Overview of Key Changes and Immediate Impacts

Key Policy Shift: Section 330 Grants now treated as a “Federal Public Benefit”

- The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) now classifies the Health Center Program (Section 330 grants) as a “Federal public benefit,” which restricts Non-Qualified Aliens’ access to most services. Only emergency care, immunizations, and communicable disease treatment remain accessible to all.

Operational Conflict: Serving All Patients vs. Federal Eligibility Rules

- Community Health Centers and Federally-Qualified Health Centers (hereinafter referred to as “Health Centers”) must verify immigration status for federally funded services or risk non-compliance. Health Centers now have two conflicting mandates: Public Health Service Act Section 330 (obligation to serve all patients) vs. the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA) (restrict benefits to citizens and Qualified Aliens).

Effective Immediately: No Grace Period for Compliance

- The new policy is effective immediately, and there is no grace period for implementation. However, there is a 30-day comment period to challenge or seek clarification from HHS.

Critical Risks: Administrative Burdens and Uncompensated Care Costs

- New administrative burdens (such as screening and documentation) and uncompensated care costs may rise if Health Centers serve ineligible patients.

I. Background and Legal Context of PRWORA Reinterpretation

Background on PRWORA and the 1998 HHS Interpretation

The PRWORA, enacted as Public Law 104-193, established a comprehensive framework governing alien eligibility for various public benefits in the United States. Prior to the recent PRWORA notice (the “Notice”), UHHS had issued its interpretation of the term “Federal public benefit” in a 1998 notice (63 FR 41658, August 4, 1998). However, the Notice explicitly states that this previous interpretation “artificially and impermissibly constrains these statutory definitions.”

HHS’s Legal Justification: Rejecting the 1998 Framework

The Notice was published in the Federal Register (90 Fed. Reg. 41785 (July 14, 2025) represents a deliberate effort to revise the interpretation of “Federal public benefit.” This revision is predicated on a commitment to construing the “plain language” of 8 U.S.C. § 1611(c)(1)(A) and (c)(1)(B), asserting that the 1998 Notice was fundamentally flawed in at least four distinct ways.

HHS’s position is that the prior interpretation misconstrued the expansive scope of “any grant” and “eligibility unit” and failed to properly apply the “any other similar benefit” clause, thereby limiting the reach of PRWORA beyond Congress’s original intent.

The PRWORA’s stated purpose emphasizes that “aliens within the Nation’s borders should not depend on public resources to meet their needs” and that “the availability of public benefits should not constitute an incentive for immigration to the United States.” This national policy stance is further reinforced by recent Presidential actions, such as Exec. Order No. 14218, 90 Fed. Reg. 41210 (July 10, 2025)–“Ensuring the Integrity of Federal Public Benefit Programs which directs federal agencies to rigorously enforce eligibility requirements for public benefits, prioritizing access for U.S. citizens and Qualified Aliens, and mandates review of existing benefit programs for compliance with immigration-related restrictions.

Exec. Order No. 14159, 89 Fed. Reg. 18344 (March 4, 2024).–“Restoring the Rule of Law in Immigration Benefits Administration outlines the administration’s immigration policy framework, emphasizing lawful status as a condition for public benefit eligibility and instructing agencies to limit incentives that could attract unauthorized immigration.

II. Health Centers’ Mission vs. New Federal Restrictions

Health Centers are defined as community-based and patient-directed primary care practices strategically located in areas identified as having significant unmet healthcare needs. The Health Center Program is authorized under Section 330 of the Public Health Service Act (PHSA) (42 U.S.C. §254b) and is administered by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) within HHS.

HRSA awards grants to support outpatient primary care facilities, encompassing various types of health centers such as community health centers, health centers specifically for the homeless, those serving residents of public housing, and migrant health centers.

Mission at Risk: Federal Restrictions Clash with Safety-Net Mandate

A fundamental tension exists between the explicit mission of Health Centers and the implications of this reinterpretation. Health Centers are expressly designed as “safety net providers” to address the health problems of poor and underserved individuals, with a mandate to provide care “regardless of patients’ ability to pay”.

However, the new HHS reinterpretation directly challenges this principle by restricting access to federally funded services based on immigration status. This conflict will compel Health Centers to make difficult ethical and operational decisions, potentially leading to a significant re-evaluation of their service models and who they can effectively serve with federal resources.

III. New HHS Interpretation: Expanded Restrictions and Operational Challenges

Broadened Definitions: “Any Grant,” “Eligibility Unit,” and Catch-All Clause

In its July 14, 2025 notice (90 Fed. Reg. 41785), HHS issued a revised interpretation of the term “Federal public benefit” under the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA).

This reinterpretation substantially broadens the types of programs and services subject to alien eligibility restrictions. It explicitly overrules the narrower 1998 interpretation (63 Fed. Reg. 41658) and applies a plain-language approach to key statutory terms, notably “any grant,” “eligibility unit,” and “any other similar benefit” (8 U.S.C. § 1611(c)(1)).

1. Expansion of “Any Grant”

- The term “any grant” is now interpreted to include all forms of federal financial assistance, whether provided to individuals, nonprofit institutions, or state/local governments.

- This shift brings previously excluded funding mechanisms, such as Section 330 grants under the Health Center Program, squarely within the scope of PRWORA. As a result, all services delivered by health centers using Section 330 funding are now classified as Federal public benefits—services that may not be provided to non-qualified aliens unless a statutory exemption applies.

2. Broadening of “Eligibility Unit” and Catch-All Clause

- The Notice simplifies the definition of “eligibility unit” to include any individual or household to whom a benefit is delivered, eliminating the 1998 requirement for additional statutory eligibility criteria.

- The “any other similar benefit” clause is now read expansively to include any assistance that resembles the listed benefits (e.g., health, housing, food, education) in purpose or function. For health centers, this means that a wide array of direct patient services—if federally funded—are now subject to PRWORA’s immigration status limitations.

3. Explicit Inclusion of the Health Center Program

- Crucially, the Notice explicitly designates the Health Center Program as a provider of Federal public benefits.

- This marks the first time that Section 330 grant-supported services have been formally included in this classification. Unless an exemption applies, services funded by these grants must now be restricted to U.S. citizens and “qualified aliens” as defined in 8 U.S.C. § 1641.

Patient Care Disruptions: Eligibility Screening and Service Gaps

1. Restricted Services: What Non-Qualified Aliens Can (and Cannot) access

Health Centers must now assess patients’ immigration status before delivering most federally funded services. Non-qualified aliens—such as undocumented immigrants, DACA recipients without additional status, nonimmigrant visa holders, and individuals with Temporary Protected Status—are generally ineligible for services funded by Section 330 grants. Exceptions remain for a narrow set of services: emergency medical care, immunizations, and communicable disease testing and treatment (8 U.S.C. § 1611(b)(1)(C)).

In practice, this creates a service gap for non-qualified individuals seeking routine primary care, behavioral health, dental care, or preventive screenings—unless such services are paid for through non-federal funding sources (e.g., state, local, or private funds).

2. Documentation Requirements: Balancing Compliance and Patient Trust

The PRWORA requires providers of non-exempt federal public benefits to verify that an applicant is a “qualified alien.” However, the PRWORA also includes an exception for nonprofit charitable organizations, which are not required to determine, verify, or otherwise require proof of eligibility of any applicant for access to benefits.

Although the Notice does not revise formal verification requirements, it strongly encourages health centers to verify immigration status before delivering non-exempt services. HHS emphasizes that “nothing in the statute prohibits” verification and advises providers to “heed the clear expressions of national policy.”

Failure to verify status may expose centers to federal scrutiny, compliance risks, or financial clawbacks. Verification may include reviewing documents such as green cards (I-551), asylum approval notices, I-94 records, or work authorization under special immigrant categories. Importantly, health centers are not required to report undocumented patients to immigration authorities.

3. Workflow Overhaul: Intake, EHR Updates, and Staff Training

Implementing immigration-based service restrictions presents significant operational challenges. Health Centers must:

- Redesign patient intake workflows to assess immigration status while protecting patient privacy.

- Revise electronic health record (EHR) systems and billing platforms to tag services based on funding source and patient eligibility.

- Train staff on the new requirements, statutory exemptions, and culturally competent communication strategies.

- Segment care delivery—potentially within the same visit—when exempt and non-exempt services are requested simultaneously (e.g., immunizations alongside primary care).

Ethical Dilemma: Turn Patients Away or Absorb Unfunded Costs?

This reinterpretation places health centers in a difficult position: balancing their core mission to serve all patients regardless of ability to pay with the legal obligation to restrict federally funded services to eligible individuals. Centers must now decide whether to:

- Turn away ineligible patients—which may contradict state/local mandates or institutional values;

- Deliver care using non-federal funds, thereby absorbing additional uncompensated care costs;

- Or seek alternative funding mechanisms (e.g., California’s SB 75 and AB 133) to cover care for non-qualified populations.

In sum, the reinterpretation imposes immediate and far-reaching compliance obligations, forcing health centers to overhaul service delivery, eligibility screening, and funding allocation models while navigating ethical, legal, and operational challenges.

IV. Financial and Administrative Implications for Health Centers

Revenue Loss: Declining Visits from Immigrant Populations

- Health Centers serve a significant number of immigrant patients, particularly in underserved communities. Restricting services to Non-Qualified Aliens could reduce patient volume, as undocumented immigrants, or those unable to provide verification, may avoid seeking care due to fear of immigration consequences or inability to meet eligibility criteria.

- Reduced patient volume could impact the financial sustainability of Health Centers, as their funding models partly depend on patient service revenue and grant allocations based on service volume.

Stricter Oversight: Audits and Reporting for Section 330 Funds

- With the explicit designation of the “Health Center Program” as a “Federal public benefit,” Health Centers are now compelled to ensure that all services provided under these grants strictly comply with PRWORA’s alien eligibility restrictions.

- This will necessitate significant and immediate adjustments to their existing grant management, reporting, and overall compliance frameworks.

Hidden Expenses: Training, Verification, and System Upgrades

- Implementing new or enhanced eligibility screening processes for immigration status will demand substantial administrative resources from health centers.

- This includes the task of training staff on the new policies, verification procedures, and requisite documentation.

Scrambling for Alternatives: State/Local Funds vs. Federal Limits

- Health Centers often rely on a mix of federal, state, and local funding. The Notice’s immediate effective date requires rapid adjustments to ensure compliance, potentially straining resources for Health Centers already operating on tight budgets. Health Centers may need to identify alternative funding sources (e.g., state or private funds) to serve Non-Qualified Aliens, which could be challenging in areas with limited resources.

- California’s SB 75, SB 104, AB 133, and SB 184 Medi-Cal expansion covers all ages regardless of immigration status, alongside county public hospital and general relief safety-net programs. Health Centers should utilize SB 75, SB 104, AB 133, and SB 184 state funds to preserve access for undocumented patients.

No Time to Adapt: Immediate Enforcement Creates Chaos

- A significant challenge for Health Centers is the immediate effectiveness of the Notice, despite the provision for a 30-day comment period. This means that Health Centers are afforded no grace period to adapt their new systems, conduct staff training, or effectively communicate these changes to their patient populations.

- The lack of prior Notice or preparation time will likely lead to confusion, errors, and significant disruptions in patient flow and service delivery.

V. Compliance Risks and Mitigation Strategies

Health Centers relying on federal funding, such as HRSA’s Section 330 grants, face significant financial, operational, and legal risks if they fail to comply with patient eligibility requirements. These risks include funding clawbacks, where HRSA may recoup misused federal funds if audits reveal services were provided to ineligible patients (e.g., Non-Qualified Aliens) without alternative funding.

For example, if a health center bills a Section 330 grant for a non-exempt primary care visit by an undocumented patient, HHS could demand repayment. Programmatic audits also pose a threat, as HRSA conducts site visits and routine reviews of eligibility documentation. Failure to maintain proper records could result in corrective action plans or grant restrictions.

Legal exposure is another critical concern. Under the False Claims Act (FCA), health centers that knowingly misuse federal funds risk fines of up to three times the misallocated amount, plus penalties per violation. Additionally, Health Centers in sanctuary states (e.g., California, New York) may face conflicting pressures between federal mandates and state/local policies. Beyond financial and legal consequences, reputational harm can occur if patients are wrongly denied care or fear immigration-related repercussions, eroding community trust.

To mitigate these risks, health centers should implement the following strategies:

- Maintain auditable records: Retain copies of immigration status verification (e.g., Permanent Resident Cards, asylum paperwork) for at least five years. Use EHR flags to link patient eligibility to specific funding streams (e.g., “SB 75-funded” vs. “Section 330”).

- Conduct internal audits: Perform quarterly reviews of 10–20 percent of patient files to identify and correct errors before federal audits occur.

- Segregate federal dollars: Use non-federal funds (state/local grants, philanthropy) for Non-Qualified Aliens and clearly document this separation in budgets.

- Enforce strict billing protocols: Never bill Section 330 grants for ineligible services, and train billing staff to flag restricted claims.

- Adopt “safe harbor” policies: Follow HRSA’s forthcoming guidance (if issued) on eligibility verification standards to demonstrate good-faith compliance.

- Train staff on ambiguous cases: Ensure frontline workers know how to handle situations where patients lack documentation but require emergency or exempt care.

- Implement whistleblower protections: Encourage staff to report compliance concerns internally without fear of retaliation.

By proactively addressing these risks through rigorous documentation, internal controls, and staff training, health centers can safeguard federal funding, avoid legal penalties, and maintain trust with their patient populations.

VI. Actionable Steps for Compliance and Adaptation

Immediate Compliance Measures: Screening, Training, and IT Updates

Given the immediate effectiveness of this reinterpretation, Health Centers must undertake swift operational adjustments to ensure compliance and minimize disruption to patient care.

Immediate Legal and Compliance Review of Service Offerings

- Health Centers should immediately conduct a thorough audit of all services funded by federal grants, particularly Section 330 funds, to identify which services are subject to PRWORA restrictions and recommend immediate adjustments to intake processes.

Standardized Verification: Documents and Exemptions

- It is imperative to establish standardized procedures for immigration status verification for all patients seeking federally funded services.

- These protocols must adhere to the statutory exemptions for immunizations and communicable disease treatment, ensuring these public health services remain accessible.

Staff Preparedness: Sensitive Communication and Policy Knowledge

- Provide staff with clear communication tools to address patient concerns and avoid improper denials of care while you await further instruction. Urgent and comprehensive training programs are essential for all relevant personnel, including front desk staff, clinical providers, billing specialists, and administrative teams.

- This training should cover the nuances of the new interpretation, detailed eligibility verification procedures, and sensitive communication strategies for discussing eligibility status with patients.

EHR Modifications: Tagging Funding Sources and Eligibility

- Revise patient intake forms and EHR systems to collect immigration documents.

- EHRs and billing systems must be promptly modified to accurately capture and track patient immigration status, service eligibility, and corresponding funding sources.

Monitor Federal Guidance

- Watch for updates on verification requirements and further HHS or HRSA direction on enforcement, carve-outs, or exemptions.

Financial Survival Tactics: Alternative Funding and Advocacy

To safeguard their financial viability and continue serving their communities amidst these changes, Health Centers should actively pursue strategies to mitigate negative impacts.

Beyond Federal Grants: State, Local, and Philanthropic Options

- Health Centers should proactively identify and pursue non-federal funding sources, including state and local government programs, private philanthropy, and community grants.

- These alternative funds can help support services for Non-Qualified Aliens, thereby reducing the impact of federal restrictions on their ability to access essential care. Explore the use of state/local grants, foundation funding, or sliding fee scale revenue to preserve care access for those affected.

Model Financial Impacts

- Health Centers should model financial impacts under various enforcement scenarios. Forecast changes in Medicaid and sliding fee revenues.

Strength in Numbers: Partnering with Associations and Governmental Entities

- Engaging actively with city councils, county boards of supervisors, the California state legislature, professional associations (such as NACHC or the California Primary Care Association), and patient advocacy groups is crucial.

- This collective advocacy can highlight the profound operational, financial, and public health impacts of the reinterpretation and push for supportive policies or additional funding at the state and local levels to offset federal limitations.

Strategic Service Prioritization

- Health center leadership must carefully evaluate the feasibility of continuing to provide certain services to Non-Qualified Aliens as uncompensated care.

- This requires a delicate balance between upholding their mission of universal access and ensuring the long-term financial sustainability of the organization.

30-Day Window: How to Influence Future Policy

Despite the immediate effectiveness of the Notice, the provision for a 30-day comment period offers a critical, albeit narrow, window for stakeholder input.

- Submit Detailed Comments: Health Centers and their representative organizations should collaborate with NACHC, the California Primary Care Association, and legal advisors to submit a comment to HHS by the deadline, documenting anticipated harm and requesting program-specific exemptions or clarifications.

- Assess Legal Exposure and Monitor Future Guidance: Health Centers should assess legal exposure and continuously monitor for any future program-specific guidance from HHS or HRSA that may provide additional clarification on verification requirements or implementation details.

- Prepare for Compliance Audits: Given the contentious nature of this reinterpretation and the HHS’s explicit legal posture, Health Centers should anticipate potential legal challenges and be prepared to respond to inquiries regarding their compliance strategies.

VII. Conclusion

Health Centers must act immediately by taking proactive steps to comply with the HHS reinterpretation while safeguarding patient access and organizational stability. The HHS notice significantly impacts Health Centers by classifying the Health Center Program as a Federal public benefit under PRWORA, restricting Non-Qualified Aliens’ access to non-exempt services.

This change will likely increase administrative burdens, reduce patient volume, and challenge the financial and operational sustainability of these centers. Public health consequences may arise from reduced access to preventive and primary care for Non-Qualified Aliens, potentially increasing reliance on emergency services. Health Centers will need to adapt quickly to comply with verification requirements, seek alternative funding, and maintain community trust while navigating these restrictions. The Notice’s immediate effective date underscores the urgency for these centers to revise their policies and procedures.

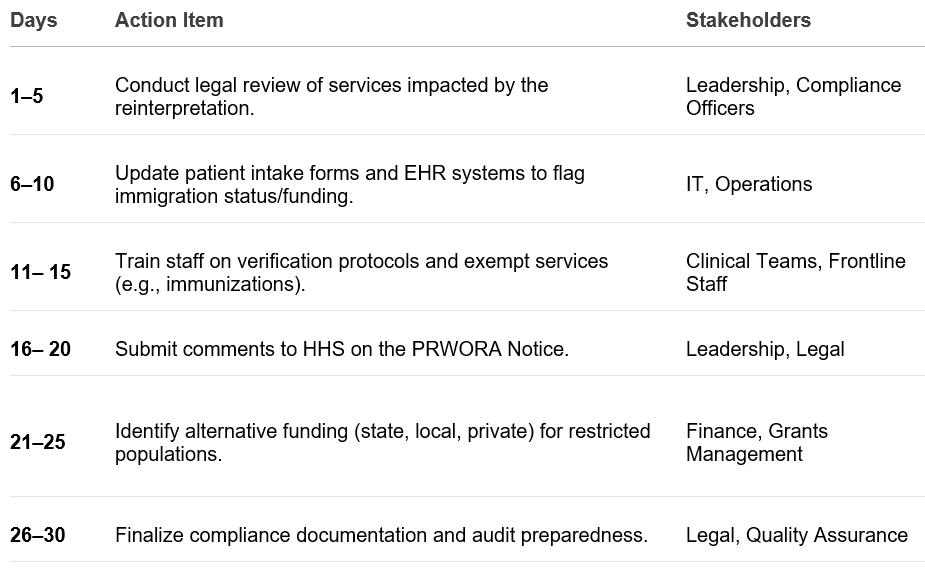

30-Day Compliance Roadmap