Editor’s Note: This story is part of Peak, The Athletic’s desk covering leadership, personal development and success through the lens of sports. Follow Peak here.

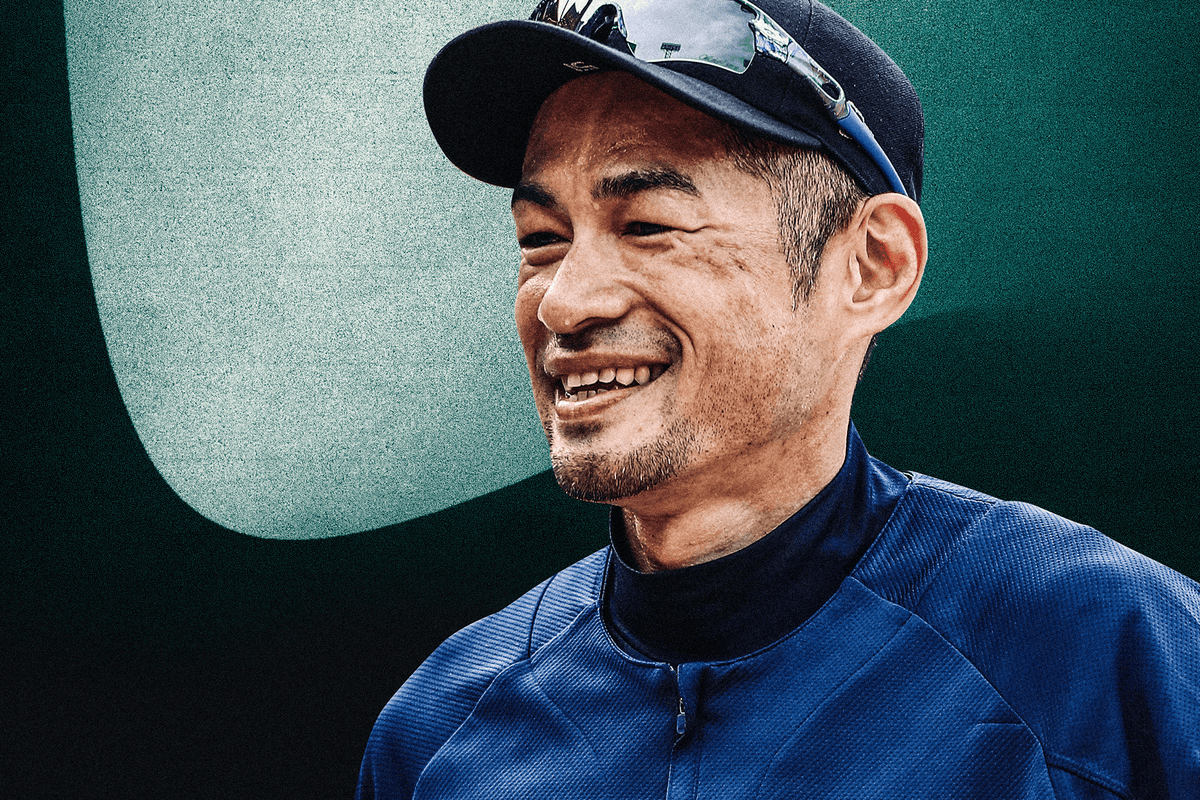

When Ichiro Suzuki is inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame on Sunday, it will culminate one of the most trailblazing and fascinating careers in Major League Baseball.

In 2001, Suzuki, a wispy, elegant right fielder from the Orix Blue Wave, joined the Seattle Mariners, becoming the first Japanese-born position player in MLB history. He promptly won AL MVP and rookie of the year in his first season, helping the Mariners win 116 games. Nineteen years later, he finished his career with 3,089 hits, playing his last game at the age of 45.

The numbers and accolades are only part of what made him an iconoclast. His devotion to his craft, idiosyncratic methods and dry sense of humor made him a beloved and transformational figure, a rare baseball player known solely by his first name: Ichiro.

In honor of his Hall of Fame induction, we went through the archives to find our four favorite lessons from his career.

1. Craft a routine, then follow it

One of the first things Ichiro did each day at the ballpark was weigh himself.

“He’s the only player I ever had,” said Rick Griffin, the Mariners’ former head trainer, “that weighed the exact same, to the ounce, at the beginning of the season and at the end of the season.”

The Mariners used to measure players’ body fat four times per year; Ichiro’s, like clockwork, was always the same.

“If he weighed 171.8 then he would eat a little more so the next day he would come in and weigh 172,” Griffin said. “If he weighed 172.3, then the next day he would eat a little bit less so he would weigh 172. He did that the whole time. It was unbelievable.”

Fastidious and regimented, he distilled his day into a collection of component parts, then repeated the same cycle. Every day, he walked into the trainers’ room at exactly 6:10 p.m., laid on the table and let Griffin adjust his hips and back. When the session finished, Ichiro nodded at Griffin and walked out of the room.

After batting practice, he always ate seven chicken wings, prepared by Mariners team chef Jeremy Bryant. Earlier in his career, it was nine wings.

“He came in one year and said, ‘Chef J, I’m gaining weight, so I can only have seven wings,’” Bryant recalled.

Sometimes Ichiro’s routine seemed curious. When he arrived in Seattle in the early 2000s, he kept his bats in a humidor, wiping them down after each game. On the road, he always had California Pizza Kitchen for lunch. Before day games, he skipped the wings and ate two corndogs, the cheap Costco kind. Echoing the English poet John Dryden, first Ichiro made his habits, and then his habits made him.

“If it was a 7 p.m. game, he’d be there at noon,” former Mariners general manager Bill Bavasi said. “And it wasn’t to play cards. He started preparing for a game when the previous game was over.”

2. Take your job seriously — but not yourself

You’ve maybe heard the Derek Jeter story. It happened while Ichiro was playing for the Yankees from 2012 to 2014.

Jeter was the unquestioned leader in the Yankees clubhouse, a quiet force who led by actions and presence. The last thing anyone wanted was to mess with the king. That didn’t stop people from joking about it, though.

“The joke was always to get someone to call Derek Jeter by his middle name: Sanderson,” recalled former Yankees pitcher Shawn Kelley. “People joked and snickered, but nobody would do it.”

One day, the Yankees were in a smaller clubhouse on the road. Jeter waltzed in during the afternoon. Moments later, Ichiro appeared.

“Sanderson!”

“Of course, everybody’s laughing and it’s funny and Jeter just gives him the death stare and makes a little joke back,” Kelley said. “But the funniest part is, Ichiro never sits still; he’s always moving. He’s either stretching or going somewhere, or he’s working on something or studying film. You’ll never see Ichiro just sitting there, but he sat there for minutes at his locker with his head down, just giggling. People were belly laughing — not at the fact that Ichiro did it, but the fact that Ichiro thought it was so funny.”

Ichiro liked to refer to Jeter as his “brother from another mother.” He sometimes called an umpire “home slice.” He rarely spoke English in public, which allowed him to weaponize the language for comedic effect. During his rookie season in Seattle, he told Mike Sweeney, then with the Royals, that he had a “nice ass.” He wrestled with Ken Griffey Jr. Once, he received a text from a particularly famous NFL quarterback, then wandered over to the Mariners coaching staff, looking for help.

“Who the f— is Tom Brady?”

And then there was the time Ichiro homered off Yankees closer Mariano Rivera in Seattle.

“He’s rounding the bases, and as he’s running home, he stops about 10 feet short of home plate, jumps, does the ‘suck it’ sign and yells, ‘Suck it!’” former Mariners pitcher David Aardsma said. “And then (he) touches home plate.”

Ichiro Suzuki was meticulous in his preparation and discipline, but he also liked to dine and joke around with his teammates. (Darren Yamashita / USA Today Sports via Imagn Images)3. Be open to outsiders, then dine with them

One day years ago, when former Rangers pitcher C.J. Wilson lived in Texas, he visited one of his favorite restaurants, Mr. Sushi.

The staff had a surprising message: Ichiro was there.

Wilson didn’t know him well, but sensed an opportunity. He asked the staff to pass along a message: Could he sit with him? He loved Ichiro!

Which is how Wilson came to spend a meal watching Ichiro down what felt like 70 pieces of sushi as they discussed their shared love of Porsches.

For teammates of Ichiro, it was a common ritual. It wasn’t always easy to get to know the man behind the routine, but Ichiro seemed to take great pleasure in the simple act of dining with friends.

He once hosted Sweeney and his wife Chara for a home-cooked meal in Seattle. He told his guests he wanted to play until he was 50. Sweeney believed him.

One night in Atlanta, during a quiet moment in the season, Mariners pitcher Ryan Rowland-Smith approached Ichiro’s interpreter Ken Barron and asked if he and Ichiro wanted to join him at Applebee’s that night.

“I was just joking about Applebee’s,” Rowland-Smith said, “but I wanted to have dinner with him, but figured there was no way it’d happen.”

After the game, Ichiro found Rowland-Smith and invited him to dinner at a Japanese restaurant. The restaurant was cleared out; the staff lined up as they entered. For two and a half hours, they sat and ate and shared stories about baseball and their lives.

“It was one of the coolest off-the-field moments I’ve ever had,” Rowland-Smith said.

Ichiro had a knack for making connections. In the early 2000s, he befriended Buck O’Neil, the Negro Leagues legend and founder of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City. Often, he showed up at the museum on his own. He loved the stories.

“When Buck died in 2006, Ichiro sent flowers,” said Bob Kendrick, president of the museum.

In the latter stages of his career, his penchant for entertaining teammates did not cease. One night in Philadelphia, when Ichiro was playing for the Miami Marlins, he invited Dee Strange-Gordon to come out for a meal.

It was past 10:30, and Gordon knew that most places had to be closed, but Ichiro told him not to worry.

“Yeah, Dee, we’re still going to dinner,” he said.

Sure enough, they showed up, and another restaurant was cleared out, set up for Ichiro and a friend to share a meal.

4. Be detailed. Respect your craft

Ichiro always displayed sincere reverence for his equipment. His glove always sat in the same spot. His bats were sorted, organized, polished and leaned just so.

It was the exact opposite of Mariners second baseman Bret Boone, who used to return to the dugout after a half inning and toss his glove to the side. One day, Ichiro watched Boone do this and provided a frank observation:

“Boone,” Ichiro said, “you do not respect your equipment.”

Ichiro’s bats were not just tools; they were an extension of himself, ordered and pristine.

“They were nice and neat, and they got respected and they were never slammed,” recalled former teammate Randy Winn. “They were never thrown. You know, now that I’m thinking about it, when he hit, he may have laid the bat down gently. I’ve actually never seen his bat laying in the dirt.”

Once, Ichiro was playing with Eduardo Perez, who found himself in a slump and — in a moment of desperation — did the unthinkable: He went and grabbed one of Ichiro’s bats and headed to the plate.

“Screw it, man,” Perez recalls thinking. “I’m going to take one of his bats.”

Perez walked to the plate, dug into the box and peered toward the dugout. Ichiro was in disbelief.

“His eyes opened as wide as I’d ever seen them,” Perez said. “He was so pissed off.”

Perez hit a pitch off the end of the bat. It trickled up the middle for a single. He pumped his fist all the way up the line.

When he returned to the dugout, Ichiro was waiting. He scribbled something on the bat, handed it to Perez and offered a begrudging sign of respect.

“Congratulations,” he said, and then walked off.

To Perez, it was pure Ichiro. He was one of the most eccentric players in the history of the game — talented, mesmerizing, focused and disciplined. There was only one Ichiro.

(Illustration: Dan Goldfarb / The Athletic; Omar Rawlings / Getty Images)