Gordon Parks, “Worker from Portland Bulk Plant opens a control valve,” 1944.Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks, “Worker from Portland Bulk Plant opens a control valve,” 1944.Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

That’s where Herklas Brown came in. Brown was the proprietor of that establishment. It was in Somerville. Somerville had fewer than 300 residents, and the store was its only business. Brown was also postmaster and, with his brother, drove the local snowplow. He and Somerville could have stepped out of a Norman Rockwell illustration. It was just the sort of wholesome association Esso prized.

Gordon Parks, “Herklas Brown, Somerville, Maine,” 1944.Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks, “Herklas Brown, Somerville, Maine,” 1944.Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

Parks struck an expert balance between evoking American timelessness and honoring the camera’s realist precision. Epitomizing that balance is a photograph of a hay wagon being drawn by two oxen outside of Brown’s store — with an Esso gas pump prominent in the foreground (so’s a Coca-Cola sign). A more subtle nod to tradition is a photograph of Mrs. Brown filling a lamp with kerosene (another petroleum product). There was nothing quaint or antiquarian about her doing so. Somerville, though just 15 miles from Augusta, the state capital, lacked electricity.

Augusta was another of the places Parks photographed in Maine, along with Portland (the harbor), Pittsfield (a training facility for Navy aviators), Windsor (a county fair), Skowhegan (farmers). By Maine standards, he didn’t rack up the mileage, but he managed to cover an awful lot of territory.

Parks was doubly an outsider there. Born in Kansas, he’d lived in the Twin Cities, Chicago, Washington, D.C., and New York. A Mainer he was not. Parks was also Black. At the time of his visit, Maine had a Black population of less than one-tenth of 1 percent. Fewer Black people lived in the state in 1940 than had in 1840.

Yet often the more obviously someone is an outsider the more easily he or she might gain acceptance. Metaphorically, these photographs feel up close, not shot from a distance. Also, Parks was famously gregarious and engaging. Large as his talent was — he composed music and would later take up painting, become an acclaimed author, and direct films — his personality may have been even larger.

The exhibition includes a photograph of Parks with Brown, his wife, three daughters, stepdaughter, and granddaughter in the family home. The moment seems natural and unforced. Inevitably, the two men in the photograph register as white and Black. They could register just as well, and no less accurately, as two pipe smokers. Finding commonality came naturally to Parks.

John McKee, “Dawn, Popham Beach,”1965.Bowdoin College Museum of Art. Estate of John H. McKee.

John McKee, “Dawn, Popham Beach,”1965.Bowdoin College Museum of Art. Estate of John H. McKee.

John McKee (1936-2023) was differently an outsider: an Illinois native, educated at Dartmouth and Princeton. But after arriving at Bowdoin to teach French, in 1962, he stayed in Maine the rest of his life. McKee announced his newfound allegiance with “As Maine Goes,” a 1965 photo essay that makes up some two-thirds of the nearly 70 images in the current exhibition.

John McKee, “Scarborough Game Management Area,” 1965.Bowdoin College Museum of Art. Estate of John H. McKee

John McKee, “Scarborough Game Management Area,” 1965.Bowdoin College Museum of Art. Estate of John H. McKee

The photographs combine castigation and warning with a sense of saddened wonder. The beauty of coastal Maine is shown sullied by abandoned cars, billboards, drainage pipes, trespassing signs (all the more discordant for being nailed to trees). The fact that so much of what we see is otherwise so beautiful makes its sullying all the more grievous. McKee’s dismay, even disgust, is palpable. If Old Testament prophets had had cameras, McKee would have been Jeremiah.

The title plays off of an old political adage. Maine used to elect its governors in September. So the outcome of those elections was for many years seen to predict the vote in November: “As Maine goes, so goes the nation.” Political in a very different way, the implication of McKee’s title is clear, that the environmental depredation here is a warning for elsewhere. This was three years after publication of Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring” and the same year as passage of the Highway Beautification Act. McKee’s photographs were very much of the moment.

John McKee, “Linekin Neck,” 1965.Bowdoin College Museum of Art. Estate of John H. McKee

John McKee, “Linekin Neck,” 1965.Bowdoin College Museum of Art. Estate of John H. McKee

In addition to the 1965 Maine photos, there are later ones of the Sabbathday Lake Shaker Community and Japan (both chime with the chasteness of McKee’s own pared-down aesthetic), as well as France, Corsica, and Crete. In a nice tribute to McKee’s teaching career, a vitrine contains a reading list from one of his courses and a final exam.

Rudy Burckhardt (1914-1999) was that special combination of insider and outsider, the summer resident. A photographer and filmmaker, he lived most of the year in New York and had a home in Searsmont. He made these three short films in and around his house. “Daisy” (1966) is in black and white. “The Apple” (1967) and “The Caterpillar” (1973) are in color. They feel unmediated and look unemphatically beautiful — that is to say, they’re beautiful without calling attention to their beauty (harder to do than it sounds).

Still from Rudy Burckhardt, “The Apple,” 1967.Courtesy Jacob Burckhardt and Tom Burckhardt

Still from Rudy Burckhardt, “The Apple,” 1967.Courtesy Jacob Burckhardt and Tom Burckhardt

Each uses sound to excellent effect, but differently: a Schoenberg piano piece for “Daisy,” a song version of a Kenneth Koch poem for “The Apple,” birdsong for “The Caterpillar.” Both “Daisy” and “The Caterpillar” could accurately, but incompletely, be described as nature films: shots of clouds and trees and greenery and, of course, a daisy in one and caterpillar in the other. Shot in stop-motion, “The Apple” differs from them in offering a mini-narrative: The title item is ambulatory! Consider the possibilities. Burckhardt did, and happily so.

“Hello, Stranger: Artist as Subject in Photographic Portraits since 1900” is just what it subtitle says. The show closes Aug. 10. Unlike the others, it would seem to bear no relation to Maine.

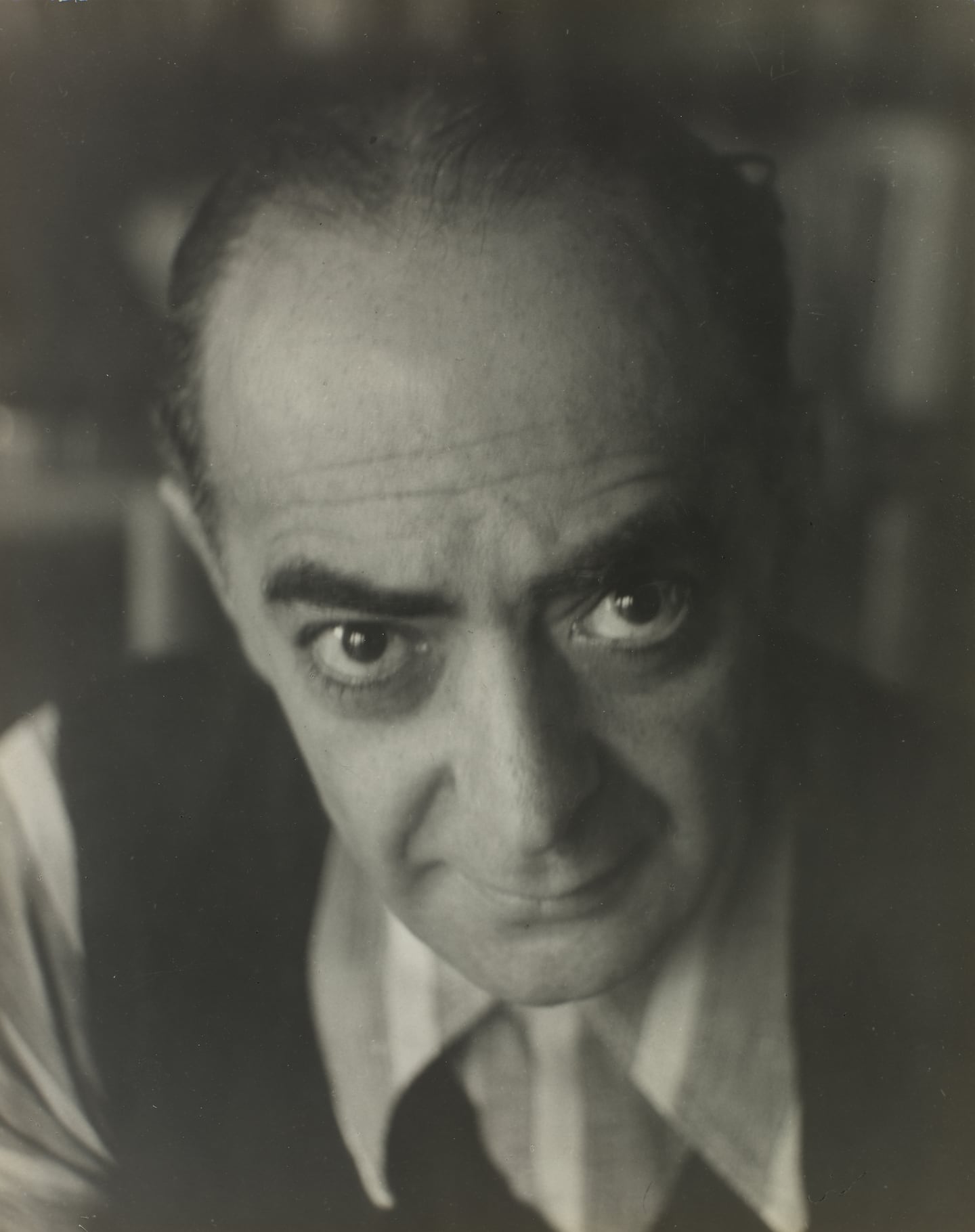

Israel Bidermanas, “Brassaï,” 1945.Bowdoin College Museum of Art

Israel Bidermanas, “Brassaï,” 1945.Bowdoin College Museum of Art

The show draws on a recent donation of 230 photographs to the museum. The temptation is to describe all of the 30+ photographs on display, they’re that eye-catching. Let three suffice.

A young David Hockney warily eyes Cecil Beaton’s camera. Brassaï looks a bit like his fellow Hungarian, Peter Lorre, in Israel Bidermanas’s 1945 portrait. In a very amusing six-photograph sequence, “I Build a Pyramid,” Duane Michals does just that, with some famous Egyptian ones in the background.

Wait, maybe that provides a Maine connection for the show. There’s an Egypt in Hancock County. So add international Maine to the list. As Maine goes, so goes the world.

GORDON PARKS: HERKLAS BROWN AND MAINE, 1944

JOHN McKEE: AS MAINE GOES

RUDY BURCKHARDT: Three Maine Films

HELLO, STRANGER: Artist as Subject in Photographic Portraits since 1900

At Bowdoin College Museum of Art, 255 Maine St., Brunswick, Maine, through Nov. 9 (“Hello, Stranger” through Aug. 10). 207-725-3275, bowdoin.edu/art-museum

Mark Feeney can be reached at mark.feeney@globe.com.