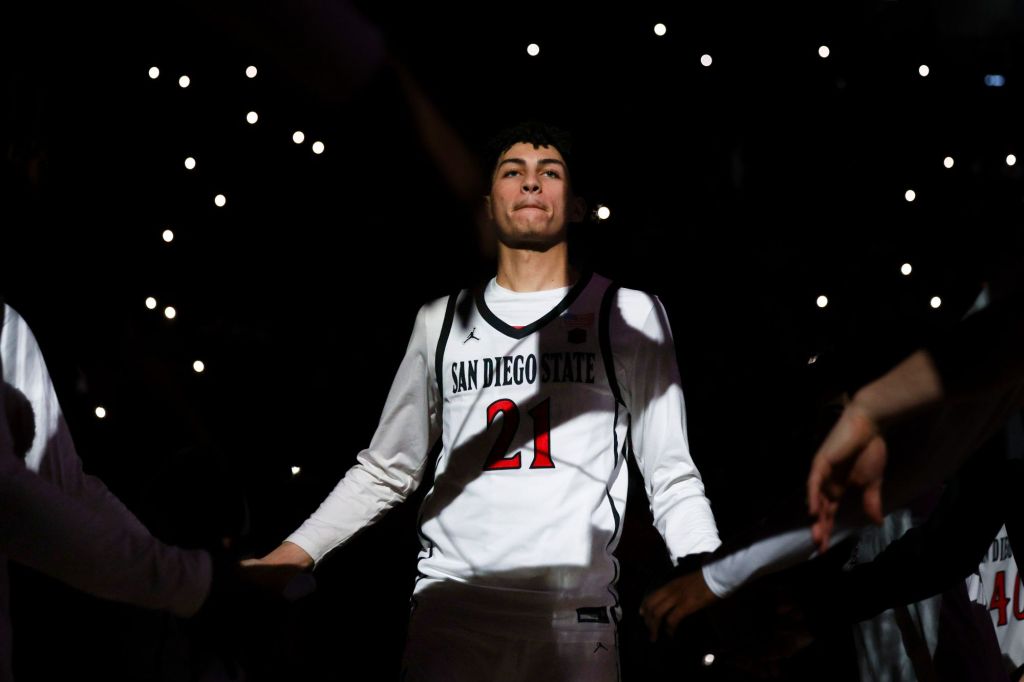

San Diego State guard Miles Byrd (21) shoots over Fresno State guard Zaon Collins (10), Feb., 18, 2025 in San Diego, Calif. (Photo by Denis Poroy)

San Diego State guard Miles Byrd (21) shoots over Fresno State guard Zaon Collins (10), Feb., 18, 2025 in San Diego, Calif. (Photo by Denis Poroy)

The Mountain West’s many high-altitude venues, Byrd learned last season as his playing time increased significantly, can play havoc on a sea-level athlete with Type 1 diabetes.

“Your body is using a lot more energy, and my blood sugars would spike really high,” Byrd said. “You can’t focus. You get tired really quickly. My endurance is a fourth of what it usually is. Colorado State got pretty bad. I went to the locker room twice at Air Force.”

After 25 points, six rebounds and seven steals against Colorado State at Viejas Arena three weeks earlier, Byrd had seven points on 2 of 11 shooting in a 68-63 loss against the Rams at Moby Arena, elevation 5,023 feet. He had eight points on 2 of 9 shooting at Air Force, elevation 7,080 feet.

In six games above 4,500 feet last season, he shot 19% behind the 3-point arc, compared to 33.6% everywhere else.

“I think when he first got here, he was trying to be secretive about his condition,” Dutcher said. “He didn’t want to show the other guys what he was dealing with. He’d sneak out of the meeting room or team meal and get an injection and manage his diabetes. To see him now step up and embrace that he has it, to let others know you can function at a high level with it, I think is a credit to Miles and his journey.”

Type 1 diabetes, by some estimates, afflicts more than 1 million Americans but accounts for less than 10% of all diabetes cases. That includes only a handful of professional athletes, most notably Torrey Pines High alum and former NBA center Chris Dudley; SDSU alum and 2025 U.S. Open golf champion JJ Spaun; Olympic swimmer Gary Hall Jr.; and Baltimore Ravens tight end Mark Andrews.

The Dexcom U camp was hosted by Baltimore Ravens tight end Mark Andrews in Baltimore last week, with SDSU’s Miles Byrd and 20 other college athletes with Type 1 diabetes. (Photo courtesy of Dexcom)

The Dexcom U camp was hosted by Baltimore Ravens tight end Mark Andrews in Baltimore last week, with SDSU’s Miles Byrd and 20 other college athletes with Type 1 diabetes. (Photo courtesy of Dexcom)

The Dexcom U camp in Baltimore last week was hosted by Andrews. Among the college athletes there was 6-foot-10 Creighton forward Isaac Traudt, who played against Byrd and the Aztecs last November in the Players Era Festival in Las Vegas.

Byrd admits being apprehensive when he first arrived but quickly relaxed after meeting other college athletes in the hotel lobby and sharing their stories, fostering an instant kinship he never had. A glucose monitor phone alarm dinged. They all laughed.

“It’s like, ‘Is that my phone?’” Byrd said. “I’ve never been in a setting like that, where everybody has the same thing. ‘Wait, that’s not my phone. It’s your phone.’”

Byrd is the highest profile college athlete on the Dexcom U roster and plays in the backyard of the company’s Sorrento Valley headquarters. He figures to command the most attention from his decision to step forward.

He’s ready for it.

“I don’t want to be the guy to explain diabetes,” Byrd said. “I just want to be the guy who’s there for them, a guy they can look at and see that he has Type 1 diabetes and he’s doing this. I just want to be an example and role model. I don’t know think I’m a diabetes educator. I know a good amount about it, but I’m not smart enough to teach somebody else what they need to do based on what their body is telling them.

“I just want to inspire people. I don’t want people to take the approach I did, where I was scared to inspire. I just want it to be something that people aren’t ashamed to talk about.”