One day, in early 1995, Kyle McDonough had a catch-up conversation with an old buddy.

A star center for the University of Vermont hockey team from 1985-89, McDonough was establishing himself as one of the best players in Norway’s top professional league at the time. On the other side of an ocean, the friend was making waves in his own line of work and wanted to share some good news.

“Remember that movie that we talked about?” Adam Sandler asked McDonough. “We’re filming it.”

Set to shoot in Vancouver that summer, the project starred Sandler as a washed-out hockey player who becomes a world-class golfer after learning that his lone on-ice skill — a booming slap shot — translates to the tee box. It wasn’t a huge commercial success upon its February 1996 release, grossing less than $40 million in North American theaters. But “Happy Gilmore” proved pivotal for Sandler on his path to becoming one of the most bankable, beloved presences in comedic history, starring in projects that earned more than $3 billion at worldwide box offices and signing a recent Netflix deal worth $250 million for four films — including the hotly anticipated “Happy Gilmore 2,” which debuted last week.

And it all might have never happened without the elementary school classmate from New Hampshire known to Sandler as simply “McD,” the guy who inspired the original “Happy Gilmore” on a Manchester driving range some five decades ago and remains a close friend.

“You got to talk to Kyle McDonough?” Sandler said at the start of a conversation with The Athletic, a day before the sequel’s release.

“The best. The king.”

McDonough and Sandler first met in the early 1970s, when Sandler’s family moved from New York to Manchester, N.H. Sandler was 5, McDonough was six months older.

They were tight from the jump; McDonough and another friend, Sandler said, walked him to school each day “just so I could feel comfortable.” That scored McDonough major points with Sandler’s mother, Judy.

“(McDonough) was talked about in my house like (he) raised me,” Sandler said.

McDonough came from a family of athletes: Older brother Hubie wound up playing 195 NHL games for the Kings, Islanders and Sharks. Their father, also named Hubie, “was a coach of everything,” Kyle said.

The family, Sandler said, would drive around Manchester in an old Volkswagen bus filled with sports equipment for seemingly every occasion — and it showed.

“Any sport we did, Kyle became better than everybody,” Sandler said. “Best baseball player. Best football player when we were screwing around. Best hockey player by far. Could do the most chin-ups. Could do the most push-ups. Was jacked when he was 8.

“He was just the biggest stud and the nicest, humblest guy in the neighborhood. … My family loved Kyle’s family. The whole family loved him.”

Nobody liked Kyle more than Stan Sandler. When Adam was about 12, a conversation between father and son turned into a discussion about the latter’s future.

“I go, ‘I dunno Dad, I was thinking maybe a pro baseball player,’” Sandler said. “And he goes ‘…Nah. That’s not gonna happen. You’re too slow. It could happen for Kyle McDonough, though.’

“I was like, ‘Yeah, I know (that) could happen. Maybe for the both of us, man.’

“‘Nah. Just Kyle.’”

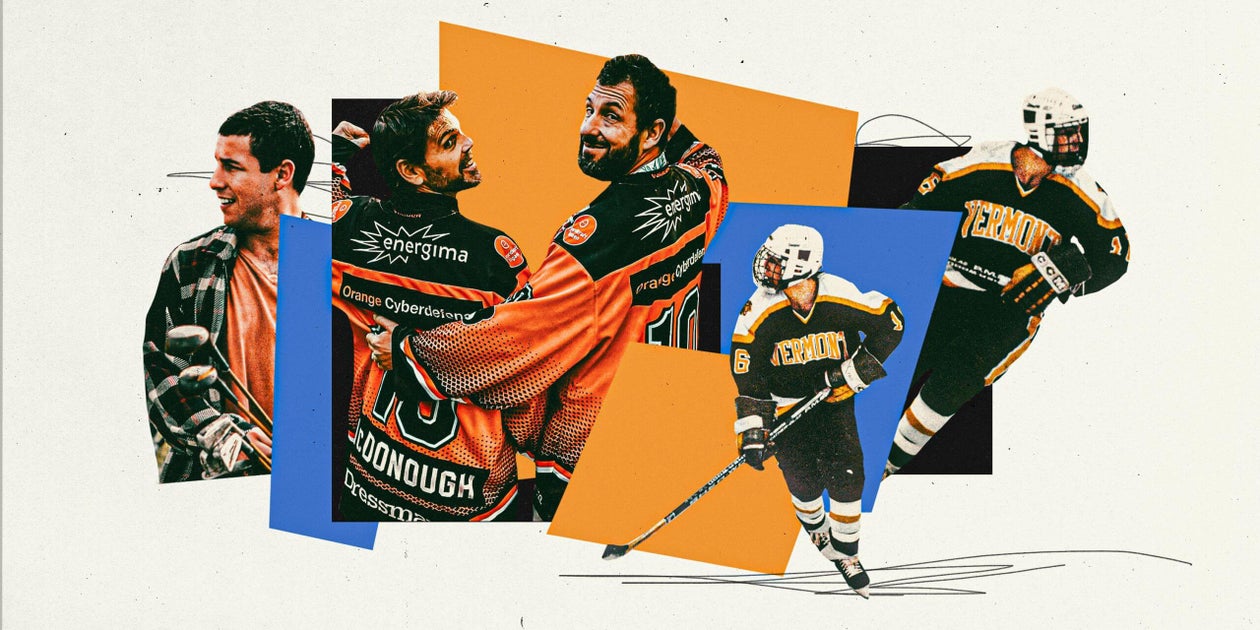

Adam Sandler and Kyle McDonough pose recently in jerseys from Frisk Asker, one of McDonough’s overseas hockey teams. (Courtesy Kyle McDonough)

It made sense, then, that McDonough was invited along for one of the Sandlers’ early trips to the local driving range when Stan was just starting to get into golf. The first time McDonough stepped to the tee, to hear Sandler tell the story, was all it took for the seed of a movie premise to plant itself.

“He was hitting them as a young kid far enough for everybody at the range to turn their heads and go, ‘What’s he doing that I’m not doing?’” Sandler said.

Stan Sandler’s hypothesis, both that day and as the years went on, was that McDonough’s hockey skill and muscles — especially in his wrists — helped him immediately thrive with a club instead of a stick.

McDonough continued golfing with the Sandlers. After losing his own driver, he once even borrowed Stan’s for a long-shot competition … and won. But his legacy in the sport was cemented years later, when Sandler reached into their shared past and began crafting a script about a hockey player with preternatural driving talents.

“It’s a great story,” said Tim Herlihy, Sandler’s longtime writing partner. “It’s great that there’s a real-life Happy Gilmore.”

By 1994, Sandler was acting as a regular cast member on “Saturday Night Live” and already working with Herlihy on a second movie — even before their first, “Billy Madison,” had been released. If Sandler’s pivot from television sketch comedy to feature films was going to happen, it needed to be then.

“They probably wouldn’t have let us make another movie if we waited until ‘Billy’ came out to start ‘Happy,’” Herlihy said.

“We needed to come up with an idea for a movie and we had nothing. So (Sandler) said, ‘I actually went golfing with Kyle McDonough once. And he was whacking it. It was his first time ever playing, and he was hitting it farther than me. What about a hockey player in the golf world?’

“And that was it. It was right there.”

Herlihy, of course, had already heard the lore about the McDonough brothers — he and Sandler roomed together at NYU, an easy drive for some of the latter’s New Hampshire buddies. “They drank the town dry,” Herlihy said. “But they talked about Kyle and Hubie like they were the superstars of Manchester. These guys were just legendary.”

Premiering in summer 1995, “Billy Madison” underwhelmed at the box office and with critics. But “Happy Gilmore” was far enough along for Sandler to break the news to McDonough. The film was shot in British Columbia, and McDonough made the trip. He spent a week watching Sandler on set and crashing with him at his hotel.

“I’m going, ‘I guess this is really happening’,” McDonough said.

The movie went on to significantly out-earn its $12 million budget, guaranteeing Sandler and Herlihy more work. Over time, cable channels and DVD sales have turned “Happy Gilmore” into one of the most beloved comedies of its time — and made the name synonymous with a rage-case, alligator-wrestling golfer who takes a running start on his tee shots and winds up as if preparing to hit a one-timer on the ice.

But the real-life and fictional Happy Gilmores are far from perfect analogues. McDonough’s hockey resume is proof. At Vermont, he led the Catamounts in scoring three out of four seasons; helped the Division 1 program make the NCAA Tournament for the first time; and earned All-American honors as a senior. Only five players in program history have logged more career points, and one is Hockey Hall of Famer Martin St. Louis.

Given McDonough’s temperament – humble and mild-mannered, a coach’s son – some tweaks were necessary for comedy’s sake. Sandler pulled from the other hockey players he grew up with in Manchester.

“They were brawlers and ready to go and could knock back drinks, and I thought it would be funny to see that style of a guy on tour with the other dudes,” Sandler said. “I thought the reason my guy could play was because he bangs them so long that he had an advantage.

“And that was Kyle. His first hit was always 80 yards longer than anyone else.”

The price is wrong: Adam Sandler wears a Bruins jersey as he trades blows with Bob Barker in the original “Happy Gilmore.” (Universal / Getty Images)

They also decided to play up what Herlihy called “the blunt instrument of the temper issue,” which came naturally to Sandler. McDonough, on the other hand, never fought a coach at tryouts: “I got cut (from a team), but not like that,” he said.

Nor did he ever take off his skate and try to stab someone with it. “We have to draw the line somewhere,” he said.

Sandler’s knock-kneed skating on camera was another differentiation point. “God, that was hard to watch,” McDonough said.” I tell everyone, ‘(Sandler) took poetic license with that.’”

Asked to scout himself as a hockey player, McDonough, who was listed at 5-feet-9 in college, showed some of the humility that Sandler mentioned.

“He’s quicker than he is fast. He’ll beat you to that puck right there, but down the ice, it’s not gonna happen. He skates a little funny,” McDonough said.

McDonough wound up playing overseas for 13 years. He piled up points across Europe — Denmark, Scotland, Sweden — but made his biggest mark with Frisk Asker in Norway’s top league, scoring 33 or more goals in three of his six seasons there and leading the franchise to a championship in 2001-02 before retiring.

The closest he came to Gilmore as a hockey player, McDonough said, was during one of those Norway seasons when he led the league in penalties. Naturally, he also won its scoring title.

Every year, his students sniff out the Sandler connection. Typically, it doesn’t happen until after Christmas. Then someone lands on the correct search results, or sifts through the entirety of the DVD special features on YouTube. And the whispers begin.

For his part, McDonough leans in. Now a high school social studies teacher in Manchester, he appreciates the cachet — even if he refuses to directly answer their questions.

“(I) kind of play it off. I’ll deny it,” McDonough said. “They know that (Sandler) came from here, so it’s plausible. All I say is, ‘Someone had to go to first grade with him, right?’”

Nearly 30 years after Happy Gilmore sank a circus shot with a hockey stick putter to win the gold jacket at the Tour Championship in the original movie, the sequel features a stronger hockey presence. Retired NHLers Sean Avery and Chris Chelios play a pair of bodyguards, credited as Henchman No. 1 and Henchman No. 2. Happy has four sons — all hockey players. He golfs in updated Bruins gear on the screen and, in character at last month’s NHL Draft, announced Boston’s first-round pick. That player, James Hagens, later met Sandler at the New York premiere of “Happy Gilmore 2.”

Adam Sandler meets Bruins draft pick James Hagens at the “Happy Gilmore 2” premiere. (Kevin Mazur / Getty Images for Netflix)

The movie also attracted extra attention for its sheer tonnage of celebrity cameos and family-reunion vibes. Bad Bunny is Happy’s caddie! John Daly lives in Happy’s garage! Travis Kelce gets (redacted) by a (redacted)! Sandler’s daughters! Herlihy’s son! All pop up, in some fashion.

So does McDonough, who made the final cut as a caddie for Charles Howell III. He attended the premiere, too, where he was particularly excited to talk to Judy Sandler. Stan Sandler passed away in 2003 at 68, three years after Sandler released a spoken comedy album called “Stan and Judy’s Kid.”

“I hate to say it, it’s so cliché: (Sandler) is one of the guys,” McDonough said. “I’ve never been with him where he said no to a picture. And it’s everywhere. It’s constant. It’s so unbelievable. How he’s stayed like he is, is just baffling. It comes back to Stan and Judy.”

Given the sequel’s summer publicity rounds — Sandler mentioned McDonough’s name on the Kelce brothers’ podcast, for one — the whispers around the real-life Happy Gilmore might start earlier than normal when school begins on Sept. 5.

Another recent development for McDonough: After more than 20 years on the bench, including for his former high school and current employer at Manchester Memorial, he’s done as a hockey coach.

Now, he coaches golf.

(Illustration: Kelsea Petersen / The Athletic; top photos: Getty Archives, UVM Athletics)