His long home run might not have resonated around the sport, but as Chris Carter rounded the bases in Campeche, Mexico last week, he knew what he’d just accomplished.

Now 38 years old, Carter had long dreamt of this moment coming in the Majors, and that made some sense; he’d hit 158 big-league homers by age 30, even if the last one of those came eight years ago. In that reality, he’d soak in an adoring crowd’s appreciation, while the baseball world awed over his milestone. In his mind, that should have been how his 500th professional home run was received.

Instead, it was just his teammates who cheered in support from the dugout. A reliever in the bullpen leapt the left field fence, where there were no stands and no fans, to race and fetch the ball. His homer was like a scene out of Bull Durham, with Carter a modern-day Crash Davis. Appreciated by the few that knew, but unnoticed by everyone else.

“I try not to let myself wander to that,” Carter said. “‘Why am I not there?’ Because everything happens for a reason. And for whatever reason, I ended up here, and I’m still playing. I’m thankful to still be playing here.”

Drafted out of high school in 2005 in the 15th round by the Chicago White Sox, Carter has been hitting home runs wherever he’s played for two decades. The minor leagues, the majors, indy ball, or, in this case, Mexico, and his current team, the Piarates de Campeche.

In some respects that’s been his blessing and his curse. A three-true-outcomes hitter, long balls got him to the Show, but strikeouts booted him out. Beloved for one skill, but maligned for the deficiency that accompanied it. After he hit the 500th home run of his long and polarizing career, he felt the joy of it, and the weight of it all at the same time.

“I do think there’s a part of it that’s a little bit heartbreaking, that it wasn’t at the major-league level. That it is in a different country,” said Carter’s longtime agent Lonnie Murray. “Do I think it means something? Absolutely. But I think it’s also a reminder of a career cut short.”

Carter’s big-league career with the A’s, Astros, Brewers and Yankees was a fever dream. In his four full seasons, he averaged 33 home runs, and hit 158 total over 750 career games. But by age 30, he was out of the league for good. For no other reason than he was no longer wanted.

Murray argued with Major League general managers. After Carter hit a National League-leading 41 home runs for the Milwaukee Brewers in 2016, he was non-tendered. “He wasn’t, and I quote, ‘in the plan,’” she said. “Well, what is the plan?”

Carter signed with the Yankees ahead of the 2017 season, but was released after hitting .201 with eight home runs and a .653 OPS in 62 games. He bounced around the minors for the next year, but in 2019, he headed to Mexico.

When he looks around the sport nowadays, Carter sees hitters just like him. When he looks back at his own tenure, he remembers a media that he believes highlighted his failures and ignored his successes.

“It was definitely tough,” Carter said. “Every time you see an article, it was ‘Chris went 2-for-4 with a homer and a double, and then, a strikeout.’ Well why did they put ‘strikeout’? What was the point of that? They would put an emphasis on that, and try to make it more than what it was.”

The difference, however, was less in the media and more on the margins. Hitters like Joey Gallo and Kyle Schwarber have the same skills and weaknesses that Carter had. But Schwarber’s strikeout rate is 28 percent, while Carter struck out in exactly one-third of his big-league plate appearances. The major league average is 22 percent this season, and was 21 percent in Carter’s last full year.

Gallo and Carter have a nearly identical home run rate. But Gallo has 41 career defensive runs saved, according to FanGraphs, and Carter has -31 DRS. Defense played a large role in how Carter was viewed.

But what bothered Murray most was a perception from teams and executives that her client didn’t care, or was unemotional about his own career. After playing seven years of punishing baseball in Mexico for $180,000 a season, that assumption has long been disproven.

“Clearly you have to be passionate about what you’re doing to be almost 40 years old,” she said, “still playing the game, and going to a different country to do it.”

In his MLB days, Carter mashed homers for the Athletics, Astros, Brewers and Yankees. (Stacy Revere / Getty Images)

While it’s nearly impossible to find out exactly how many players have hit 500 professional home runs, the feat is incredibly rare. Only 28 have done it at the big-league level, with a large handful of them connected to the use of performance-enhancing substances.

There are plenty more that have nearly 500 big-league homers, with enough in the minor leagues to help clear the threshold. Think Adrian Beltre or Adam Dunn. There are eight more who reached 500 home runs in Japan, without ever playing affiliated baseball.

Seldom, however, has anyone reached 500 professional home runs using Carter’s blueprint. Karl “Tuffy” Rhodes hit 13 big league bombs, 54 more in the minors and 464 in Japan. Similar paths were followed by Alex Ramirez and Alex Cabrera, who had brief big-league stints but legendary careers overseas.

That is Carter’s category. But, perhaps, there’s no one quite like Carter.

“It’s just the longevity, and being able to play this game,” Carter said. “Everyone I got drafted with, all the friends I played with, there are only a couple guys still playing. I’m just fortunate to still be playing, and putting up these numbers and be in this conversation.”

Most players travel south of the border in the hopes of coming back to affiliated baseball someday. Carter has long given up on that hope. Once he hit 49 homers in 2019, without a single call from any of the 30 teams, it was evident none would ever come.

He’s willing to stay in Mexico as long as he’s wanted. But the closest he’ll get to an MLB audience is the handful of Houston Astros fans who make the trip to see him play every year in Laredo, Texas. This is his baseball existence now. He’s accepted it, embraced it, and kept going all the way to the 500 home runs, plus the two more he’s crushed in the days since.

Carter has always been soft-spoken and matter-of-fact. Even as he talks about 500 homers, his quiet and nonchalant tenor could convince you it’s no more important than any of those that came before it.

But to understand what 500 means, it requires rewinding all the way back to his first home run. It came in 2005, while Carter was an 18-year-old playing rookie ball for the Bristol White Sox.

“He could be in the room, and if you didn’t look back, you wouldn’t know he was there,” said his manager, Jerry Hairston Sr. “He was so quiet and shy. I was just trying to get him out of his shell and be a tougher guy.”

He believed that Carter needed to get a little meaner, and told him to find something, anything to rile him up. It could be real or fake, but he had to believe it. Imagine the pitcher saying something bad about his mother, Hairston suggested. Whatever it took.

One game, this came to fruition. A pitcher came up and in on the young Carter, forcing him to the ground to avoid a devastating hit by pitch. “He’s dusting himself off, and he’s looking at that kid,” Hairston said. “He could hardly speak, he was so mad at this guy.”

The next at-bat, Hairston remembers vividly to this day, Carter came up to face the same pitcher.

“He hit this ball into the night,” the manager recalled. “Past the lights, over the little field (beyond the fence). I’m just watching. The world stopped after he hit that thing. That’s Chris Carter right there.”

That’s who Carter became. And 20 years later, it’s who he still is. Still shy and soft spoken. And in some ways, still a little angry too.

He kept that ball he hit 20 years ago, still encased in his home, alongside No. 100 in the Majors, No. 100 in Mexico, and a slew of other random balls he’s saved over the years.

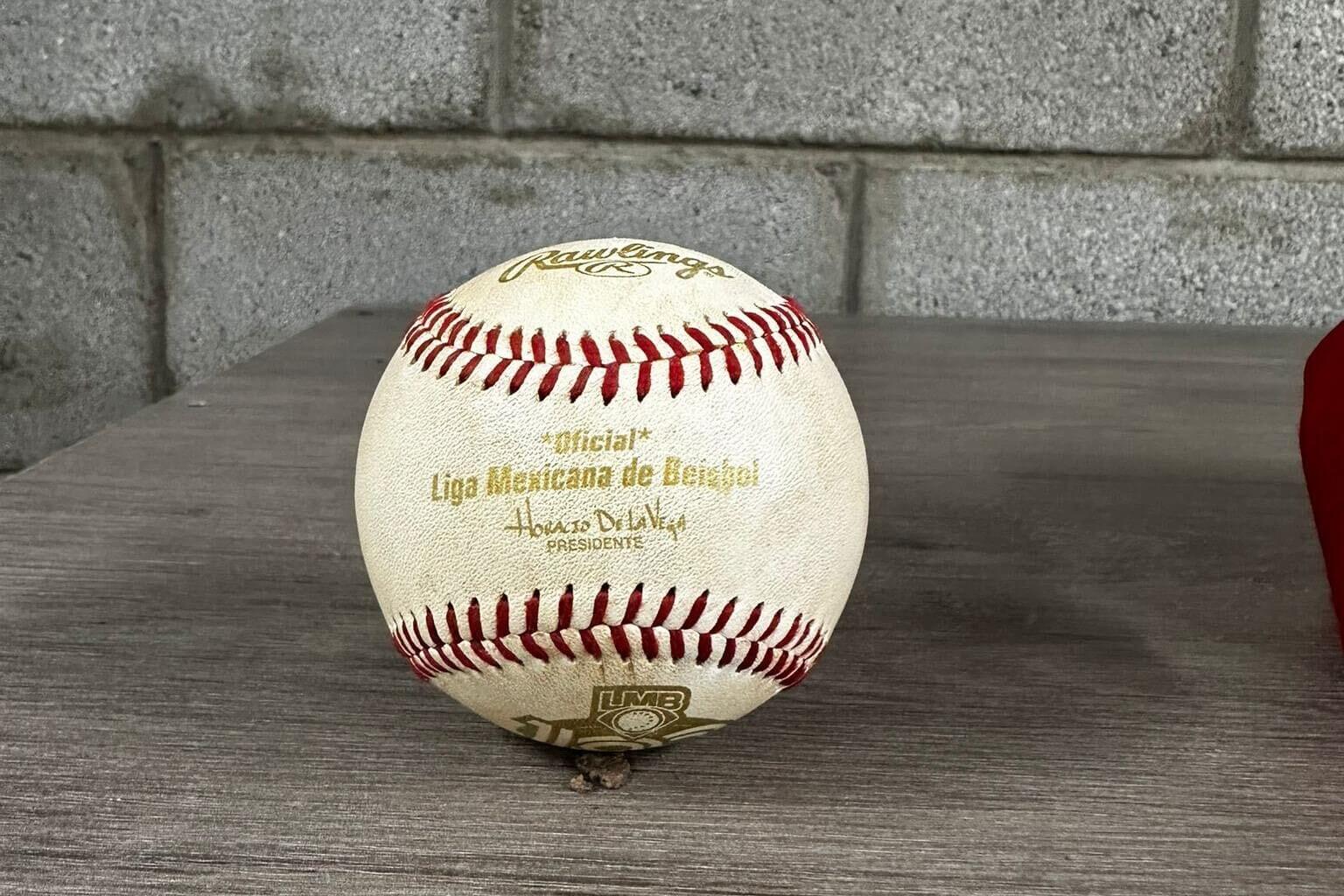

Carter’s 500th home run ball. (Courtesy of Chris Carter)

Number 500 will go up there too. A reminder of a long and fulfilling career, but also of the disappointment that accompanied it. As that ball rests atop his mantle to be picked up and looked at, it’s a tangible representation of everything he’s accomplished. Something no one can take from him.

“It’s one of those things where if you don’t do it in the states or in the big leagues, it’s not as important to some people,” Carter said. “But for me, it’s a huge accomplishment. Five hundred anywhere is still 500. You’ve still got to hit it.”

(Top photo of Carter in the 2024 Mexican Baseball League home run derby: Eyepix / NurPhoto via AP)