The saying goes: Never judge a book by its cover. But what about the edges of its pages?

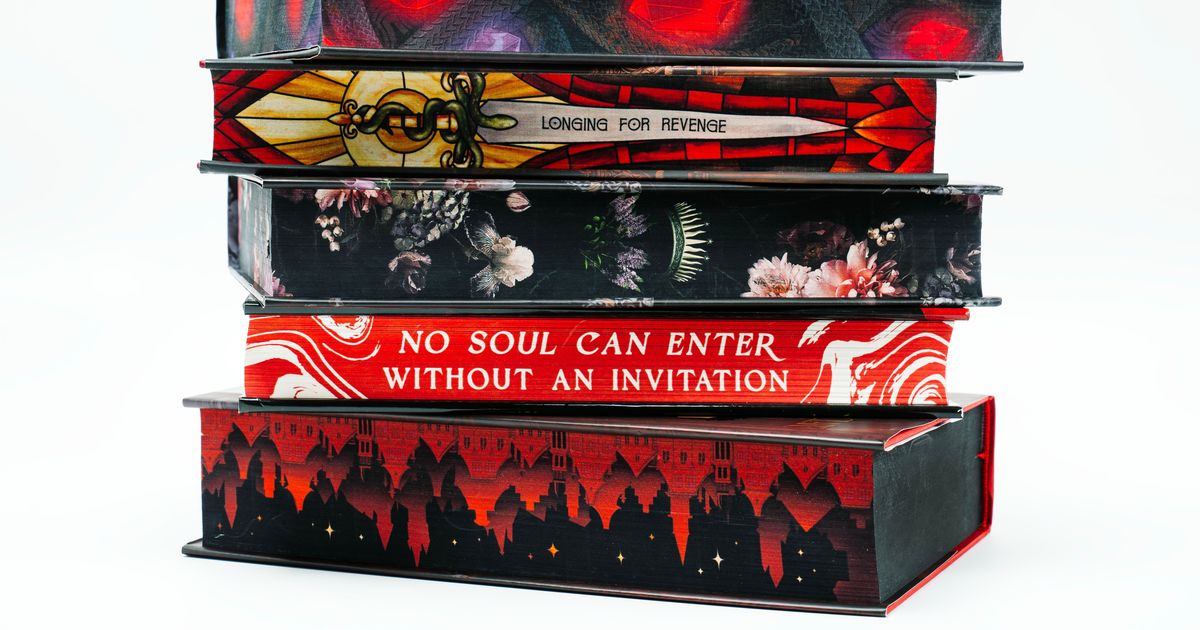

Sumptuous fore-edges – sprayed a bright color, stenciled with city skylines, made to look like pointy teeth – used to be relatively rare. But in recent years, publishers have brought decorated edges to the masses. Edge-painted books are now so widespread that you can find them at Walmart. The feature has spread from romance and fantasy to horror, thrillers and even literary fiction; it’s spread from works by famous authors with ravenous followings to those by debut novelists hoping to make a splash. It even has a (horrifying) portmanteau: spredges. On social media, readers show off floor-to-ceiling shelves crammed full of these books – spines facing inward, of course.

Jim Sorensen, president of Lakeside Book Co., the largest book manufacturer in North America, recalled the time a decade ago, when a colleague brought back edge-printing samples from a work trip to Europe. “Honestly, there wasn’t a whole lot of interest” from clients, Sorensen said. Times have changed: “We’re now producing millions and millions of books on an annual basis with this specialized edge design.” Since bringing in new equipment last year, the company has quadrupled its capacity for such projects.

The surge was driven by a few corners of the publishing world. S ubscription companies, such as LitJoy Crate and Illumicrate, seeded interest (and a sense of exclusivity) among readers as they printed relatively small runs that quickly sold out. Self-published authors, selling special editions of their books on their personal websites or at conventions, also helped to popularize the look. This prompted publishers to invest in the trend. When, in 2023, Bloom Books sprayed the pages of Elle Kennedy’s Off-Campus novels in powder blue, the set hit the bestseller lists – an unusual success for a collector’s bundle.

“People were excited for the new covers – but they were really excited for the edges,” Editorial Director Christa Désir said.

Barnes & Noble, after seeing the trend take off with the exclusive editions sold by its sister chain Waterstones, now devotes an entire section of its website to decorated, stenciled and sprayed edges. Decorated edges have “developed into an extension of the book experience itself,” said Shannon DeVito, director of books at Barnes & Noble.

The printed-edge craze has also opened up a new business niche. Inspired by DIY videos, Stephanie Moreno launched an edge-painting service earlier this year, including live painting at author events. What, after all, could be more limited than an edition only offered at a single local signing? “It’s a way to create excitement, bring people together, and give them a nice look that’s different for their book,” she said.

For designers, the edge gives a whole new surface to play with and another opportunity to make a book recognizable. “From a creative standpoint, it’s thrilling,” said Molly Waxman, executive director of marketing for adult fiction and nonfiction at Sourcebooks. Logistically, there were some kinks to work out, she added – such as building in time for ink to dry, so pages don’t curl unattractively.

As printed edges have flooded into stores, ramping up the competition for eyeballs, “the bigger race is being able to manage all of these specs and still hold a price point that’s not going to be so difficult for a consumer,” Désir said. “I’m not worried about us not having good edges. I’m more worried about: Can the book carry it? Is this something that’s going to sell enough that we can actually make it work at that price point?”

“Not every book needs edges,” DeVito said. Factors that publishers consider before spraying include genre and audience, and “what’s going to merchandise really well and stack well and draw your eye.”

For some, the novelty has worn off, with rumblings of complaint among some customers and booksellers. “Sprayed edges serve as a false flag of popularity,” Selah Jordan wrote in a recent article for Paste, complaining of books that smelled like fresh spray paint, many of them chipping in transit.

Anyone thrown for a loop by this trend can take solace in history. When, in the 1500s, people in the English-speaking world started storing their books upright and on shelves – moving them from chests and lecterns – they stored them just as many TikTokers do: with pages facing out. Title information was printed there in ink, said Mark Purcell, director for research and collections at Cambridge University’s libraries and archives.

Then, starting around the early 1600s in England, modish bookbinders started gilding titles on the spines of books, and so collectors started to reverse their displays. The practice spread gradually and unevenly over a century-and-a-half in what’s called “the Great Turnaround.” “It depends where you are, how up-to-date you are, how fashionable you are, how wealthy you are, what your library is like, all sorts of things,” Purcell said.

But wait, how did pages-out become standard way back in the first place? “I think you could just flip the question around,” Purcell said. “Why is it the convention that we store them with the spines out? There’s no reason – it’s just what you do.”

He did note one possible practical consideration favoring the old way: Some libraries threaded chains through their collections for security reasons, and the system only worked with the pages facing out. Publishers looking for the next big thing, take note.