Everyone agrees that diet is important to good health. And yet fewer than a third of medical students receive the recommended minimum of 25 hours of nutrition education, and more than half report receiving no formal education on the topic at all.

That’s why health secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. may be pushing on an open door with his plans to require medical schools to include nutrition education in their curricula or else lose federal funding.

“One of the things we’re gonna do at NIH is to really give a carrot and stick to medical schools across the country saying you gotta put in your first-year curriculum a really good, robust nutrition course,” he said in a video posted to his Instagram account earlier this month.

Medical experts who spoke with STAT noted that there is no standardized curriculum for nutrition, and that it’s not yet clear what specifics Kennedy may attach to funding or what training medical schools might have to cut back to make room for nutrition courses. But they were on board with Kennedy’s general goal, noting that many nutrition and food policy experts have been calling for this kind of change for years. A 2022 House of Representatives resolution on the need for better nutrition education also won bipartisan support. And some medical schools have already taken steps to strengthen their offerings on the subject.

“Nutrition is already robustly integrated (since 2019) into multiple required courses and clerkships in the four-year curriculum for Harvard medical students, providing them with repeated exposure to this critical topic,” Harvard Medical School told STAT in a statement. (The school also acknowledges there’s always room for improvement: “Nutrition just has not occupied enough of a space in our curriculum,” dean for medical education Bernard Chang told the university’s magazine last year.)

Beyond having students learn the ins and outs of nutrition itself, experts who spoke with STAT expressed hope that Kennedy’s push would be an opportunity for future physicians to learn something they say is even more crucial: how to talk to patients about their eating habits sensitively and without judgment.

“Of course there’s a need for increased training on nutrition; I think that’s very important,” said Rebecca Puhl, deputy director for the Rudd Center for Food Policy & Health at University of Connecticut, whose research focuses on weight bias. “But if there isn’t also training to ensure that those discussions with patients about weight-related health are respectful and supportive, it’s unlikely that any discussions are going to be productive or effective, and instead patients are gonna be left feeling blamed or shamed, not empowered.”

A better approach to talking about food with patients

Research shows that many medical professionals are biased against higher-weight patients — a finding that makes sense given the prevalence of weight stigma throughout U.S. society, Puhl said. “They are exposed to the same sociocultural values of thinness, so they’re not immune,” she said.

One study of patients with type 2 diabetes, for example, found that 44% reported feeling judged by their doctor because of their weight in the last 12 months. Not only can those negative experiences make patients feel upset and disrespected, research shows it makes them less likely to trust their providers and to seek out medical appointments down the line — meaning that, whatever a provider’s intentions, a brusque remark or carelessly phrased question can wind up driving patients further away from the care they need.

Puhl sees mandatory nutrition education as an opportunity to educate medical students about the complex factors — some of which are beyond an individual person’s control, like genetics and environment — that influence weight, so that they understand the common refrain to “eat less, exercise more” is far too reductive. She’d like to see physicians trained on how to actively listen to their patients when they describe their health issues and medical histories. Much of the time, patients have been trying to lose weight for years only to gain it back, leaving them frustrated and discouraged. (One meta-analysis found that patients typically regain half the weight they lose after two years and 80% of the weight they lose within five years.) “They don’t need to be told, you need to lose weight,” Puhl said.

Physicians should also learn to avoid making assumptions that body weight is the root of any problem a patient is experiencing, she said, and focus on metrics of health like mobility or cholesterol levels rather than body mass index, or BMI. The American Medical Association in 2023 recommended that doctors de-emphasize BMI as a measure of health, noting that the measurement was based largely on the bodies of white non-Hispanic people and doesn’t take into account variations according to factors like gender and ethnicity.

The most fundamental thing, Puhl said, is to teach medical students about “entering these conversations with compassion.”

Sign up for Morning Rounds

Understand how science, health policy, and medicine shape the world every day

The importance of educating future physicians about taking a compassionate approach to conversations about diet and health was also emphasized in a 2023 consensus statement from dozens of nutrition experts and residency program directors, published in the journal JAMA Network Open. Among the 36 core competencies the experts recommended were how to start a “sensitive, nonjudgmental conversation about food and lifestyle,” demonstrating “sensitivity to the social, cultural, emotional, economic, educational, and psychological factors that may affect an individual’s nutrition behavior, food choices, and health status,” and demonstrating “empathy and sensitivity when counseling patients with obesity and eating disorders.”

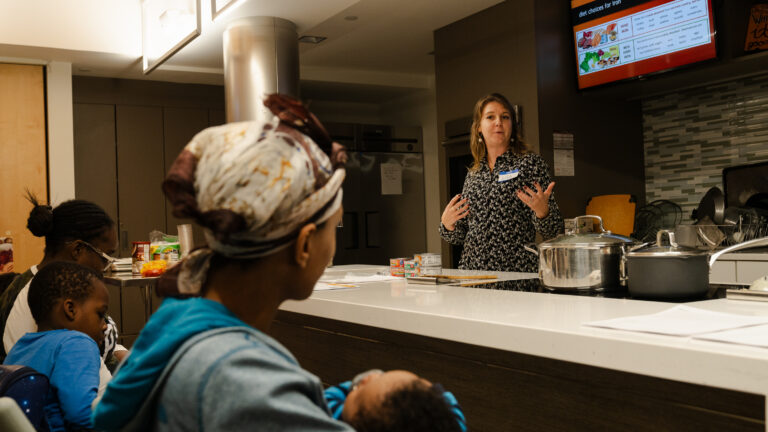

David Eisenberg, director of culinary nutrition at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, co-authored the consensus statement. As the founder of the movement to introduce teaching kitchens in hospitals, universities, and other settings where medical professionals and patients can learn how to cook nutritious meals, he’s an advocate for the importance of hands-on learning.

“Trying to teach patients, medical students or doctors about nutrition and better choices of food in the absence of some experiential learning in the kitchen is like talking to people about the benefits of swimming in the absence of a swimming pool,” he said. With teaching kitchens, “in as little as two hours, a physician who knows nothing about cooking and who is almost always intimidated by the notion of holding a chef’s knife that’s razor sharp and attacking an onion or a piece of chicken breast, they’re shown that they can do this.”

At least 34 medical schools in the U.S. teach culinary medicine, which Eisenberg says can make graduates both more confident and more practical in talking to patients about their diets. Hope Barkoukis, who chairs the nutrition department at Case Western Reserve University’s School of Medicine, developed a wellness and preventive care pathway program for medical students there that includes lessons on nutrition and culinary medicine. One clear change she’s seen in the medical students who go through the program: They embrace “the importance of focusing on telling patients what they CAN eat instead of what they can’t eat,” she said via email.

But in addition to the transformative power of learning how to make sheet-pan chicken or a vegetable-laden stirfry, getting an education in how to broach the topic of food with patients is also a topic near to Eisenberg’s heart.

“I’ve practiced primary care for well over a decade in the Harvard hospital system,” he said. “It’s an improvisational dance with a patient. One wrong statement or nonverbal glance at somebody when the topic of food comes up, and they will shut down.”

At a hospital’s teaching kitchen, patients get a taste of food as medicine

A 2023 paper he co-authored explored ethnographic approaches to opening up conversations about food in what he calls a “non-threatening and inviting” way, suggesting health care providers ask open-ended questions like “What is your approach to food?” and “Where do you want to take your relationship to food a year from now?”

As with taking a patient’s sexual history, Eisenberg said, food and its intersection with health and body shape and size is deeply personal. There are many examples in medicine, he said, “where it’s the skill of the inquiry and a lot of non-verbal communication that allows a patient to tell you the truth.”

Beyond nutrition education

For his part, Eisenberg does think future physicians should also be able to answer nutrition questions like which kinds of oils or proteins are healthiest and why, or “which micronutrients are essential for whom at what stage of life.”

“Right now, all we have is what minerals or supplements are missing in somebody that has scurvy” when it comes to the questions medical students face on exams, Eisenberg said. “It’s that level of crazy biochemistry that is irrelevant to day-to-day practice in America in 2025.”

Puhl also says there’s particular value in teaching medical students about nutrition given that “there is so much noise in the media about what it means to be on a diet, what it means to eat healthy, what it means to restrict certain foods.” Ongoing controversies and evolving research about everything from alcohol’s cancer risks to the saturated fat in dairy underscore the need for up-to-date education.

For Christina Roberto, director of the Center for Food and Nutrition Policy at the University of Pennsylvania, the main value of mandatory nutrition education lies in the opportunity to tackle the subject of weight bias and to help doctors understand why it’s important to refer certain people — a patient with type 2 diabetes or someone who’s taking a GLP-1 weight loss drug — to registered dieticians and nutritionists who can help them plan optimal diets for their specific situations.

STAT’s coverage of chronic health issues is supported by a grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies. Our financial supporters are not involved in any decisions about our journalism.