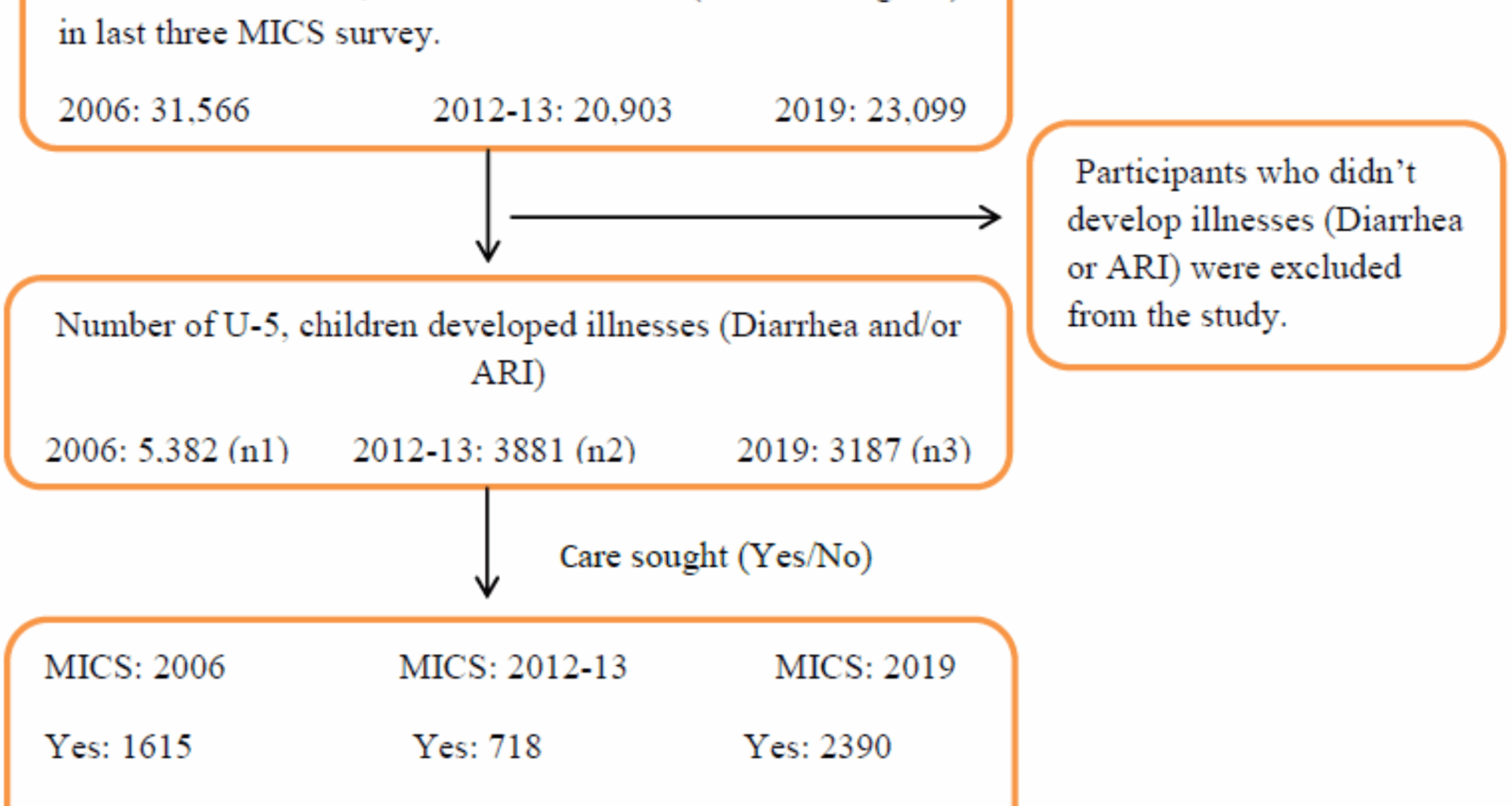

This study aimed to analyze the trends in healthcare-seeking behavior for childhood illnesses and identify the factors contributing to inequalities in healthcare-seeking among children under 5 in Bangladesh. Using data from the last three rounds of the Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) conducted in 2006, 2012–13, and 2019, we explored how care-seeking behaviors have evolved and the key determinants driving these trends. This study’s focus aligns with the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 10, which emphasizes reducing inequalities. By identifying the factors influencing unequal healthcare access, particularly for children with Acute Respiratory Infections (ARI) and diarrhea, this study highlights the critical need for targeted interventions to improve healthcare utilization and reduce disparities.

Our findings revealed a significant decline in care-seeking behavior from 2006 to 2012–13, dropping from 30 to 18.5%. This decline may be attributed to the higher illness prevalence and reduced healthcare utilization among the poorest quintiles during this period. However, care-seeking behaviors improved substantially by 2019, reaching 74.6%. This improvement is likely due to enhanced healthcare infrastructure, increased availability of healthcare facilities, and greater awareness of the importance of seeking medical care [56]. Despite these improvements, disparities persist across socioeconomic, demographic, and regional factors, underscoring the need for equitable and targeted health care policies.

The analysis revealed significant socioeconomic and demographic factors, including gender, region, and child’s age, that impact care-seeking behavior over time. Gender significantly influenced unequal healthcare utilization, with more care sought by male children than by female children. Disparities in care-seeking behaviors based on gender, where male children are prioritized over female children, have been substantiated by several studies conducted in Bangladesh [20, 23, 25, 27]. Similar findings have emerged from research in India [57] and other developing countries [26, 28, 36]. This pattern explains the prevalence of son preference in Bangladesh and other developing nations, where economic constraints often limit women’s decision-making roles. A multi-year hospital surveillance study in Bangladesh revealed that employed women are more inclined to seek healthcare for their daughters [23]. However, different findings were observed in two earlier studies conducted in Bangladesh [24, 39].

The analysis also showed significant disparities in care-seeking behaviors across the different divisions. All divisions sought significantly more care than the Dhaka division, with the Sylhet division seeking the least. These differences can be attributed to factors such as the high number of slum dwellers and floating populations residing in Dhaka, and the accessibility of community clinics in other divisions [58]. Additionally, the lower care-seeking behavior in the Sylhet region may be attributed to the lower percentage of empowered women (48%) compared with other regions, which could impact decision-making and healthcare access [41]. Furthermore, a study conducted by Ahmed and Yunus, 2020 [21] reported that significantly less care was sought in the Sylhet region, as well as the regional impact on care-seeking behavior noted by Khanam & Hasan, 2020 [16]. Children aged 12–23 months tend to seek significantly less medical care than those aged 0–11-month age group. This trend may be because younger infants are at a higher risk of developing severe health conditions than older infants. Numerous studies have reported similar findings, highlighting that younger children seek more medical attention than older children [6, 7, 16, 21, 25, 26, 28, 29]. The impact of a mother’s education on care-seeking behavior was insignificant in 2006 but became significant in 2012-13 and 2019.

Mothers with primary education sought healthcare significantly more often than their uneducated counterparts did. Two previous studies conducted in Bangladesh [16, 21] found that mothers with higher levels of education were more inclined to seek medical care than those with less education. This trend has also been observed in other developing countries [6, 7, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34]. The disparity arising from maternal education is due to educated mothers having a better grasp of illness signs and symptoms, understanding the severity of health issues, and the significance of prompt healthcare, all of which motivate them to seek medical attention for their children [6, 21]. However, contrasting evidence was reported by Sarker et al. [20], who found that mothers with secondary education sought less care than those without, indicating a negative association.

The analysis also revealed that household head’s education and wealth were insignificant in 2006 and 2012–2013. However, these variables were found to be significant in 2019. In particular, households with heads who had completed secondary education demonstrated a greater likelihood of seeking healthcare than those with illiterate heads. This trend can be attributed to the understanding that higher education improves access to knowledge, while better financial status facilitates greater access to healthcare services. Previous studies have shown patterns similar to those identified in our analysis [6, 22, 28, 29, 32, 35, 36]. Wealth was identified as a significant factor influencing unequal care-seeking behaviors in childhood illnesses. Households with greater financial resources tended to seek healthcare more frequently than those with limited resources. Financial constraints can hinder access to healthcare services and exacerbate household wealth inequalities. These findings are consistent with results from other studies [7, 20, 25, 26, 29, 30, 36, 37, 54].

Ethnicity significantly influenced care-seeking behaviors. Individuals from ethnic minorities tend to seek healthcare less frequently than their Bengali counterparts, likely due to lower literacy rates (50.1% for ethnic minorities versus 68.1% for Bengalis) [43]. Furthermore, lack of facilities and limited opportunities can create barriers to accessing care.

Data regarding childhood stunting were unavailable in 2006, but a considerable association with care seeking was noted in 2012-13, which became insignificant by 2019. Similarly, the number of children under five showed significant associations in the earlier two study periods, but lost significance in 2019. The presence of handwashing facilities was significant only during 2012-13 and was deemed insignificant in 2019. This trend may be linked to rising education levels among household heads, particularly at the secondary level, as well as among mothers at both secondary and higher educational levels, as indicated by the MICS data. These changes may stem from the aforementioned factors.

Additionally, the government of Bangladesh initiated the Access to Information (a2i) program as part of the ‘Digital Bangladesh’ initiative, aimed at ensuring the availability and accessibility of all public services [59]. In this context, well-educated individuals are expected to have better access to relevant information. The influence of area of residence, religion, and breastfeeding status was insignificant across all three study periods.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study had several strengths. Analyzing data from three rounds of nationally representative Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) conducted in 2006, 2012–13, and 2019 offers a robust examination of trends in healthcare-seeking behavior for childhood illnesses over 13 years. By emphasizing disparities in healthcare access, this study aligns with global priorities such as Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 3 and SDG 10) and highlights critical socioeconomic, demographic, and regional inequalities. The use of a large, nationally representative dataset enhances the generalizability of the findings, while the examination of multiple determinants, including gender, region, age, and maternal education, offers a multidimensional perspective on the drivers of inequality. Additionally, policy-relevant findings identify actionable areas for intervention, such as addressing gender bias, improving healthcare access in underserved regions such as Sylhet, and promoting maternal education to reduce disparities and enhance child well-being.

Despite its strengths, this study had some limitations. First, it did not account for seasonal variations in healthcare-seeking behavior as the necessary data were unavailable. Seasonal factors, such as the prevalence of certain illnesses during specific times of the year, could influence healthcare utilization, and future studies could explore these variations. Second, although this study conducted a trend analysis, the data were cross-sectional and collected from the Bangladesh Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS). As a result, causality cannot be established, and we cannot definitively conclude that the identified factors are the direct causes of inequality in healthcare access. Longitudinal studies can help identify causal relationships and allow a deeper understanding of how these factors evolve. Additionally, this study did not capture all potential determinants of care-seeking behavior, such as the quality of healthcare services, which could significantly impact decisions to seek care. Future research could incorporate these factors and explore the role of health care quality, infrastructure, and cultural norms in shaping inequalities in care access. Furthermore, the study did not address the unique challenges faced by marginalized or disadvantaged populations. Future work should focus on understanding the healthcare needs of these groups and assessing the effectiveness of policies aimed at improving healthcare access for these populations. Mixed-method approaches, combining quantitative data with qualitative insights, could provide a more comprehensive picture of the barriers to care and effectiveness of interventions.