By Jaymie Baxley

In the winter of 2021, social workers in rural Wilson County were overwhelmed by a surge in reports of adults with disabilities being abused.

In a typical month, the county’s Department of Social Services receives about 30 such complaints. But that February, the agency fielded 33 reports in just seven days.

When Nichole Atkinson, manager of the department’s Adult and Family Services program, began to investigate, she noticed a common thread: The reports all originated from residences known as Multi-unit Assisted Housing with Services, or MUAHS.

Unlicensed and largely unregulated, the houses occupy a gray area in North Carolina’s long-term care system. They are broadly defined by state law as facilities where patients can choose their own service providers and where personal care is “arranged by housing management.”

That essentially makes them independent living settings — places where residents retain autonomy and are free to come and go, hire their own caregivers and manage their own finances. Yet many of the complaints received by Atkinson’s office described situations in which residents with behavioral health conditions were being denied access to their money, food stamps and medication — basic resources they were supposed to control themselves and have rights to.

After some digging, she learned that several MUAHS houses in Wilson County had been misleadingly advertised to residents’ families and doctors as assisted living communities, which in the public imagination can conjure up visions of dining rooms and plentiful recreation, along with assistance with health needs.

These facilities were anything but. Atkinson said MUAHS operators are only legally required to provide residents with a daily meal. In some houses, simple furnishings like bed frames are considered amenities.

But the deceptive advertising, she said, is technically allowed under state law, which confusingly classifies the houses as one of three types of “assisted living residence[es]” recognized in North Carolina.

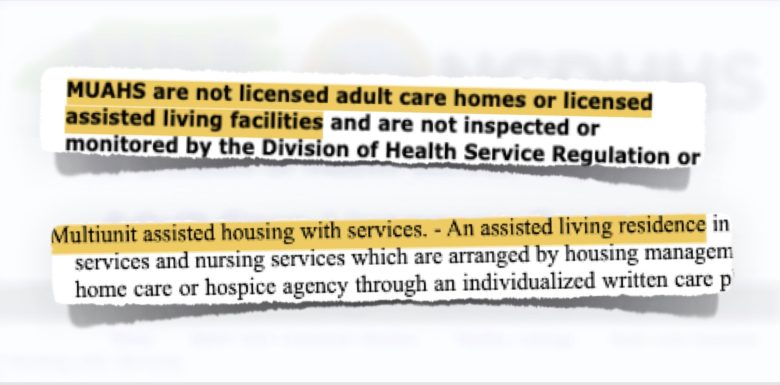

Text on the N.C. Division of Health Service Regulation’s website, top, notes that MUAHS houses are not licensed assisted living facilities, but state law defines them as assisted living. Credit: Jaymie Baxley/NC Health News

Text on the N.C. Division of Health Service Regulation’s website, top, notes that MUAHS houses are not licensed assisted living facilities, but state law defines them as assisted living. Credit: Jaymie Baxley/NC Health News

The houses are not subject to routine inspections and monitoring like assisted living facilities, nor are their residents protected by the state’s Care Home Bill of Rights.

“These homes have no oversight,” Atkinson said. “No one is required to go in to make sure that they have proper zoning and proper construction, or that proper rules are in place. There’s no vetting of who owns or operates them.”

The hospital incident

In the years since that rash of reports, the houses have been a persistent problem in Wilson County.

Then came the hospital incident.

On the weekend of Aug. 12, 2023, a local MUAHS operator brought all 34 of his residents to the 20-bed emergency department of Wilson Medical Center. All of them had behavioral health issues.

Chris Munton, then CEO of the hospital, said the department’s emergency staff typically treat three to four behavioral health patients a day. It usually takes six more days, he said, to find a place that can provide those patients with an “appropriate level of care” after they’ve been discharged.

Hospital staff and administration scrambled to meet the needs of a large group of people with lots of needs. The influx of patients forced Wilson Medical Center to activate a special command center typically used during hurricanes and other natural disasters.

“It was discovered that an owner of multiple MUAHS in the area had gone out of town and did not have anyone to provide the required one meal a day for their residents,” Munton told the city council in Wilson, the county seat, during a June 2024 meeting. “To solve this dilemma, the owner brought all their residents to the ED.”

Chris Munton, former CEO of Wilson Medical Center, describes an incident involving a local MUAHS operator who dropped off 34 of his residents at the center’s emergency department.

The incident led to an audit that revealed more than 60 percent of all behavioral health patients seen at Wilson Medical Center from 2021 to 2023 had been residents of MUAHS houses. An “alarming” number of those patients had traveled from other states to live at the facilities, according to Munton.

Some MUAHS operators, he added, appeared to be using the hospital as a “holding station” for residents who “become too aggressive or unstable.”

“These patients often do not require immediate health care assistance but are left at our facility to alleviate unwanted disruption within the MUAHS house,” he said. “Without any accountability or guardrails to how these MUAHS operate, Wilson Medical Center is left to care for and find placement for these patients, even if they do not require emergency care.”

Munton left Wilson Medical Center less than two months after his remarks to the council. The hospital did not respond to written questions from NC Health News.

Unwitting epicenter

MUAHS houses have existed in the state since 2001, when the N.C. General Assembly passed legislation recognizing them as part of a broader effort to expand residential options for older adults and people with disabilities.

The goal was to provide a flexible model of care that would allow residents to live more independently than in traditional adult care homes or nursing facilities, while still having access to support services. These settings were intended for individuals capable of directing their own care, and the state placed fewer regulatory requirements on them than on licensed facilities.

Over time, however, the lack of oversight has made the houses a “regulatory black hole,” said Corye Dunn, head of public policy for Disability Rights North Carolina.

Unlike adult care homes, which must meet staffing and quality standards, MUAHS facilities operate with minimal state involvement.

Kimberly Irvine, director of Wilson County DSS, said this regulatory gap, combined with growing demand for affordable housing and supportive care, has created a system ripe for abuse.

“This program was developed to be an alternative to more expensive, restrictive nursing home care,” she said. “But with the lack of regulations and [no] licensing requirement, that has kind of opened the door for people that want to exploit our disabled and elderly.”

“The state has very little power, but very vulnerable people are often housed there,” said Dunn, whose organization also has access to the facilities.

The number of MUAHS houses in North Carolina grew significantly in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, which exacerbated the nation’s ongoing mental health crisis and intensified demand for community-based housing for people with disabilities. An NC Health News analysis found that just 87 of the state’s 141 registered houses were in business before 2020.

Wilson County, which had no MUAHS houses before the pandemic, has become the unwitting epicenter of that growth. Fourteen facilities have set up shop there over the past five years, more than any other county in the state over the same period.

And that’s just counting the ones that are registered. Irvine said several houses in the county — ranked as the state’s 25th most populous by the U.S. Census Bureau — are being run off the books with near impunity.

“Operating one of these facilities without being registered is the lowest misdemeanor with the lowest fine,” she said. “They’re going to pay the fine and continue to operate, so there really is no penalty.”

Atkinson, the DSS program manager, noted that some houses in Wilson County are “actually run properly.” But for reasons she and others don’t fully understand, the community has become a hot spot for unscrupulous operators.

Behind closed doors

Many of the so-called facilities in Wilson County are little more than aging single-family dwellings scattered across residential neighborhoods — indistinguishable from the homes around them.

The operators make their money, she said, by withholding residents’ Social Security benefits. They also claim any payments made to residents through the state’s Special Assistance In-Home program.

“The individuals are really not seeing any benefit from their Social Security check, in addition to their Special Assistance In-Home payment,” Atkinson said, adding that some operators collect as much as $1,900 a month per resident.

Dunn said she has seen operators charge “surprisingly high rental rates for surprisingly poor conditions with poor access to food and services.”

There have also been cases, she said, in which the owners of licensed facilities with more oversight, such as family care or adult care homes, have opened MUAHS houses.

“They recruit someone to the licensed facility and then after a while, if they’re the right profile, they let the person know, ‘Hey, there’s another opportunity and do you want to move in?’” Dunn said.

“These are options that are designed to extract as much money as possible from people with disabilities,” she added. “Once that bed opens up in that licensed facility, they have a pipeline of people to come in to the more profitable MUAHS.”

County social workers have documented troubling conditions inside the homes.

In several cases, Atkinson said, residents were found sleeping on bare mattresses placed directly on the floor. Others were living four or more to a room, crammed into tight quarters with no privacy.

An NC Health News review of incorporation filings and local tax records found that several houses in Wilson County are not even owned by the entities that operate them.

“We’ve had some encounters where we found out operators were renting from rental properties,” Atkinson confirmed. “During our evaluations, we learned that some of the landlords did not know that the properties were being used as businesses. They thought they were renting to one person.”

Wilson Mayor Carlton Stevens did not respond to messages seeking comment from NC Health News, but local elected officials have indicated they’re aware of the issue.

During the June 2024 board meeting, Councilman Donald Evans acknowledged that Wilson had been experiencing “problems with these facilities for quite some while.”

“They can move into any neighborhood, set up homes anywhere they want to without notifying anybody, and that’s a real problem that I have,” he said of the houses’ operators. “They should not be allowed to move anywhere they want to within our city without us having any control over it.

But the city’s hands were tied, Evans said, because the houses are authorized by the state.

‘Basic human standard’

As chairman of the board that oversees Wilson County Department of Social Services, Dante Pittman is well acquainted with the community’s MUAHS predicament.

Last November, the 29-year-old Democrat was elected to represent the district that covers Wilson County in the N.C. House of Representatives, giving him a legislative platform to tackle the issue.

“I told our board that I’m tired of just talking about it,” he said in an interview with NC Health News. “It’s time that we at least introduce some legislation and work with our partners at the state level.”

In April, Pittman filed a bill that seeks to enhance regulation of MUAHS houses. Among other things, it would prohibit the houses from being advertised as assisted living facilities and would ban operators from accepting residents with significant cognitive or functional impairments.

When discussing the proposed legislation with his fellow lawmakers, Pittman is quick to point out that he doesn’t want to eliminate the houses. His goal, he said, is simply to ensure they’re subject to some level of oversight.

“I’m careful when I speak with folks because I don’t want them to think that I don’t see housing, or the lack thereof, as a tremendous problem,” Pittman said. “I understand that, and I’m working with others to try to address it, but there’s got to be a basic human standard that’s a part of this solution.”

State Rep. Sarah Crawford (D-Raleigh) is co-sponsoring the bill. Outside of politics, she serves as CEO of TLC, a Wake County nonprofit, formerly known as the Tammy Lynn Center, that provides residential services to adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

“We’re regulated by everybody and their brother, sister and second cousin,” she said of her organization. “We have many, many eyes on us, and we have to make sure that we’re following all the rules because every individual deserves the right to live in a safe environment.”

State Reps. Dante Pittman, left, and Sarah Crawford have sponsored legislation that would enhance regulation of MUAHS facilities. Credit: NC General Assembly

State Reps. Dante Pittman, left, and Sarah Crawford have sponsored legislation that would enhance regulation of MUAHS facilities. Credit: NC General Assembly

Crawford doesn’t think the changes proposed in Pittman’s bill would harm MUAHS facilities that are being run the way they were originally intended to be. She said it might, at worst, create “some additional paperwork” for operators, but the burden “should be very minimal.”

“If they’re doing the right thing, they shouldn’t have any fear,” she said. “But we need to have a process for getting bad actors either out of the business or helping them make reformation so that they can provide better care.”

Once filed, though, the bill has not progressed at the legislature.

Stopping a spread

Most of the state’s MUAHS facilities are not run like the ones in Wilson County. In fact, they stand in stark contrast.

Cambridge Village Optimal Living has 422 units across three campuses in Wake and New Hanover counties, making it by far the largest MUAHS operator in North Carolina. The company’s newest site, The Cambridge at Brier Creek in Raleigh, boasts 132 one-bedroom and 63 two-bedroom units — the most of any facility registered with the state.

Its other facility in Wake County, Cambridge Village of Apex, is a 121-unit campus that has been registered since 2011. Cambridge Village of Wilmington, the site in New Hanover County, launched in 2017 with 106 units.

At each facility, residents have access to a wide range of amenities and on-site health care services from licensed providers.

But Cambridge, which did not respond to a request for comment from NC Health News, advertises the campuses as independent living communities, not assisted living settings. Their website boasts of chef-driven restaurants, salons and heated swimming pools — a far cry from the houses in Wilson County, which don’t even have websites.

Nash County, which neighbors Wilson and is also represented by Pittman in the General Assembly, is home to 16 MUAHS facilities — the most of any county in the state. In an email to NC Health News, Denita DeVega, director of the Nash County Department of Social Services, said her office hasn’t “encountered any significant problems” with the houses there.

But Pittman believes it’s only a matter of time before the issues reported in Wilson County begin occurring in other communities.

“If we don’t take care of this now, I’m afraid we will see it replicated all across our state,” he said.

This article has been updated to clarify that Disability Rights North Carolina has access to MUAHS facilities.

Republish This Story

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under a Creative Commons license.