If you’re familiar with the island of Martha’s Vineyard, you might think of it first and foremost as a summer vacation destination for the wealthy and famous. You might know that it’s beloved for its beautiful beaches and quaint architecture. You might even have heard that it was named after a British explorer’s daughter.

But the island had a name long before British explorers “discovered” it — Noepe, or “a still place among the currents.” And it’s far more than just a tourist destination for the people who have called it home for centuries: the Aquinnah Wampanoag.

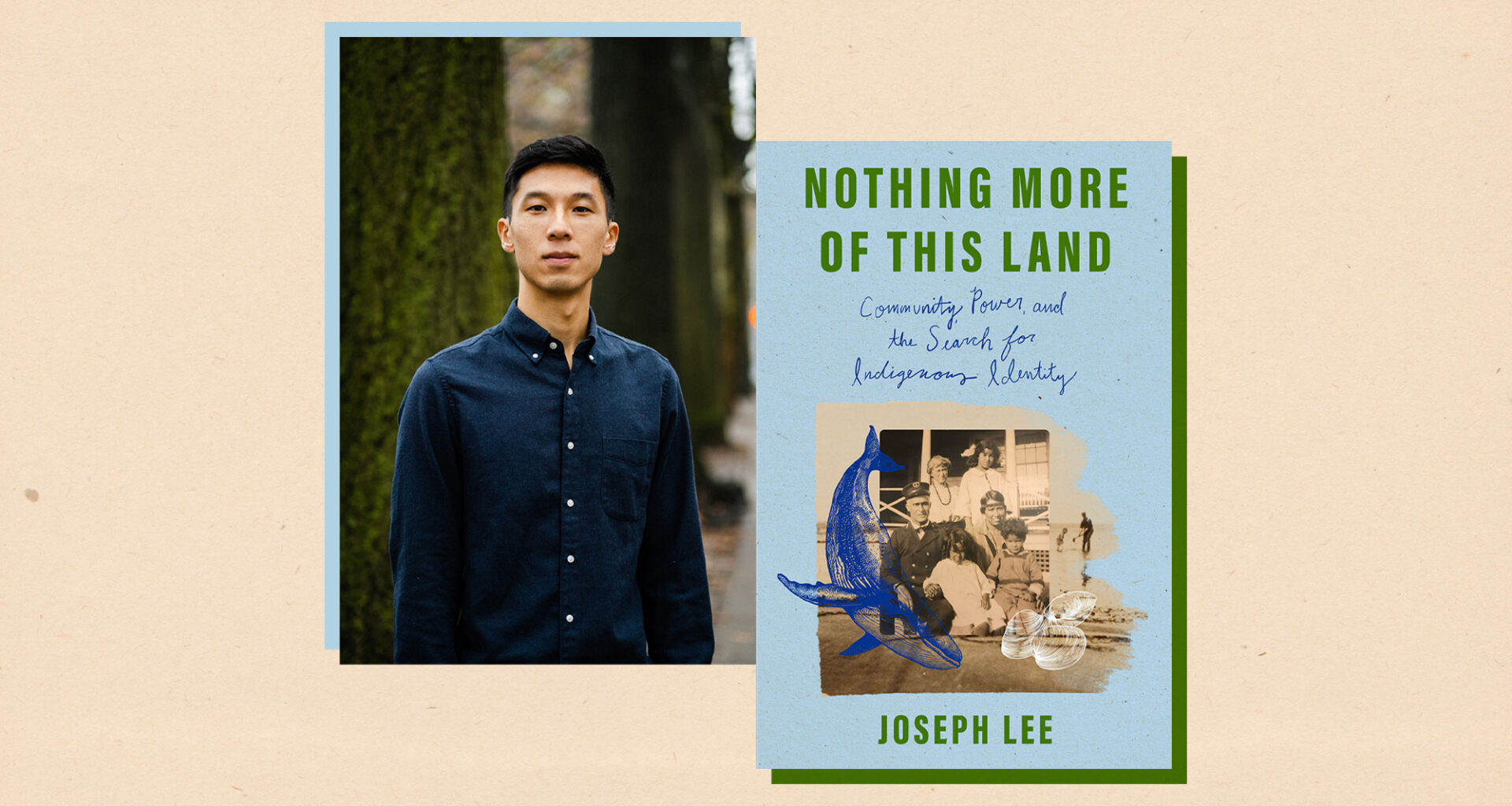

In his new book, Nothing More of This Land: Community, Power, and the Search for Indigenous Identity, Joseph Lee, a former Grist fellow and member of the Aquinnah Wampanoag tribe, uses his own experience as a jumping-off point to delve into the stories of Indigenous peoples all over the country, and the world. The book explores what it means to be Indigenous and how this identity is wrapped up in relationship to land.

For Lee, Martha’s Vineyard is both a homeland and a complicated source of identity — a place where he spent his summers attending a tribal camp, working in his family’s souvenir shop, and even participating in performances of Wampanoag legends for paying tourists. In the book, he discusses how he has grappled with colonialism and found ways to embrace his heritage, as he learned more about his own tribe and the stories of other tribes.

Lee discussed some of the book’s themes with Grist’s Anita Hofschneider, who hails from another often-misunderstood island: Guam. We’re sharing their Q&A in this week’s newsletter, which covers the tension that tourism and climate impacts bring to Indigenous land struggles, and why it’s important to grapple with the nuances of Indigenous identity — especially so in the era of climate change. Their interview was condensed and edited for clarity.

— Claire Elise Thompson

![]()

Rising seas, vanishing voices: An Indigenous story from Martha’s Vineyard

Anita Hofschneider: How would you describe the connection between Indigenous identity and climate change?

Joseph Lee: When you talk about Indigenous people, you have to talk about land. And right now, when you’re talking about land in any context, climate change is the looming backdrop. So many of the challenges Indigenous communities are facing may not be outwardly related to climate change, but they’re impacted by climate change. Fighting for water rights, which I would say is a sovereignty fight and a political fight, is made more difficult and the stakes are higher because of drought. Tensions around land ownership and what we do with our land are also made more complicated by climate impacts like rising sea levels and stronger storms that are eating away at our land. If you’re fighting over land and land you’re fighting over is shrinking because sea levels are rising, it makes that fight much more intense and much more urgent. You could look at salmon and the right to protect salmon and for subsistence lifestyles and all that’s becoming more complicated not just because of overfishing but because the way that salmon and other fish are impacted by warming waters and climate change. Any area of the story that you’re looking at, climate change is present.

AH: I also grew up on an island that is a tourism hub, and in so many communities that’s often perceived as the only viable economic driver. Can you talk about what it feels like to be Indigenous in a land that’s become a tourist destination, and how that affects our communities?

JL: In this country, one part of the experience of being Indigenous is the experience of erasure and of being ignored. That’s throughout history, through culture, through politics, through all these spaces. But I think especially in a place like Martha’s Vineyard, it’s even more extreme because the reputation of the place is so big and so specific. Being Indigenous, people are really often not listening to you. The more your land becomes a tourist destination, the harder it is for Indigenous voices to be heard, the harder it is for Indigenous people to hold onto the land.

In a very concrete way, tourism typically drives property values up. It drives taxes up. And that makes it harder for folks to hold on to land that’s been in the family for generations. And that’s what’s happened in Martha’s Vineyard. Beyond that, I think tourism is just a really, really difficult and unfortunate choice that people have been kind of forced into. When so much opportunity has been taken away or denied from Indigenous communities in these places, tourism is often the only thing that’s left. So it can become like a choice between having nothing and contributing to tourism, which is probably ultimately harming the community and the land, but there’s no other way to make a living. So I think that’s just a really unfortunate reality.

AH: There’s a part in the book where you’re talking about how every time you say you’re from Martha’s Vineyard, people either assume you’re really rich or they think, “Oh, I didn’t realize that people live there.” And that really resonated with me because when I say I’m from Saipan or Guam, people either don’t know what it is or they assume, “Oh, are you military?” And then when I say I’m not military, they are confused. This is a long way of asking, what do you want people to know about your community and your tribe in particular, separate from the broader journey of this book? Is there anything that you wish people knew that this book could convey so that other tribal members don’t have to be on the receiving end of that question?

JL: First, I hope that this will help to change the narrative of erasure that has existed about Wampanoag people for most of this country’s history. At the very least, I hope this helps people know that we exist — we’re here. And also, I like to think that it helps to show some of the complexity and diversity of my community: that we have disagreements, we have different perspectives, we have different talents, we live in different places.

Something else that your question made me think of was the question of audience. And I thought about that a lot. Even growing up within the tribe, there was so much just about my own community that I didn’t know. And so I try not to be judgmental of what people know, whether they’re Indigenous or not. And that’s how I really wanted to approach the book. I would hope that Indigenous and non-Indigenous readers can get something out of it, both in terms of learning things, but also hopefully seeing themselves in the pages and this exploration of figuring out who we are and where we want our community to go.

AH: Another part that really resonated with me and I think a lot of Indigenous readers will relate to is the struggle of what does it mean to be Indigenous if you aren’t living on your land. I was wondering what you hope Indigenous readers will take away from the book in terms of understanding what distance from their land can mean for their identity.

JL: I hope that Indigenous readers will discover what I’ve discovered, which is that there are so many ways to engage with your homelands and your home community, even if you don’t live there. I used to think that I was only engaging if I was there with the tribe doing some cultural tribal event or something, and I realized that there are so many other ways of engaging. I don’t think any of us are less Indigenous because we live somewhere else.

For a long time I felt like if it wasn’t perfect, it wasn’t worth it. If it wasn’t the perfect ideal of me participating in the tribe, I thought I shouldn’t do it. Ultimately what that led to is I just wasn’t doing anything because I didn’t have as many opportunities to go to these tribal gatherings or participate in tribal politics. And so I just did nothing, and I felt the distance sort of growing over the years. What other people can do is realize that there are all these small ways to engage and to try to embrace those, and not let ideas of what it means to be Indigenous be defined by outsiders, or these big colonial structures like federal recognition, for example, or blood quantum.

AH: Why? What’s at stake? Why do you think it’s important for folks to embrace Indigenous identity and why is it important, particularly at this moment?

JL: Circling back to what we talked about at the beginning, we’re not going to be able to address these huge existential crises like climate change if we can’t be at least in some way united as a community, as a people. If we’re always fighting over who belongs and what does it mean to be Indigenous and saying that people are less Indigenous because of XYZ, that takes away our ability to tackle those bigger challenges. Right now we’re facing these serious challenges and that’s what we should be dealing with, so figuring this out is the first step.

— Anita Hofschneider

More exposure

A parting shot

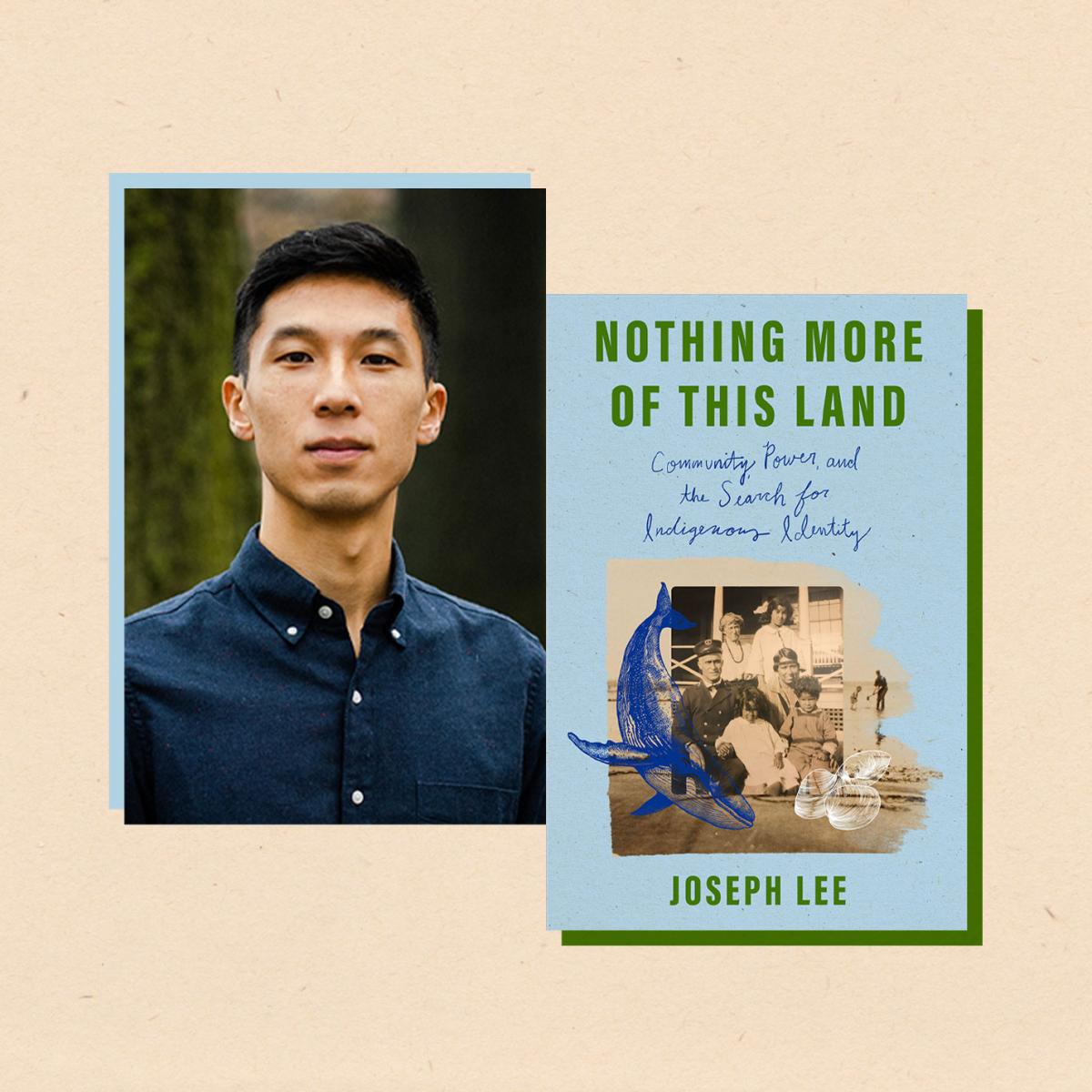

As part of his reporting for the book, Lee traveled to California and Oregon to meet with tribal members who were preparing for the largest dam removal in U.S.history — a major victory for the tribes’ fishing rights and the health of the land. “I had gone into the week thinking I was going to learn about sovereignty,” Lee writes, “and I definitely had, but I was also realizing all the different ways that Indigenous people had relationships with the land. Every relationship was unique and complex.”

Learn more about the decades-long battle behind the removal of the Klamath River dams in this epic feature by Anita Hofschneider and Jake Bittle. The photo below shows Leaf Hillman, one of the key removal advocates from the Karuk Tribe, embracing his family as they watch the deconstruction of the Iron Gate dam — the largest of the four dams on the Klamath River — last August.