In the 1980s, when Ronald Reagan reduced the government’s role in health care, including cuts to Medicaid, Whatcom County responded. The federal budget cuts spawned the creation of Interfaith Family Health, which is now Unity Care NW, a health center for nearly 25,000 patients in Whatcom.

With the Trump administration taking an axe to health care funding through the passage of the “big bill” on July 4, some local health care leaders see an opportunity like that of the ‘80s.

Others, like Gov. Bob Ferguson, say Washington’s health care system will be brought to the brink because of sweeping cuts to Medicaid. To run Apple Health, Washington’s Medicaid program, the state receives about $13 billion annually in federal dollars, the largest share of federal funding the state receives. One-fifth of those federal funds — $3 billion to $5 billion — are now at risk. Washington state will endure nearly $37 billion in federal Medicaid cuts in the next 10 years, according to Congress’s nonpartisan scorekeeper.

The uninsured rate of Washingtonians is likely to more than double from nearly 5% in 2023 due to the legislation, Ferguson said.

In Washington’s 2nd Congressional District, which comprises parts of Snohomish, Skagit and Whatcom counties and all of Island and San Juan counties, 34,000 people with health insurance through the Affordable Care Act will see premiums jump by an average of $1,460 a year with 186,000 people at risk of losing Medicaid, according to the district’s Rep. Rick Larsen.

While new Medicaid work requirements, cuts to nutrition programs and impacts on medical providers aren’t set to be felt for at least a year, nearly 80,000 Washingtonians are at risk of losing health insurance if Congress allows Biden-era premium subsidies to expire on Dec. 31, 2025. Because of this potential fallout, health insurers have requested a 21.2% average rate change for Washington state’s 2026 Individual Health Insurance Market, which the state’s Insurance Commissioner is currently considering.

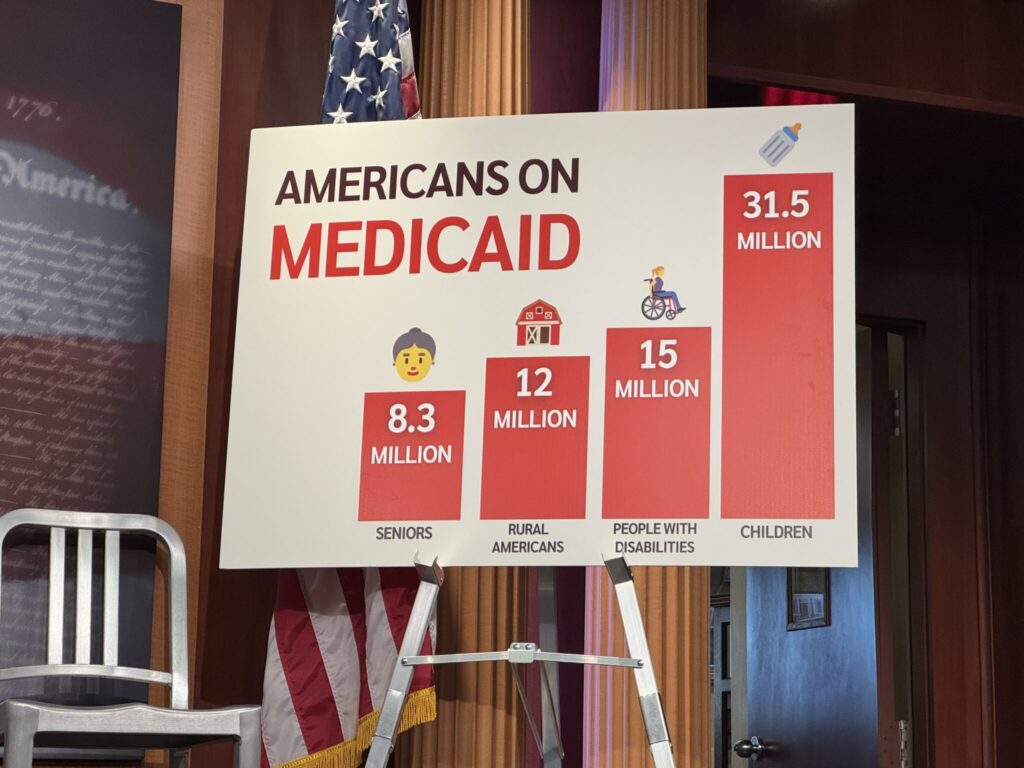

Medicaid sign at U.S. Senate Democrats’ press conference in February. (Photo courtesy of Shauneen Miranda/States Newsroom)

Medicaid sign at U.S. Senate Democrats’ press conference in February. (Photo courtesy of Shauneen Miranda/States Newsroom)

Changes to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) — of which nearly 25,000 Whatcom residents use — including new work requirements, are already in effect but have yet to be rolled out by states awaiting federal guidance. Beginning Oct. 1, 2026, Washington must cover 25% more of SNAP costs that the federal government will no longer support.

With varying shares of Medicaid patients, local health providers are bracing for trickle-down impacts that remain cloaked in unknowns, delays and possible claw-backs.

PeaceHealth

PeaceHealth St. Joseph, Whatcom County’s only hospital, is expecting the megabill to result in more emergency department visits, particularly from uninsured people seeking primary care, according to Rep. Larsen, who met with PeaceHealth this month.

Nearly 20% of the hospital’s patients are covered by Medicaid, PeaceHealth’s spokesperson Amy Drury said.

“PeaceHealth is committed to ensuring that all we serve have access to the very best health care services, regardless of their ability to pay,” Drury said in a statement to CDN.

The PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center emergency entrance. The hospital did not say whether it anticipates staff cuts due to the “big bill.” (Hailey Hoffman/Cascadia Daily News)

The PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center emergency entrance. The hospital did not say whether it anticipates staff cuts due to the “big bill.” (Hailey Hoffman/Cascadia Daily News)

Regardless of the hit PeaceHealth takes, the organization can do what American healthcare is good at: shift costs around to offset losses by increasing revenues elsewhere, all while attempting to endure minimal damage in the process, according to Dr. Marc Pierson, a former PeaceHealth executive. While a possibility, this raises the question of what hit PeaceHealth would have to take, possibly including but not limited to layoffs and service cuts, said Zach Levinson, the project director of the Project on Hospital Costs at KFF, an independent health policy research organization.

Drury did not specify in a statement to CDN whether the hospital, which saw network-wide layoffs in May, expects staff reductions due to funding changes, adding that the hospital seeks to avoid impacts to caregivers.

Pierson, who says low- or non-profitable programs could be cut, also anticipates that it’ll become harder for lower-income people, who will have to wait longer, to access care.

The megabill included a $50 billion rural health fund, half of which will be distributed to states. Urban-based hospitals such as PeaceHealth that serve a notable rural population could receive some of the funds from the state, though it remains unclear how states will distribute the yet-to-be-determined amounts, Levinson said.

Skagit Regional Health

Skagit Regional Health, which operates two hospitals and nearly two dozen clinics, received $90 million in Medicaid payments in 2024. Medicaid makes up about 17% of the network’s total revenue.

Tens of millions of dollars in losses are at stake for Skagit Regional, spokesperson Lourdes Edralin told CDN in a statement.

To offset the losses, the safety net health system hopes to raise its operating income by $25 million next year. Women’s health, in-patient mental health and children’s therapy stand to be impacted greatest as a larger share of patients, 72%, 56% and 65%, respectively, use Medicaid.

The health system has “no plans for immediate across-the-board staff reductions,” Edralin said, adding that they’ll take a selective approach to rehiring vacated positions.

Family Care Network

With 15 clinics and urgent care centers in Whatcom and Skagit counties, Family Care Network, an independent health care network, serves about 105,000 patients. Although nearly 14% of the network’s patients are on Medicaid, they’re not expecting any service reductions, layoffs or closure of clinics, a spokesperson told CDN.

Planned Parenthood

Protesters wield Planned Parenthood signs at a rally outside the Whatcom County Courthouse in May 2022 following the repeal of Roe v. Wade. Three years later, health care faces a different challenge in funding cuts, but Planned Parenthood does not expect service cuts as a result. (Hailey Hoffman/Cascadia Daily News)

Protesters wield Planned Parenthood signs at a rally outside the Whatcom County Courthouse in May 2022 following the repeal of Roe v. Wade. Three years later, health care faces a different challenge in funding cuts, but Planned Parenthood does not expect service cuts as a result. (Hailey Hoffman/Cascadia Daily News)

Planned Parenthood expects no service cuts at its locations in Bellingham, Mount Vernon or Friday Harbor. The three locations provided reproductive health services and other health care to 8,200 patients in 2024.

As of April 1, Mt. Baker Planned Parenthood’s three locations merged into Planned Parenthood of Greater Washington and North Idaho (PPGWNI). Nearly 50% of those patients use Medicaid, meaning roughly 30% of its revenue comes from Medicaid, according to Eowyn Savela, Vice President of Public Affairs for PPGWNI.

Unity Care NW

In addition to Sea Mar — which did not respond to requests for comment — Unity Care NW is the only Federally Qualified Community Health Center (FQHC) in Whatcom County, meaning it guarantees care regardless of income or insurance.

The network is not expecting any service or staff cuts across its services, from medical and dental to pharmacy and behavioral health. Rather, Unity Care expects to have to do more with less, CEO Jodi Joyce told CDN. With nearly two-thirds of their patients on Medicaid, Unity Care will continue to serve anyone.

Joyce — who is hopeful this moment of threats to health care could spark an ‘80s-era opportunity — said she expects the network’s demand to rise and is even considering repurposing an outreach team that helped sign up patients for health insurance following the passage of the ACA to now help patients complete looming work requirements.

Owen Racer is a Report for America corps member who covers health care and public health in Whatcom and Skagit counties. Reach him at owenracer@cascadiadaily.com; 360-922-3090 ext. 101. Learn more and donate at cascadiadaily.com/rfa.