I am the current Fulbright Professor of International Affairs at the Diplomatic Academy of Vienna, Austria. Students from here have staffed the world’s embassies and foreign offices since 1754. An American has held this seat since 2001. I appear to be the last.

To date, no replacement has been announced, nearly six months behind the normal timeline. President Donald Trump’s administration has delayed, and then rescinded, the appointments of more than 200 American scholars to this and other educational institutions.

Those delays should trouble any American committed to a free society, particularly conservatives given that brand’s longstanding fear of government overreach into the free marketplace of ideas. Scholars had previously been chosen on academic and classroom merit, regardless of their ideological compatibility with the current government in power.

As a historian I am obliged to stress the word “current” in that sentence. Nonpartisan oversight of public institutions ensures a wide variety of views and the exclusion of none. Conservatives are right to fear government oversight of ideas. Once initiated, the muzzling of thought rarely recedes, and quite often consumes its own.

Opinion

But this is not an essay bemoaning the politicization of the classroom. It is about the widespread forgetting that poses the greatest current threat to our nation’s long-term peace and prosperity, including why institutions like the Fulbright Commission were established in the first place.

That was because of war. And in hope of doing anything possible to prevent its reprise.

The postwar world we’re enjoying

More than 70 million people died in World War II. More civilians than combatants. Hundreds of millions were displaced and homeless. Cities were crushed. Economies crumbled. And the world was given a new, inconceivably awful definition of the word “holocaust.”

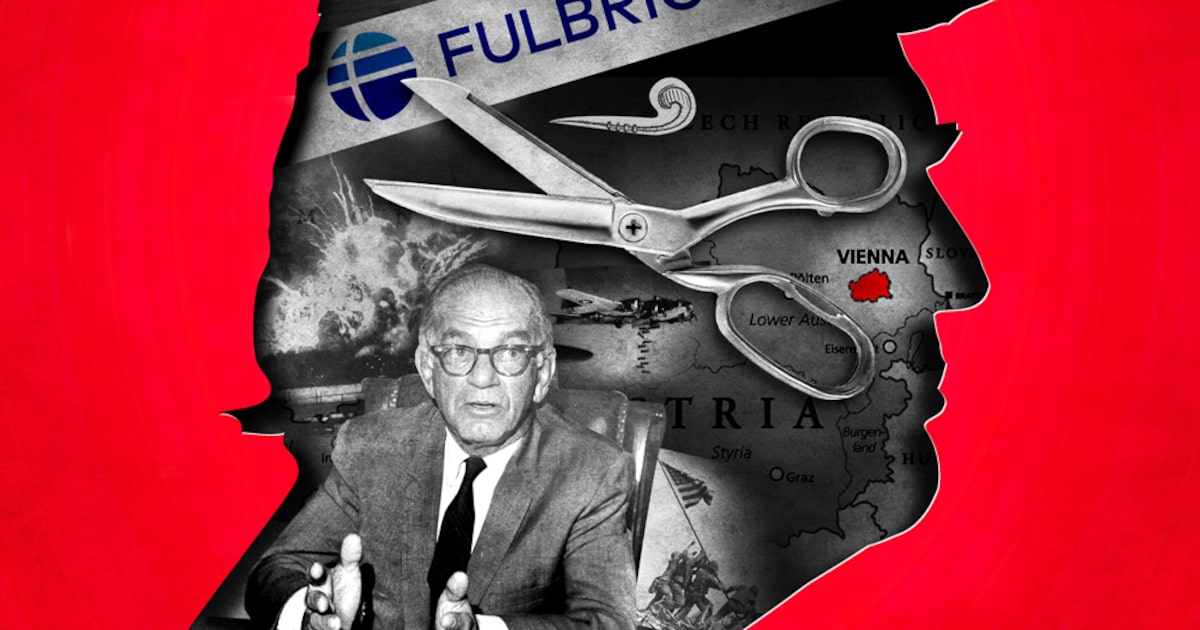

Arkansas Sen. William J. Fulbright was part of a generation that witnessed two global conflagrations. Leaders from that generation orchestrated the post-1945 world to avoid a third, including basic diplomatic, economic, educational and security structures.

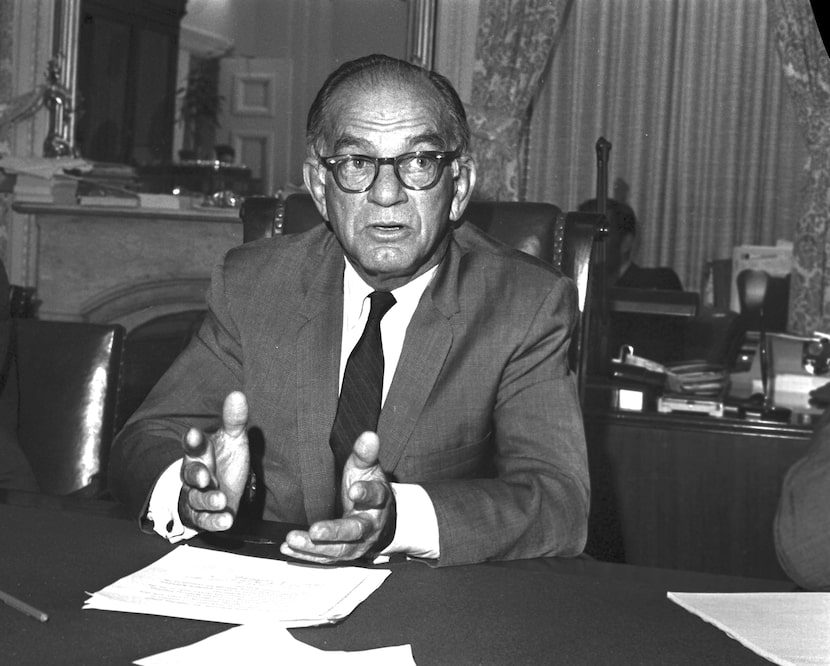

Senator J. William Fulbright (D-Ark.), chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, announces to newsmen at the Capitol that he plans to name a joint committee to examine secret Pentagon papers on the Vietnam war, June 23, 1971. (AP Photo/Henry Griffin)(HENRY GRIFFIN / ASSOCIATED PRESS)

Senator J. William Fulbright (D-Ark.), chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, announces to newsmen at the Capitol that he plans to name a joint committee to examine secret Pentagon papers on the Vietnam war, June 23, 1971. (AP Photo/Henry Griffin)(HENRY GRIFFIN / ASSOCIATED PRESS)

We have lived in the world they built ever since, at times uncomfortably and not infrequently in moments of genuine crisis, but also with a consistent baseline of stability few who lived through the first half of the 20th century could possibly have expected.

This world didn’t just happen. It was forged because successive generations of American policymakers had all internalized one basic lesson: The world is too dangerous to be left on its own, and too unsteady to long survive without calm and consistent American leadership.

Neither could it be ruled by force. With most of the world’s gold reserves and half its overall production, our predecessors could have bullied adversaries and allies alike to maximize American wealth, especially during our immediate post-war atomic monopoly. But the generation that had seen war with their own eyes chose long-term stability and expanding prosperity over short-term exploitation.

Their choice wasn’t out of goodwill alone, but for their own survival, and for ours. They did everything possible to build networks like the Fulbright Fellowships as well as other political ties, economic partnerships and educational exchanges, hoping and praying that by weaving a tight enough web of connections they might enable future generations to avoid relearning their most hard-won lesson the hardest possible way.

ORG XMIT: *S0420742733* From Wikipedia General of the Army George Catlett Marshall, Jr. GCB (December 31, 1880 – October 16, 1959) was an American military leader, Secretary of State, and the third Secretary of Defense. Once noted as the “organizer of victory” by Winston Churchill for his leadership of the Allied victory in World War II, Marshall supervised the U.S. Army during the war and was the chief military advisor to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. As Secretary of State he gave his name to the Marshall Plan, for which he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1953.(George C. Marshall Resarch Lib. / George C. Marshall Resarch Lib.)

Americans thus stayed and engaged overseas as never before after 1945. It wasn’t always pretty, efficient or even at times fully honorable. Military and economic conflicts, expansion of an expensive Cold War security architecture, and a long-term cantonment in Europe and elsewhere were hardly cost-free. But their price was by any reasonable measure less than the cost of war. More than 400,000 Americans lost their lives in World War II. Fewer than a quarter of that number have fallen in all our conflicts since. Each loss is a tragedy. Each sacrifice nearly too much to bear. But since 1945, American-built institutions, and American overseas engagement, has kept the catastrophe of global war at bay.

The investments we’re losing

Here was Sen. Fulbright’s open secret: Building, even over the long term, is cheaper than fighting. Case in point: Americans spent $4.6 trillion to win World War II and afterward helped fund Europe’s post-1945 reconstruction through aid programs such as the famed Marshall Plan at a cost of $13 billion in aid. That is approximately $150 billion in today’s dollars, spent to rebuild our most valuable trading and security partners for generations to come.

President Donald Trump leaves the podium after speaking in the Diplomatic Reception Room of the White House.(Pablo Martinez Monsivais / The Associated Press)

President Donald Trump leaves the podium after speaking in the Diplomatic Reception Room of the White House.(Pablo Martinez Monsivais / The Associated Press)

We spent $2.3 trillion fighting in Afghanistan between 2001 and 2022. That number exceeds last year’s federal deficit of $1.7 trillion, of which the Fulbright Program’s $288 million price tag contributes less than 0.02%.

One investment clearly paid better dividends than the other. I can visit Berlin and Rome today. I can even teach in Vienna, capital of the nation that joined with Nazi Germany in 1938. I have no expectation of ever seeing Kabul.

Smart spending was Fulbright’s entire post-1945 program of educational exchange. The goal wasn’t merely learning or teaching. Americans were to promote “a new manner of thinking about how to avoid war rather than wage it,” Fulbright argued, believing peace would be more easily maintained if more people, in every country, knew each other, and if more of the world’s students knew Americans especially, learning from them in classrooms and seminars before venturing off to their lives and careers.

Of course, educational exchanges alone would not maintain peace. Fulbright wasn’t so naive. Education could nonetheless play a remarkably affordable role within the overall national mission to reduce the causes of future conflict.

“The exchange program is not a panacea but an avenue of hope,” Fulbright explained. “Possibly our best hope and conceivably our only hope for the survival and further progress of humanity.” It wasn’t charity so much as insurance.

“If there is any reason for doing this,” he said, “it is for our national self-interest. We have more to lose from chaos and more to gain from the pursuits of peace than any other people.” Chaos, his generation had learned the hardest way possible, was best kept at bay.

The history we’re forgetting

This is the truly frightening aspect of the current administration’s decision to curtail and perhaps even one day end such exchange programs as the Fulbright. These and other elements of the oft-termed though short-lived American Century, including security pacts like the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, free trade as a bulwark of peace, and respect for American scientific, educational and engineering standards as the world’s ideals, are now disparaged by an administration that fundamentally questions their worth in a manner unseen since the 1930s, back when U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull warned that “If good can’t cross borders, tanks will.”

Secretary of State Cordell Hull sits at his desk, c. 1940. Hull served in the cabinet of President Franklin Roosevelt. (Library of Congress/MCT)(Handout / MCT)

The longest-serving chief diplomat in American history was, in time, proved right. But why, then, has the current crop of American leaders forgotten history’s hard-won lessons?

Perhaps because they, like most of us, thank goodness, having never witnessed the horror of a broken society, cannot fully appreciate its cost. The generation of Americans who remember real chaos is rapidly dwindling. More than 16 million Americans served in uniform during World War II. Only about 66,000 of them remain alive today. Nearly 1,000 pass on every week. With them goes the last firsthand knowledge of just how bad a world can get, leaving us with leaders wholly unaware of, and largely uninterested in, what previous generations suffered for our security.

Historians have seen this before. Four generations separate the end of the Napoleonic Wars and the start of World War I. Enough time for leaders to forget. Four generations now separate our own day from the bloodshed and hard-won triumph of World War II.

Historians like me can tell our fellow citizens why leaders like Fulbright believed it necessary to invest in peace. We cannot, however, prevent them from choosing policies more likely to incubate conflict. Neither can we teach the world’s next generation of diplomats what Americans built for their benefit if kept out of their classrooms.

Every Fulbright relationship and award is different. American taxes paid only $500 for me to teach American history and diplomacy in Europe. The Austrian Fulbright Commission and the Diplomatische Akademie picked up the rest, because they want to ensure their students, and the next generation of international diplomats and global leaders, hear an American voice in their curriculum. Perhaps they remember something too many current American policymakers have forgotten.

The reminder we need

My family fled Eastern Europe early in the 20th century. America took them in when other nations wouldn’t. We, in return, served, taught, healed, built and even paid the ultimate sacrifice in its defense.

And now I have returned to Europe on America’s behalf, not in spite of but because of this continent’s omnipresent ghosts. Outside my apartment building lies a brass marker noting that 63 of its residents spent their last days huddled within, awaiting their deportation to concentration camps from which few returned. People killed because they were like me.

Similar brass reminders front every address along my daily commute to work with the next generation of diplomats. I see the evidence of forgetting every time I leave for class, hoping to do some small part to ensure such hard-won lessons are never forgotten. That is why curtailing programs like the Fulbright exchange matters.

I write this from my last week in Vienna, 75 years after the first American Fulbright scholar taught in Austria, perhaps the last such American given the opportunity to play a tiny role in fulfilling Fulbright’s hope that we can learn from pain without experiencing it ourselves. I write to remind our current leaders, and my fellow citizens, that forgetting history’s lessons invites learning them anew.

Jeffrey A. Engel is the David Gergen Director of the Center for Presidential History at Southern Methodist University. He served as the 2024–25 Fulbright-Diplomatic Academy Visiting Professor of International Studies. The views expressed here are his and do not necessarily reflect those of his employers, the U.S. Department of State or the Austrian Fulbright Commission.