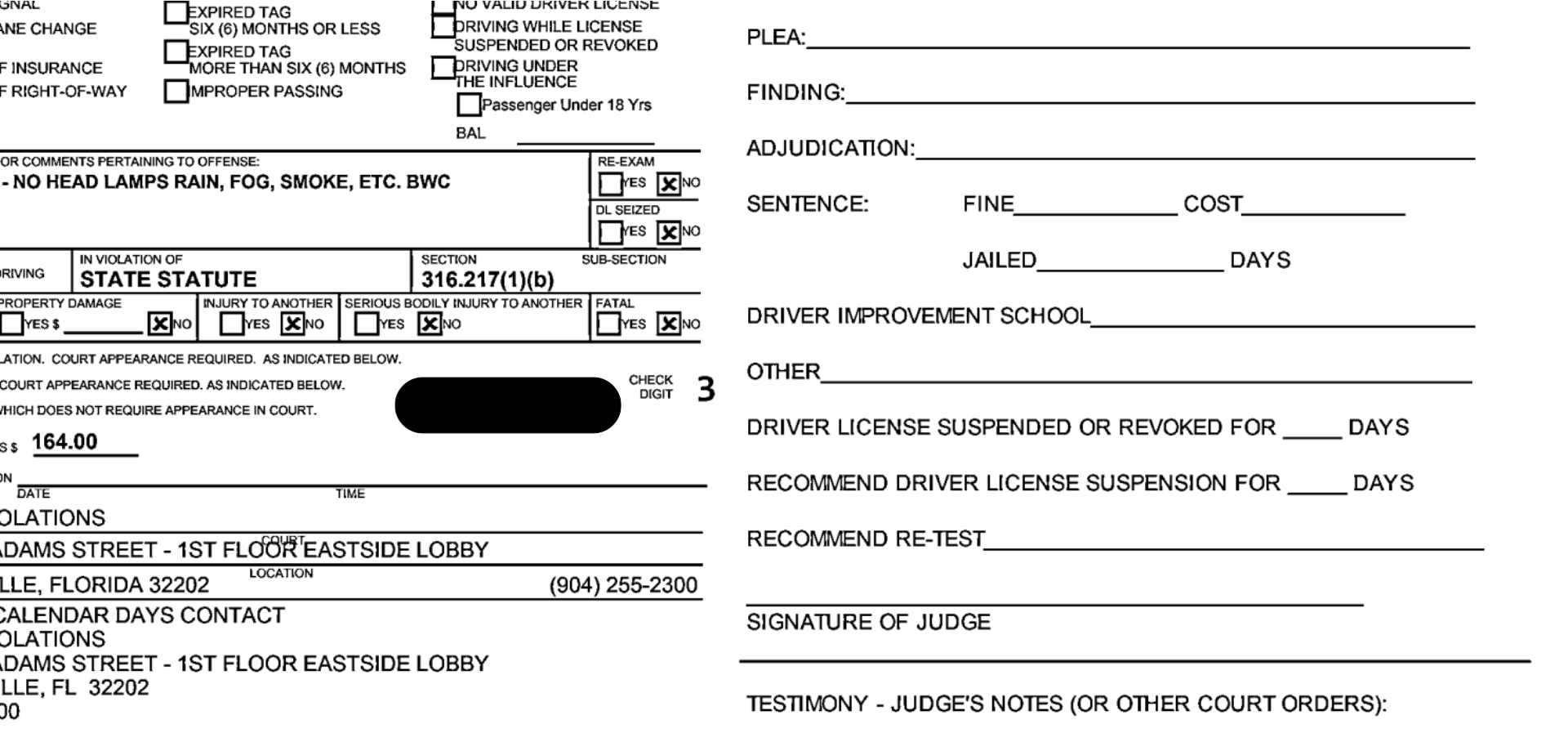

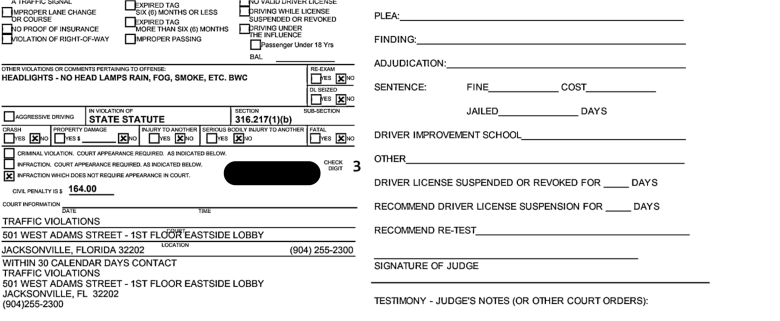

An example of the citations given to drivers who are stopped for driving without their headlights on during inclement weather in Duval County. [Courtesy of Duval County Clerk of Court’s]

An example of the citations given to drivers who are stopped for driving without their headlights on during inclement weather in Duval County. [Courtesy of Duval County Clerk of Court’s]

Driving in the rain without headlights, the reason William McNeil Jr. was pulled over before he was hit and then dragged from his car by Jacksonville sheriff’s deputies, is an exceedingly rare infraction in Duval County. But it is less rare if you are Black like McNeil, according to more than three years of traffic-stop data obtained by The Tributary.

Video of the February stop, filmed from McNeil’s cellphone, went viral last week and prompted a PR blitz by Jacksonville Sheriff T.K. Waters to defend his agency’s handling of the arrest, which he said remains under an administrative review. The State Attorney’s Office cleared the traffic stop of any criminal charges on the part of the police, authorities have said.

The traffic stop has nonetheless reopened long-simmering questions about how JSO treats Black residents, and the wisdom of what are known as pretextual traffic stops – a tactic in which police stop drivers for minor traffic infractions with the underlying goal of searching the car. Critics of such stops have said they disproportionately affect Black drivers and erode community trust.

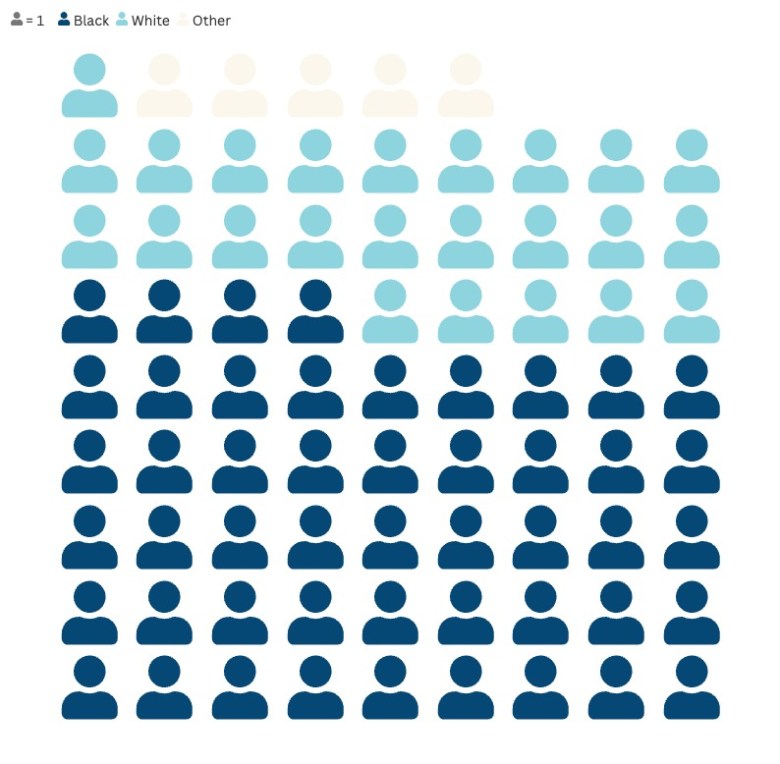

The citation figures obtained by The Tributary suggest that Black drivers are scrutinized far more closely than white motorists.

From 2021 through July of this year, Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office deputies wrote tickets for “no headlamps” in rain, fog or smoke at least 78 times, according to records from the Duval Clerk of Courts, with the vast majority – about 63 percent – going to Black drivers.

Regina Wright, a local defense attorney, was not surprised by the disproportionate number of Black drivers stopped.

“That’s how they police mostly Black neighborhoods,” she told The Tributary. “They look for minor traffic offenses so they could stop the car, possibly smell marijuana and search the car.”

For an agency that conducts tens of thousands of traffic stops each year, the headlight violation is an obscure citation. By contrast, a similar request for data about seatbelt violations over the same time span generated more than 20,000 citations.

That data is based on citations recorded by the clerk’s office, and provided to The Tributary, for every citation given to drivers under the same state statute McNeil was ticketed for.

Of the total number of tickets analyzed by The Tributary, eight included citations given by other Duval County police departments or the Florida Highway Patrol. Just three of those tickets – or 37.5% – were given to Black drivers.

Though the violation is only cited on average twice a month in Duval County, the The Tributary found that one patrol officer is responsible for more than a quarter of all tickets and that on one day in August last year, he cited 17 people within three and a half hours, with most of those tickets being written just five to 10 minutes apart.

McNeil, alongside his attorney, national civil rights lawyer Ben Crump, said last week he plans to sue JSO, the officer who punched and dragged him out of his car and the other officers who were involved in his stop.

McNeil’s stop

When Officer Donald Bowers pulled McNeil over in a neighborhood near the intersection of Edgewood Ave. North and Commonwealth Ave. on the Westside, McNeil immediately opened his driver’s side door to ask why he was stopped. He explained to Bowers that his window didn’t work.

Bowers said he was pulling him over for not having his lights on, and for not wearing a seatbelt. McNeil said it wasn’t raining and Bowers responded that he wasn’t going to argue with him.

There were raindrops on McNeil’s car, but it was not raining in any of the body camera videos released by JSO.

McNeil shut the door and started to record from inside his car. Bowers told McNeil multiple times to exit the car and told him he was under arrest for resisting without violence, then he called backup. Eventually, at least three other officers showed up to the stop.

McNeil asked the officer to call his supervisor multiple times. He later said at a press conference that he didn’t exit the car because he was scared.

About three minutes into the stop, a second officer pulled up and started to talk with McNeil from the passenger side window. Just 57 seconds into their conversation, Bowers said he was going to break the window and did.

McNeil’s video shows that Bowers hit an unmoving McNeil in the face before unlocking the door and dragging him out of the car. McNeil raised his hands when told to and did not resist being cuffed. A police report says that he punched McNeil an additional six times in his right thigh.

The hit to McNeil’s face can’t be seen from the body camera footage, which was positioned at a different angle than McNeil’s in-car cellphone, and the strike was not mentioned in the arrest report.

Officers also wrote in a response-to-resistence form that McNeil reached for a knife that was on his floorboard, which was discovered after he was cuffed.

None of the videos back up that claim.

JSO’s response

McNeil’s own video, which he posted to social media on July 20, sparked nationwide outrage and drove Waters to hold a press conference and release body camera footage the next day.

McNeil asked for him to pull the law up, and Miller refused until he exited the vehicle. Soon after that is when Bowers broke the window.

Waters said the State Attorney’s Office had already cleared the officers of any criminal charges and that his office was still investigating the stop internally for any potential violations of JSO rules.

Although Waters said he was reserving judgment about the stop, he nonetheless was defensive about Bowers’ conduct and implied that McNeil’s video was misleading the public.

When a reporter asked why Waters thought it was appropriate that Bowers landed a “sucker punch” on McNeil, for example, Waters disputed that characterization.

“First of all let me stop you, not a sucker punch,” Waters said, interrupting the reporter. “I’m not excusing that administratively … there are things that we definitely need to look at, but the context of this video should tell you everything you need to know.”

Asked again about the sucker punch, Waters said “it is what it is,” saying that body camera videos add additional context to what McNeil released himself.

Waters has not acknowledged that the stop was pretextual, though in an interview on First Coast Connect last week he noted that such stops are legal. “Driving is not your right,” Waters said. “Driving is a privilege that’s afforded to you by the state of Florida. If you get stopped for a lawful reason, you have to you you you have to comply.”

Wright, the defense attorney, said the hit reflects what JSO officers are trained to do.

“The punch was outrageous but it’s in JSO’s policy, it’s how they’re trained,” she said. “I’ve heard time and time again in depositions where officers were not afraid to say that they call them compliance strikes … this force is not unusual.”

During the conference, Waters also admonished McNeil for releasing the video without making a formal complaint to JSO first, calling it part of an anti-police agenda.

Two years earlier, Waters held a press conference in which he announced arresting a man who he said filed an administrative complaint against a different officer. The complaint alleged an officer used excessive force and illegally searched him during a traffic stop. Body camera footage from that arrest did not match with the story the man reported to police and he was arrested for filing a false report.

“By taking decisive action in this case, we are sending a clear message that victimizing our officers in order to push an agenda will not be tolerated,” he told reporters.

What the data shows

McNeil is one of 78 drivers who have been stopped by JSO for driving without their headlights out during inclement weather since January 2021.

During his stop, McNeil told the officers that it wasn’t raining, to which Officer Miller responded, “it doesn’t matter you’re still required to have lights on.”

State statute says that drivers must have their lights on “during any rain, smoke, or fog.”

Of the 77 other tickets, one officer – B. Reinert – is responsible for at least 28 of them, 19 more than the next highest officer. And of those, 17 occurred on the morning of Aug. 6, 2024, a day where weather reports say it was misting in Jacksonville.

Drivers were stopped on Highway 115, with the majority of them at the east J. Turner Butler Blvd East on ramp, near the St. Johns Town Center.

In seven of those cases, Reinert wrote a citation within 5 to 7 minutes of each other.

JSO did not answer questions about Reinert’s enthusiasm for the citation, including if officers are assigned to dole out those specific tickets, how it’s possible that Reinert wrote so many within such a short period of time and what the time on citations should indicate: is that when the ticket is actually written or when the car is first stopped?

Wright said driving with headlights off when it’s raining is a legitimate reason to pull someone over, but agreed the video doesn’t show rain falling during the stop.

She also said that during a lawful stop, drivers have to comply and exit their vehicle if asked and they must give officers identification.

Nichole Manna is The Tributary’s senior investigative reporter. You can reach her at nichole.manna@jaxtrib.org.

Related