Under the midsummer sun at Conundrum Farms, Ka’Miyah Roberts, 15, stood across from a teenager from Eswatini and listened as they talked about how food is shared in their home.

For Ka’Miyah, a FunkyTown Food Project summer intern, it was her first time hearing how other countries handle hunger, and how much they do with less.

“It was a great experience,” she said. “I enjoy being able to hear from other people in their cultures.”

The event was part of a collaboration between FunkyTown Food Project and Fort Worth Sister Cities’ Global Leaders in Action. They brought together local youth and international students from Indonesia, China, Italy, Eswatini and the Dallas-Fort Worth area to explore leadership and community impact.

They toured the farm, shared lunch and sat down for candid conversations on food culture and food insecurity. Teens led five discussion zones, raising awareness on access, inequality and local-global food systems.

Interns grounded the discussion in data, noting that Texas leads the nation in food insecurity, with North Texas ranking third among metro areas, according to the North Texas Food Bank.

Kent Bradshaw, FunkyTown Food Project chief operating officer, said the day wasn’t just about farming, it was about perspective.

“If you don’t understand you’re part of a larger community, you’re never going to see the humanity and impact you could make on the environment,” Bradshaw said.

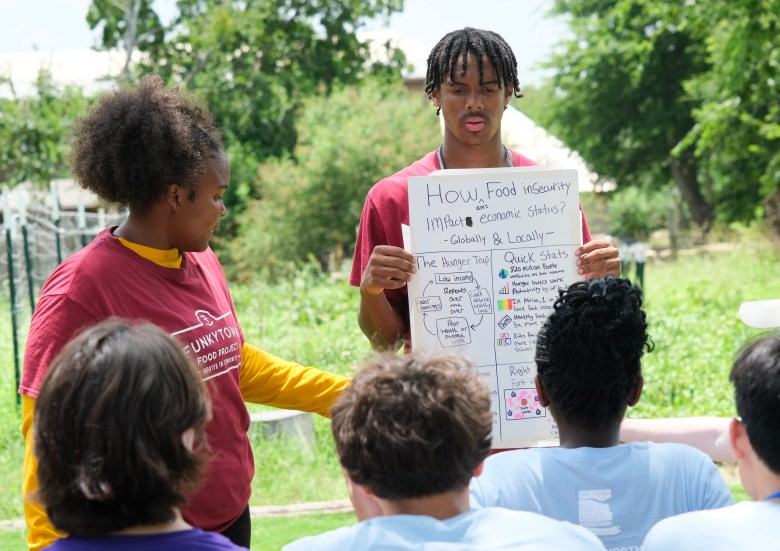

Ka’Miyah Roberts, 15, and Raheem Kenerly, 16, engage teens from Fort Worth Sister Cities and Global Leaders in Action in a discussion on food insecurity, July 16, 2025, in Crowley, TX. (Orlando Torres | Fort Worth Report)

Ka’Miyah Roberts, 15, and Raheem Kenerly, 16, engage teens from Fort Worth Sister Cities and Global Leaders in Action in a discussion on food insecurity, July 16, 2025, in Crowley, TX. (Orlando Torres | Fort Worth Report)

The FunkyTown Food Project, now in its fourth year of summer programming, offers a paid six-week internship to high schoolers 14 to 17. They learn sustainable agriculture, social justice topics and more.

But it also challenges them to think critically about the systems that feed or fail their communities.

Many students don’t know where their food comes from, or why healthier options are often out of reach, Bradshaw said. They learn about the corporate food system, and how large subsidies prop up processed food ingredients while fruits and vegetables remain underfunded.

“It just doesn’t match up,” Bradshaw said. “Other countries are not like that.”

His point echoes a 2022 Farm Action report that found a glaring contradiction in U.S. food policy: Federal subsidies heavily support commodity crops like corn and soy, often processed into high-fructose corn syrup and meat feed, while government dietary guidelines recommend diets rich in fruits and vegetables.

The disconnect has consequences. Poor diets contribute to rising rates of diabetes and cardiovascular disease in the U.S., according to the National Library of Medicine.

Bradshaw said the disparities are especially visible in Fort Worth. He pointed to the contrast between ZIP codes 76107, one of the city’s wealthiest, and 76104, one of the state’s poorest. The 76104 is a historically Black neighborhood where the life expectancy is 12 years below the national average.

Residents in 76104 lack access to healthy foods, among other challenges. Often, wealthy kids don’t realize this is happening in their own backyard, Bradshaw said.

Youth leaders from FunkyTown Food Project and teens from Fort Worth Sister Cities and Global Leaders in Action participated in games and conversation, July 16, 2025, in Crowley, TX. (Orlando Torres | Fort Worth Report)

Youth leaders from FunkyTown Food Project and teens from Fort Worth Sister Cities and Global Leaders in Action participated in games and conversation, July 16, 2025, in Crowley, TX. (Orlando Torres | Fort Worth Report)

That’s where programs like Global Leaders in Action come in. Paige Collins, youth and education manager for Fort Worth Sister Cities, said the two-week summer initiative helps teens explore topics such as education, sustainability and food insecurity, all through a leadership lens.

“Part of it is getting to know someone as a person, not just where they’re from,” Collins said. “They can take what they learned here and put those skills to use in their country or their communities back home.”

For Ka’Miyah, that means continuing to have conversations, and maybe growing more food. She said she was inspired by hearing how Eswatini students share food with those in need, instead of letting food go to waste.

As the group wrapped up discussions, Bradshaw stood nearby, watching the students laugh, play and exchange stories. For him, the day wasn’t just about teaching, it was about passing something on.

No matter the size of the group, tackling food insecurity starts with people and change, Bradshaw said.

And for Ka’Miyah, that change might start with gardening seeds.

Orlando Torres is a reporting fellow for the Fort Worth Report. Contact him at orlando.torres@fortworthreport.org.

At the Fort Worth Report, news decisions are made independently of our board members and financial supporters. Read more about our editorial independence policy here.

Related

Fort Worth Report is certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative for adhering to standards for ethical journalism.

Republish This Story

Republishing is free for noncommercial entities. Commercial entities are prohibited without a licensing agreement. Contact us for details.