Sometime in their cosmic lives, two gigantic black holes crashed into one another to form something even more monstrous: A black hole equal to the size of 240 of Earth’s sun.

Now, thanks to an international collaboration among physicists, cutting-edge technology managed to uncover the behemoth by detecting ripples in space-time from the violent collision.

The force of the collision not only left cosmic bread crumbs for researchers to follow, but created what experts claim is the most massive black hole merger ever observed through gravitational waves, or distortions in space-time caused by such powerful events.

As a result, physicists are rethinking their astrophysical models for the universe.

“It presents a real challenge to our understanding of black hole formation,” Mark Hannam, a physicist at Cardiff University in the United Kingdom who was part of the team behind the find, said in a statement. Black hole mergers “this massive are forbidden through standard stellar evolution models.”

What are black holes?

Supermassive black holes, regions of space where the pull of gravity is so intense that even light doesn’t have enough energy to escape, are often considered terrors of the known universe.

When any object gets close to a supermassive black hole, it’s typically ensnared in a powerful gravitational pull. That’s due to the event horizon – a theoretical boundary known as the “point of no return” where light and other radiation can no longer escape.

As their name implies, supermassive black holes are enormous (Sagittarius A*, located at the center of our Milky Way, is 4.3 million times bigger than the sun.) They’re also scarily destructive and perplexing sources of enigma for astronomers who have long sought to learn more about entities that humans can’t really get anywhere near.

Merger created enormous black hole the size of 240 suns

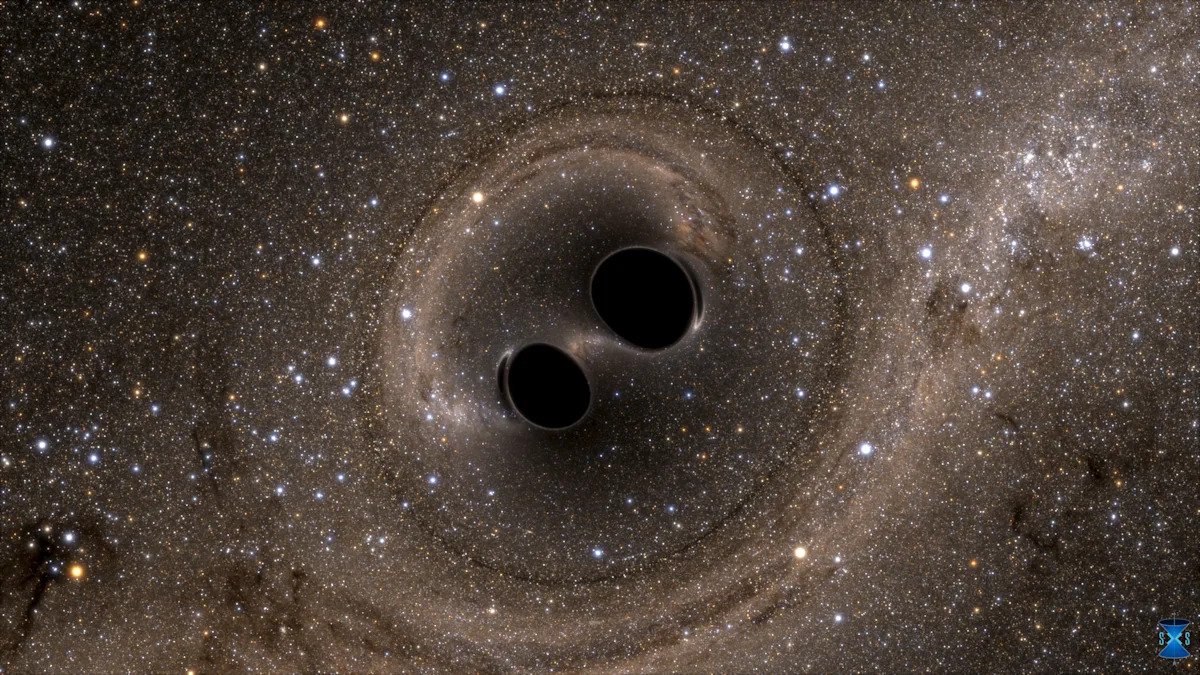

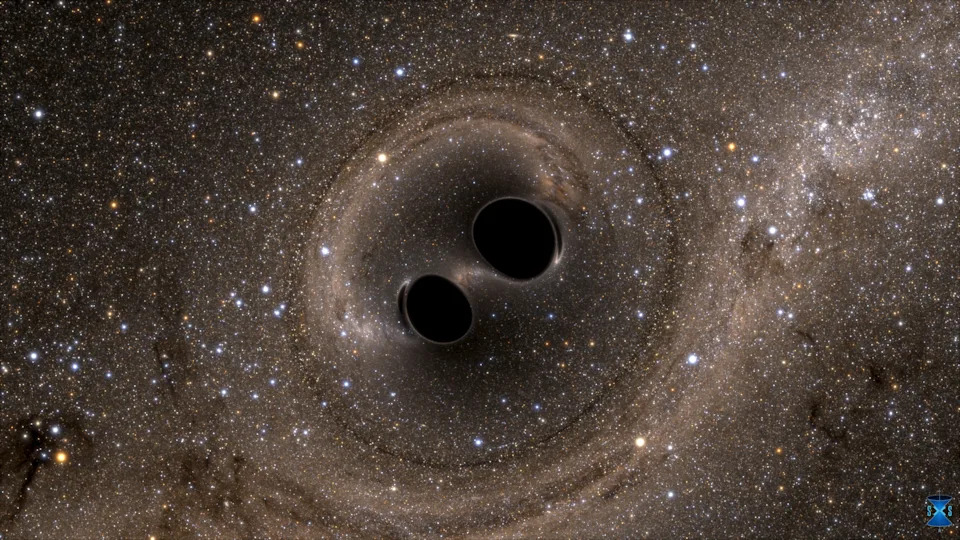

The collision of two black holes – a tremendously powerful event detected for the first time ever by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory, or LIGO – is seen in this still image from a computer simulation released in 2016.

The event, designated GW231123, was spotted Nov. 23, 2023, by the gravitational wave detector network LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA (LVK). An international team of physicists who are part of the network used detectors located in the United States, Italy and Japan to observe the merger through gravitational waves, a cosmic phenomenon that could hold clues about the mysteries of the universe.

First theorized in 1916 by Albert Einstein, gravitational waves are ripples in the fabric of space-time created during some of the universe’s most powerful events, including the merging or collision of supermassive black holes.

In this instance, two enormous black holes – 100 and 140 times the mass of Earth’s sun – collided. The result? A black hole the size of a whopping 240 suns.

That makes it the heaviest of all the previous approximate 100 black hole mergers yet confirmed through gravitational wave observations, according to the researchers. Until the discovery, the most massive black hole merger had a much smaller total mass of 140 times that of the sun.

The researchers even theorized that the two black holes could have formed through earlier mergers of even smaller black holes.

The discovery “marks a landmark achievement in gravitational-wave science,” Amit Singh Ubhi, a research fellow at the University of Birmingham and a member of the LVK Collaboration, said in a statement. “It opens a new frontier in our understanding of black hole formation and underlines the urge to accelerate innovation towards the next generation of gravitational-wave detectors.”

LIGO forms international collaboration to find gravitational waves

Funded by the National Science Foundation, LIGO (the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory) previously made history in 2015 when it made the first-ever detection of gravitational waves. The space-time ripples were discovered by LIGO’s twin detectors in Livingston, Louisiana, and Hanford, Washington.

In the years since, LIGO joined forces with gravitational wave detectors Virgo in Italy and the Kamioka Gravitational Wave Detector (KAGRA) in Japan. The collaboration has fueled the discovery of more than 300 black hole mergers during surveillance of the Milk Way galaxy.

Researchers still have work ahead to refine the analysis of the recent black hole merger and improve stellar evolution models, Gregorio Carullo, a Birmingham professor who helped analyze the findings, said in a statement.

“It will take years for the community to fully unravel this intricate signal pattern and all its implications,” Carullo said. “There are exciting times ahead.”

Eric Lagatta is the Space Connect reporter for the USA TODAY Network. Reach him at elagatta@gannett.com

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Largest black hole merger ever detected through gravitational waves