Willa Robinson has loved to read since she was a child. It’s a passion passed down from her father, who “read everything” and tended to fall asleep on Sunday afternoons with the newspaper over his face, she told me.

The 84-year-old Robinson first began collecting books in the late 1970s, when she would spend her lunch hour in the bookstore up the street from the Kansas City Post Office where she worked. After she transferred to a downtown branch a decade later, she found books at a nearby Salvation Army. She sought out books on the Holy Spirit, but “every time I would go looking for a book on the Holy Spirit, there would be books about Black history,” she recalled. This is when “the fever, the passion for Black books” entered her life. “The spirit of God placed this hunger in my heart for Black history.”

Collecting books by Black authors took on a greater importance in her life after the loss of her daughter and granddaughter.

“I know why people hoard,” she said. “It’s because they’re trying to fill an empty spot. And the empty spot that I was trying to fill was my daughter and my granddaughter that were gone.”

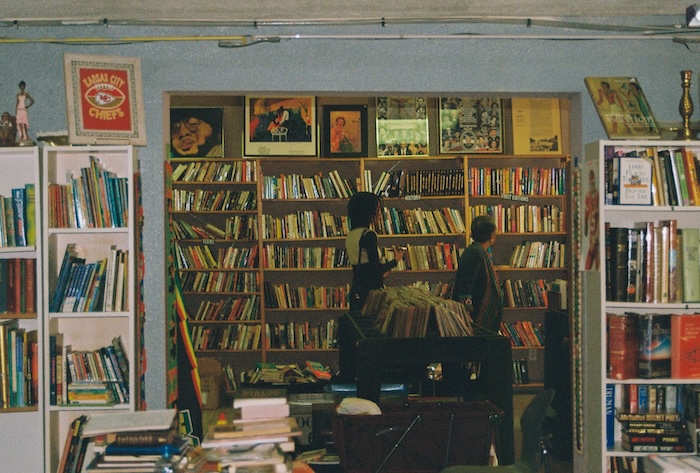

Robinson in Willa’s Books and Vinyl. Jade Williams with The Kansas City Defender.

At first, collecting books was a personal pursuit. But as her collection took up more and more space at home, Robinson began selling books — first out of an empty room in a Kansas City federal building; then as a street vendor in the mid-90s; then out of her first store in 2007. Willa’s Books and Vinyl reopened at its current location in 2021. The business, in its various iterations, is the oldest Black-owned bookstore in Missouri and the collection now exceeds 20,000 books. Some date back to the 19th century — the collection includes first editions by Frederick Douglass, Zora Neale Hurston, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Booker T. Washington, W.E.B De Bois, and Langston Hughes.

Robinson told me she never saw Black people — and Black children — in books growing up. “One of the reasons that I got into books was that I thought Black children need to see themselves in books,” she said. (When a Black child came into her store, she’d sometimes give books away to them for free.)

This month, Robinson retired, and Willa’s Books and Vinyl closed its doors. But thanks to The Kansas City Defender, a local news nonprofit, the collection isn’t going anywhere. Instead, the Defender is fundraising to purchase the collection and turn it into a public archive, making “Miss Willa’s” bookstore space into its first-ever public headquarters.

For the Defender, taking over this space and purchasing the archive are examples of what it means to go beyond news coverage to serve its community.

Nina Kerrs first walked into Robinson’s store in the winter of 2023. At the time, Kerrs was volunteering for the Defender, which she loved, but was unhappy in her day job, and “looking for something that I could do with my time that felt fulfilling and purposeful to me,” she said.

Kerrs, who’s 22, “totally fell in love with [Robinson] and her store and the atmosphere,” she said. The store was homey, full of books stacked up to the ceiling, with vinyl records playing in the background. (The first book Kerrs bought there, she said, was Black Nationalism and the Revolution in Music, by Frank Kofsky.) Kerrs began spending time with Robinson, helping her around the store. She described Robinson as one of her best friends and “a legendary person to me.”

For Robinson, the upkeep of the store was becoming a physical and financial burden, and family members were encouraging her to retire. Last summer, after speaking with an out-of-state antique dealer interested in auctioning off her books, Robinson told Kerrs she had decided to shutter the store and sell her collection.

“I was really taken aback,” Kerrs told me. The store was a place she felt safe, and had become a sort of second home. “I immediately came to the Defender about it…I was just like, guys, I’m really worried we are about to lose our longest-standing Black bookstore, and we are going to lose a huge staple for Black culture in our city. And this is terrifying. What can we do?”

Robinson and Kerrs in the bookstore.

The team, Kerrs said, was responsive to her distress. Within a day, about five volunteers from The Defender met with Robinson. They told her how much her store, and collection, meant to the community.

“We didn’t know how any of this would work, but we were just like, give us a month to try to come up with a plan,” Defender founder and executive editor Ryan Sorrell told me. (Sorrell added that he’s purchased a Richard Wright autobiography, a James Baldwin book, and the autobiography of Ida B. Wells from Robinson’s store.)

This was Robinson’s first introduction to the Defender. “It’s this wonderful group of young people,” she said. “They came in, and were very kind, very supportive of me and the books.” She agreed to give them that time.

“We see very broad attacks on Black education, Black literacy, Black information in Missouri,” Sorrell said. “With the rise and proliferation of disinformation and the erasure of Black histories, the thought of her having to sell this bookstore that literally houses first-edition Frederick Douglass books, that houses books dating back to 1863 — the thought of losing that history, particularly in this political moment, was devastating.”

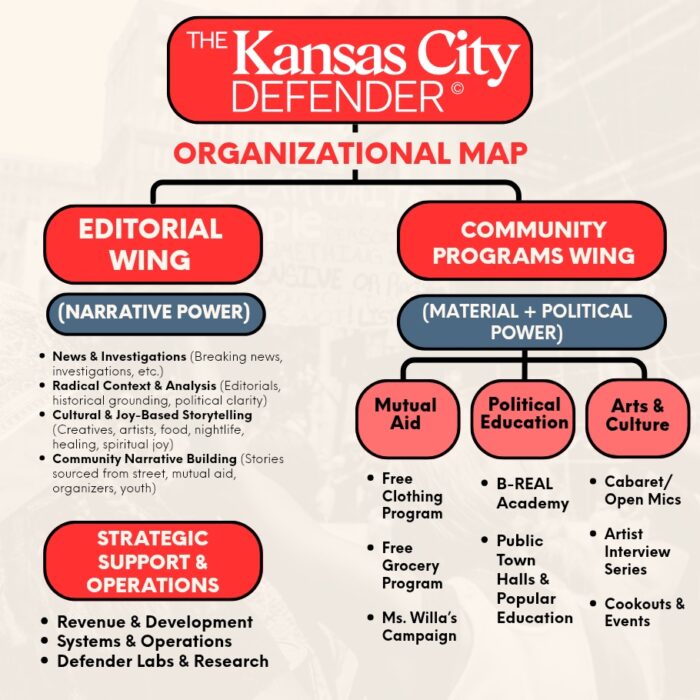

While the Defender is a news organization, it has long seen its mission as broader and deeper than reporting alone. On top of its editorial operations, the Defender runs a community programs wing, which provides mutual aid such as free grocery and clothing programs. Sorrell described this work as a “very organic evolution” from the Defender’s purely editorial roots. When the Defender broke the story about a serial killer targeting Black women in Kansas City in 2022, many readers reached out wanting to volunteer or take some kind of action; the Defender ultimately organized a vigil for the women killed. “That was a moment of realization, for me, that we did need this entire second wing of the organization,” Sorrell said. One local who got involved with the Defender’s community programs after that vigil: Kerrs.

While the Defender is a news organization, it has long seen its mission as broader and deeper than reporting alone. On top of its editorial operations, the Defender runs a community programs wing, which provides mutual aid such as free grocery and clothing programs. Sorrell described this work as a “very organic evolution” from the Defender’s purely editorial roots. When the Defender broke the story about a serial killer targeting Black women in Kansas City in 2022, many readers reached out wanting to volunteer or take some kind of action; the Defender ultimately organized a vigil for the women killed. “That was a moment of realization, for me, that we did need this entire second wing of the organization,” Sorrell said. One local who got involved with the Defender’s community programs after that vigil: Kerrs.

That structure offered a foundation for the Defender to step up for Robinson in some ways that might seem unusual for a news organization.

In August 2024, the Defender began paying the store’s rent for Robinson. On the editorial side, the Defender put together a story spotlighting her need for support that it co-published with the Kansas City Call, the city’s historic Black newspaper, resulting in about 80 people reaching out to volunteer. Next, Kerrs and campaign co-director Lauren Winston organized a team of 40 volunteers, who spent six to eight months cataloguing Robinson’s collection of 20,000+ books. (Kerrs is now on staff, but everyone else was a volunteer, Sorrell said. Some volunteers had library and archival backgrounds.)

After consulting with a local coaching hub for Black entrepreneurs, the Defender formalized its plan. Next month, one year since it began covering Robinson’s rent, the Defender will launch a capital campaign to raise $500,000. Two-thirds of that will go toward purchasing Robinson’s collection. The rest goes toward renovations, rent, and hiring a staffer (or increasing a staffer’s hours). The Defender already has a verbal agreement with the landlord for a two-year lease, and plans to reopen between December and early 2026.

Aside from hosting the public archive and serving as an operational HQ, the Defender plans to move its storage of free clothing to the space, and will host its Abolitionist Freedom School (a 14-week program for a cohort of 20 students, from teens to retirees) there. Its backroom will serve as a video production “creator” space.

It’s especially good timing for the Defender to create a physical HQ, Sorrell said, because of how much the organization has expanded. It now has four full-time staffers, seven part-time employees, and 15 volunteer leaders.

Robinson, for her part, was skeptical at first about the idea of creating a public archive, she told me. She’d hoped the space would remain a store. “But once they explained to me what they were going to do, I agreed to it,” she said. “The young people are the ones [with] ideas, they got the energy to carry it out…I think the young people can do it better than I can do it now.”

Before starting the Defender, Sorrell researched the history of the Black press. He found “historically, the Black press was the second most influential institution in Black communities outside the Black church, and that was because of the actual physical spaces,” he said. “They served as community centers in the Black community.”

This move, he said, enables the Defender to “directly follow in that legacy of the Black press serving as more than just a disconnected news outlet, and actually being a hub in the community, and a place that people feel safe to go to.”

Photo inside Willa’s Books and Vinyl by Jade Williams with The Kansas City Defender.