Emmett Till’s death shocked millions of people across America and was a catalyst for the Civil Rights Movement, but many facts about his life and his murder remained unknown for decades.

More than 60 years after his death in 1955, new reporting is re-igniting interest in Till’s case and spreading his story to a new generation.

NBC Chicago’s Marion Brooks started digging deeper into Till’s story in 2020, and her docuseries The Lost Story of Emmitt Till uncovered new details and cleared up misconceptions about Till’s life, death and legacy that continues today.

Emmett Till Almost Didn’t Go To Mississippi

Emmett Till had been to Mississippi earlier in his life, but almost didn’t make the trip in 1955. Emmett’s mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, was worried about Emmett traveling to the Jim Crow South. Brooks said Emmett Till had been surrounded by love and opportunity his whole life, and going to the south at that time set him up for a major culture shock that required learning the rules of life for African-Americans at that time.

“There was clear trepidation in the family about Emmett making that trip,” said Brooks. “No doubt his mother did not want him to go. In fact, she’d said no. He begged her and begged her and begged her. And he was an only child and got what he wanted quite a bit.”

Mamie eventually relented and allowed Emmett to go, something she would regret for the rest of her life.

“She tried to train him,” said Brooks. “The [family] all tried to tell him, you know, don’t get a wandering eye. Don’t look at anybody. Don’t look any white person directly in the eye. Say, ‘Yes, ma’am’ and ‘No, sir.’ And this is the way of the south.”

Till Inspired Federal Legislation to Ban Lynching

As defined by the NAACP, a lynching is “the public killing of an individual who has not received any due process.” In a page dedicated to the history of lynchings in the United States, the NAACP describes that lynchings “were violent public acts that white people used to terrorize and control Black people in the 19th and 20th centuries, particularly in the South. Lynchings typically evoke images of Black men and women hanging from trees, but they involved other extreme brutality, such as torture, mutilation, decapitation, and desecration. Some victims were burned alive.”

In 1900, the first legislation that would make lynchings a federal crime was introduced. It failed to pass. Despite numerous attempts in the subsequent decades, federal legislation that would make lynching a hate crime continued to stall.

“There had been almost 200 attempts to get that law passed, if not more,” Brooks said.

In 2022, a bill introduced by U.S. Rep. Bobby Rush of Illinois passed 422-3 in the House and unanimously in the Senate. It was signed by President Joe Biden into law.

The “Emmett Till Antilynching Act” made it possible to prosecute a crime as lynching when a conspiracy to commit a hate crime results in death or serious bodily injury, with a possible penalty of up to 30 years in prison, according to NBC News.

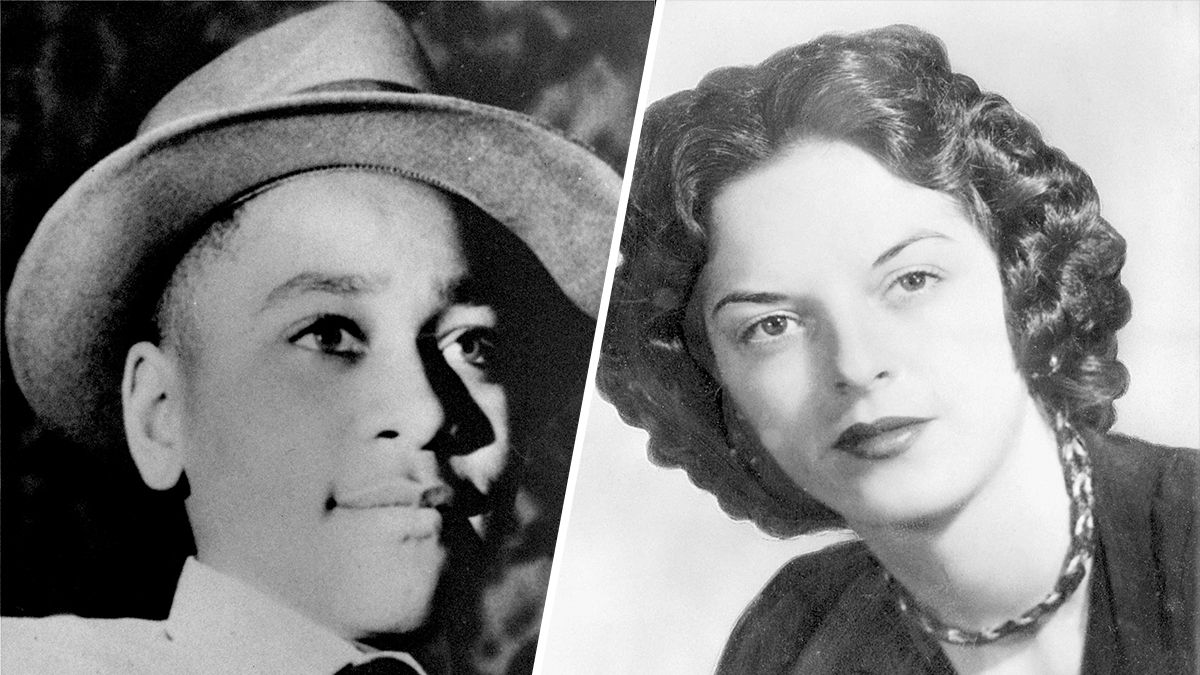

Emmitt Till Did Whistle at Carolyn Bryant

Debate swirled for decades over whether Emmett Till did, in fact, whistle at Carolyn Bryant outside of her grocery store on that summer day in 1955. Brooks, after speaking with multiple people present with Till that day, confirmed that he did.

“Emmett whistled,” said Brooks. “That is an account I heard from two cousins that were present. And as soon as that happened, everybody understood, this is bad. This is really bad.”

Brooks said Till was a jokester who liked to make people laugh and that he clearly did not know the racial and social dynamics of the Jim Crow South.

“People didn’t want to believe that he whistled,” said Brooks. “He, again, didn’t understand really where he was and the impact that would have. He had no clue, obviously, or he wouldn’t have done it… And what were his motivations at that moment? We’ll never know. And his friends, you know, his cousins were just petrified because they knew exactly what it meant. But he did, he did whistle.”

The 1963 March on Washington was held on the anniversary of Till’s death

Famous for being the setting of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom was held on Aug. 28, 1963. That year was the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation, but the specific date was picked to commemorate the eighth anniversary of Till’s death.

“[That] illustrates the intentional, direct correlation and to what effect that he had on the continuing movement in 1963,” said Brooks.

Brooks also shared that a previous biography of Mamie-Till Mobley by Christopher Benson revealed that, despite the date commemorating her son’s death, Till-Mobley didn’t attend the march because she didn’t think she was invited.

“She was invited to the March on Washington and never knew it,” Brooks said. “She didn’t realize she was even invited.”

Brooks said there was some disagreement and “drama” between the NAACP and Till-Mobley over a speaking tour she did after her son’s murder.

“It had been very difficult and very traumatic for her, of course,” said Brooks. “Bottom line is, she never knew. And the reason she didn’t know was her mother found the correspondence and hid it from her. She didn’t find out until years later. She thought she was forgotten. She thought she wasn’t included.”

The first jury vote for Till’s accused killers wasn’t unanimous

In 1955, JW Milam and Roy Bryant went on trial for Till’s murder and were acquitted by an all-white jury. Though they confessed to kidnapping Till, their acquittal on murder charges was broadly seen as a miscarriage of justice. Decades later, it was discovered that a few jurors initially voted to convict Milam and Bryant.

In 1962, a student named Steven Whitaker wrote his masters thesis about the Till case, and interviewed all 12 jurors. Whitaker was from Sumner, Mississippi, and knew many people involved in the trial. Brooks interviewed Whitaker for her 2020 docuseries.

“He interviewed the defense; he interviewed prosecutors; he interviewed everybody,” said Brooks. “One of the things that he did not write in his master’s thesis was after he talked to the jurors… three [jurors] told him that their first vote… was actually guilty. That was something we did not know.”